AWOL on the Appalachian Trail (17 page)

Read AWOL on the Appalachian Trail Online

Authors: David Miller

At seven in the morning, a bunch of hung-over hikers are out of bed cleaning up after yesterday's wedding and reception. We spend about an hour picking up trash and packing folding chairs and tables. Even the hiker whose sleeping bag is out to dry is working. Bill heats up leftover potatoes, peppers, and bread for breakfast, along with much coffee. By nine o'clock most of us, sans packs, are headed for Harpers Ferry, twelve miles north.

I am so tired I sleepwalk through the miles. The grade is fairly level, rocky in places. Someone has assembled twigs to form a square frame on the trail. Inside the frame, pebbles are arranged to spell out the number "1,000." I've been hiking for one thousand miles.

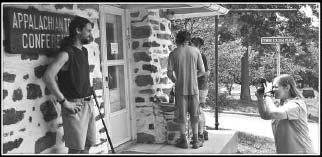

On the final stretch into town, I cross the Shenandoah River on the long, bending bridge of Highway 340. I am isolated from the cars by a concrete barrier, but I feel propelled by their breeze as they whip past, like I am on a victory lap. After crossing the bridge, the trail enters woods on the outskirts of town. I take a side trail that leaves the woods, crosses the grounds of Storer College, and leads to the headquarters of the Appalachian Trail Conference (ATC), a nonprofit organization that builds, protects, and manages the trail. A staff member is out front taking pictures of thru-hikers, using the building's facade as the backdrop. The ATC keeps a photo album for each year, with a photo and a blurb of information on every thru-hiker passing this point. I am the 528th thru-hiker this year.

Laurie Potteiger takes a picture of Awol in front of ATC headquarters in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia.

I hear "Awol!" yelled from down the street. Tim, my friend from Florida, is doing as the Romans do by using my trail name, yet it is odd to hear it from him. He is here with his parents, Dan and Wilma Kesecker. They take me back to their home in Martinsburg, West Virginia, twenty miles to the west.

I have only met Tim's parents on two occasions before this. They are exceedingly friendly and caring, the type of couple who seem like parents to us all. I am treated to a shower, a home-cooked dinner, and a comfortable bed. Tim talks about how projects have progressed since I left the workplace. There is much work to be done, and they are likely to be hiring in the fall, when I will be finished with my hike. He believes that the company will be willing to rehire me. I am content knowing that decision is still months away.

The day starts out great with Wilma Kesecker making me the bst pancakes I've ever had. The Keseckers return me to the ATC Headquarters building, and I take the blue-blazed trail out of town and back to the AT. The AT wiggles briefly through the woods overlooking the Shenandoah River, and then reenters Harpers Ferry on the north end of town. I cross the Potomac River on a wire-fence-enclosed footbridge. From the bridge, there is a view down to the convergence of the Potomac and Shenandoah Rivers. The merged river keeps the name Potomac and flows east through Washington, D.C., about fifty miles away.

The Potomac River is the northern border of West Virginia, so upon stepping off the footbridge, I start my sixth state on the trail, Maryland. The state begins with the easiest two and a half miles on the AT. This bit of trail is on the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Towpath. The towpath is a wide pathway of packed dirt, similar to a dirt road, but thankfully without tire ruts. The towpath and the shallow canal parallel to it were constructed as a trade route between Washington and towns in the Potomac Valley as far west as Cumberland, Maryland. A team of mules driven along the towpath pulled barges loaded with cargo. The towpath was last used commercially in 1924. Now, it is a 184-mile-long national park.

25

A hundred yards down the towpath, I turn to look back at the footbridge. There the Keseckers stand, waving goodbye. All the towns through which the trail passes are distinctive and inviting. When I hike in one day and out the next, as I have done here, it feels rushed. I would return to spend more time in Harpers Ferry--sooner than I could have imagined.

Thru-hiker Kodiak passes me on the climb up Weaverton Cliffs; we both stop a short distance later at the Ed Garvey Shelter, a fine new bi-level shelter. Kodiak started a thru-hike in 1999 but quit halfway through for lack of funds. He regrets not finishing the hike on his previous attempt and is determined to finish this time. This year he started the thru-hike with his wife, who decided to get off the trail at Harpers Ferry. This is his first day hiking without her, and he seems caught up in his thoughts.

The first half of the trail through Maryland is a nice stroll in the woods. The terrain is fairly smooth, and the grade is mild. Trees and undergrowth are pleasantly green, but not suffocating. When I arrive at Gathland State Park, a small, grassy park, I see enough sky to determine that rain is coming. There are soda machines at the park under a small overhang on the porch of the bathroom building. I huddle under the overhang with four other thru-hikers, getting our feet wet by the slanting rain. I buy a soda and, with it, eat all of the treats Wilma packed for me.

Dahlgren backpacker's campground is my stop for the night. There are restrooms with showers, picnic tables, and a tenting area large enough for at least a dozen tents. Kodiak, Ken and Marcia, and more than a handful of other thru-hikers are here. I fix and eat my meal at a table with Orbit, whose situation is similar to Kodiak's. Orbit was hiking with his girlfriend, who got off the trail yesterday.

Harpers Ferry is a major milestone. Thru-hikers consider it the halfway point, even though it is eighty miles short of the trail's midpoint. A number of hikers have chosen the Harpers Ferry milestone as a drop-out point. Ken tells me, much to my surprise, that Bigfoot is off the trail. Some hikers have taken time off to visit Washington, D.C., and still others, like No-Hear-Um, head up to Katahdin to walk the second half of the trail north to south. The rest of us continue north with our mood receding from the elation of making it this far. We a bit more serious, down to the business of focusing on the next goal. I always feel apprehensive when thru-hikers decide not to continue, particularly at this time of mass defections.

I am up and away early, opting to walk an hour to Washington Monument State Park before making breakfast. I cross over two walls made of stacked stone. This part of the country is rich with history, detailed by frequent plaques and monuments. Seeing these stone walls in the dewy, peaceful morning woods gives me a more visceral feel for history than any of the plaques. Civil War soldiers hunkered behind these walls as the opposing side approached. The harsh percussion of bullets on rock would be a devastating departure from the stillness of the woods. How could a man function from behind this explosion of splintering rock and smoky lead?

The original Washington Monument, built in 1827, is a sturdy stone building thirty feet tall, shaped like an upside-down drinking glass. I walk a staircase that spirals upward along the inside wall of the cylinder, exiting on the flat roof to see a grand view of the valley below. I descend from the park, back to the present, and cross Interstate 70 on a concrete pedestrian overpass. From the woods, north of the interstate, I look back to see Orbit crossing as a pair of eighteen-wheelers rumble underneath.

The rockiness of the trail increases as I progress, as if I am heading toward a great mound of rock from which these scatterings have been dispersed. Eventually, my feet no longer touch dirt, and I am stepping from rock to rock and weaving around boulders. I reach Ensign Cowell Shelter after fourteen miles that have seemed much longer. A small group is at the shelter, and Kodiak and Orbit arrive while I am snacking. Even though the rocks have worn us down, it is still early, and the three of us will likely move on.

"Do you think you will go all the way to Pen-Mar?" I ask Kodiak. Pen-Mar is a park on the border of Maryland and Pennsylvania.

"I might. Twenty-three miles...that would be a long day." Although Kodiak is a stronger hiker than I am, he hasn't been hiking days this long. He was hiking with his wife, and couples generally end their day when either person is ready to stop, resulting in shorter days.

"There's pizza," I add.

We know from the guidebook that there is a phone at the park and a pizza place close enough to deliver. Food is always a primary motivator. On the downside, there is no camping at or near the park. I continue on, with uncertain plans. Kodiak and Orbit will probably do the same. There are always miles to be walked.

The rocks abate for a few miles. A fifty-yard-wide swath is cut through the trees to make way for power lines that drape over the hills and extend out of sight. Huge four-legged metal giants stand in file, holding up the wires. The trail follows the clearing downhill, exposed to harsh sunlight and encroaching weeds.

The trail reenters the woods, and again rocks dominate the landscape. Earlier in the day, rock hopping was an interesting diversion. Now, having already hiked twenty miles, the rocks are an unwelcome challenge. The terrain is more difficult, with greater slope and rocks jutting up irregularly. This boulder field is significant enough to have a name: the Devil's Racecourse.

I am tired and distracted, plodding through the boulders. I recollect events of the day, as I am prone to do, when it occurs to me that I am in the midst of a protracted day. Visiting Washington Monument seemsonger ago than this morning.

The trail is going steadily downhill now, so I know I am nearing the end of the racecourse. Pen-Mar Park is only a couple of miles further. I take a lunging step down from a boulder about three feet high and land unevenly. All my weight, and the weight of my backpack, comes down on the outside of my right foot. I have rolled onto the outside of each foot a handful of times up to this point on my hike, but this time it turns a little further.

I fall and roll into a sitting position, my injured leg quivering. I know immediately that I have sprained my ankle. The feeling is not so much painful as it is numb, out of whack. I look around to see what went wrong. There is no outstanding irregularity on the ground that should have caused me to misstep. Maybe there was a rock that I landed on that kicked away after I stepped on it...no, my right foot must have nicked the boulder's surface on the way down, so that my shoe turned inward before landing. My hiking poles are lying free on the ground, but I can't even recall letting them loose.

I don't even want to look at my ankle. If I take my shoe off, I probably won't be able to get it back on. I take three Advil, stretch for my poles, and get to my feet. My best chance of walking is now--waiting will only make it harder.

I can put weight on my right foot, but I have to be careful about lifting and placing it. If the ground where I place my foot is uneven, I feel a tinge of pain. It is more painful to make the slightest bit of contact with a rock while lifting and moving my injured leg. This simple sequence of lifting my foot cleanly and finding a smooth place for it to land is a challenge among the jumble of rock.

Thoughts swirl though my head as I limp down the trail. I have some anger toward the trail for taking me through the minefield of rocks, and I'm disappointed in myself for getting tired and careless. Why couldn't I stay focused? Why did I have to push myself through another long day? Then I play through all the scenarios of what I might do next. I'm not eager for another extended motel stay like my recuperation in Wytheville. It would be wasteful to spend more time away from home, especially being less sure that I'll be able to continue hiking. Am I making it worse by walking on it? I need to get down to the park and take a look at my ankle before I can figure out what to do. Maybe it's not as bad as I think; I could camp tonight and hope it's better in the morning.

I hear Kodiak steaming down the trail behind me, so I pause to let him pass. As he approaches, he comments, "These rocks are a nightmare. Someone could really get hurt on this stuff."

"Yeah, I just sprained my ankle."

He continues on without pause or reply. What I just said didn't register, maybe because I stated it so simply and he had his headphones on. This is fine, since I prefer not to be escorted down the trail. There is nothing he could do to help.

At Pen-Mar Park, I get my shoe off and have a look. Disturbing, unnatural swelling has overtaken the outer knob of my ankle joint. Kodiak, still lingering at the park, offers his assessment of my ankle: "Oh, shit!" The look of my ankle eliminates any thought I may have harbored about walking through the injury, and increases my doubts about continuing at all. Perhaps I should be thinking of ways to get back home. I call Juli from a pay phone at the park. From home, she looks up where I am and tells me of the nearest hospital in Waynesboro, Pennsylvani

I also call Tim, who has already flown back to Florida. I wonder about returning to the Keseckers' home, but I'm too tentative about inviting myself to call them directly. Tim is encouraging, telling me that they would be thrilled to have company.

"The man at that house over there," a park ranger says, pointing to a home across the street from the park, "will give you a ride. He's taken hikers to town before."