AWOL on the Appalachian Trail (14 page)

Read AWOL on the Appalachian Trail Online

Authors: David Miller

"David, we'll be proud of you whatever you decide to do," Juli answers, thinking that I am considering getting off the trail.

I don't feel like quitting. Sometimes I want to be done faster; always I want it to hurt less. I haven't had any day that has been entirely bad, and I've yet to have a day when I wished I was back at my job.

The Appalachian Trail in Virginia is 535 miles long, roughly one quarter of the overall trail length, and longer than the trail through any other state. It is said that the trail in the state is easy, but that has not been my experience. I reached Damascus in less than a month, but my progress has sputtered since then. It is June 15, I've been in Virginia for twenty-two days, and I still have 156 miles to hike before leaving the state. Thru-hikers are so often worn down by this stage of the hike that there is a name for it: the "Virginia blues."

On the morning that Juli, Jessie, Rene, and Lynn are to fly home, we dawdle, using all the time they can spare before returning to the airport. I had been looking forward to their visit and had not contemplated the fact that I was setting myself up for another painful parting. They drop me off at featureless Bearwallow Gap, fittingly, in the rain. Before being engulfed by the woods, I look back to get a last look at my daughters. The view of them waving through departing car windows is reminiscent of them back in Georgia, but my attitude is entirely different. In Georgia, all was new and exciting and imprinted itself in my memory. Here, I am resuming the long walk through Virginia, and no detail of the trail, other than rain, makes an impression on me. On my first break of the day, I discover Juli and the girls have slipped drawings and notes of encouragement into my pack.

The water source for Cornelius Creek Shelter is a wide, shallow stream on the path leading to the shelter. While I pump-filter water, I take in the view. Sparkling water glosses over a bed of softball-sized rocks. The stream meanders among rhododendrons, and the pink flowers reflect off the water. Andy, Meredith, and Roman Around are at the shelter. I comment on the beautiful stream, and Andy tells me he sat by the stream for three hours before settling in to the shelter. Friends think I am free-spirited to have gone on this hike, but in that regard I don't compare with Andy and others, whom I observe to have much greater skill at the art of smelling the roses.

When I wake, I don't need to look at my watch to know it is 6:30 a.m., my habitual wake-up time on the trail. Rain is pinging the shelter roof--a sound known, but not loved, by hikers. All of us lie in our bags hoping for a break in the weather. A couple of hours later I grow impatient and hike out into incessant drenching rain and lingering fog. My camera stays tucked away, dead weight in my pack. There are few overlooks, anyway. The trail is never clear of trees, and there is heavy undergrowth. I resign myself to simply covering miles.

The miles don't come easily, with the trail climbing a number of peaks near or above four thousand feet, and descending all the way down to seven hundred feet at the James River, the lowest point on the trail so far. Before reaching the river, I stop to rest at Matts Creek Shelter. A hiker is in the shelter, asleep in his bag set on top of a two-inch-thick Therm-a-Rest. I've yet to see another thru-hiker with a sleep pad this luxurious.

The last entry in the register confirms what I suspect, that this is the thru-hiker who has been venting his unhappy experience in lengthy entries. I had yet to meet him, but I've heard other hikers comment on the melodrama of his hike, and I've read some of his writing. Here, he's taken the better part of two pages to record his misery and depression, clearly suffering the Virginia blues as much or more than the rest of us. He had come to this shelter last night in the rain. The shelter was full, so he spent a restless night trying to stay dry in the muddy crawl space below the shelter. He had decided to thru-hike after his last failed relationship. No longer a young man, he feels he has accomplished nothing of which to be proud. He had come to the trail to make something of himself. An AT thru-hike would give him "something to hang his hat on." Early on his hike, he met a young woman with whom he hoped to build a lasting relationship. Things aren't working out. The young woman is off hiking with someone else. His pack is too heavy, his feet aren't holding up, and every step is agony. Downtime has separated him from all other thru-hikers that he knows. He has nothing to look forward to on the trail, and has no life at home.

I imagine how I will recall these words a week from now, if he was to take a leap into the James River. I write a register entry of my own, sharing thoughts I've had about a thru-hike:

Anything that we consider to be an accomplishment takes effort to achieve. If it were easy, it would not be nearly as gratifying. What is hardship at the moment will add to our sense of achievement in the end.

By the time I'm done, unhappy hiker sticks his ruffled head out of his bag. After introductions, he asks if I've seen other thru-hikers recently, asking specifically about the hikers associated with the female hiker he has yet to give up on. In Daleville I had been told that the woman had jumped ahead on the trail to discourage his advances, so I avoid talking about her.

"I read about your foot pain. My feet are killing me, too," I say, addressing a problem to which I truly can relate. "This is the fourth pair of shoes that I tried."

"My boots are great. I've had them from the start. They're not the problem."

I take it that he's already been encouraged to try new shoes and he's having none of it. We talk a little about pack weight, and he only wants to tell me how much he likes and needs all the heavy stuff. He couldn't live without the mattress he's carrying. He moves on to other problems, equally insoluble.

"I just wish I could catch up to the guys I've been hiking with. I took days off trying to get better, and they are probably way ahead. It sucks being alone."

"Why don't you skip ahead and hike with them?" This really isn't a question. He's ready to ditch his thru-hike, so I'm trying to convey that it is okay to stay on the trail without walking every mile. Doing sections is a softer landing than just heading home.

"I don't want to skip. I want to thru-hike. I probably couldn't keep up with them anyway."

My most recent days have been a challenge. The positive attitude I project in my attempt to rouse him was only an act. I may have been of no help to him, but role-playing a better mood actually made

me

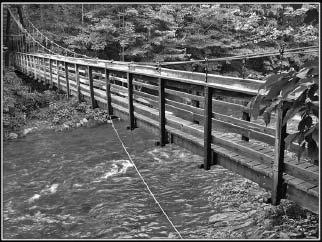

feel more upbeat. Also, the rain has stopped. I pack up and move ahead another four miles to Johns Hollow Shelter. The remainder of the walk is mild, traveling along the shoreline of the James River and crossing the river on a fantastic, long, and sturdy footbridge.

AA and Strider are at the shelter. The shelter is set in a flat-bottomed bowl of land at the foot of the mountains, a setting that helps me to understand the use of the word "hollow." Strider has a campfire going and uses it to cook his dinner. We all sit around the fire and talk of our experiences and plans, partaking in the simple pleasures of camping.

Strider started the trail with a purist mind-set, but soon joined with a group of hikers who are having a more social experience of the trail. He spent two weeks partying with them in Damascus. The group is ahead at Rockfish Gap, preparing to travel by canoe to Harpers Ferry, bypassing the trail through Shenandoah National Park. Strider is torn between going with them and hiking the entire trail. "I can still come back and hike the Shenandoahs later," he says, echoing a common refrainighheight="0%">

My morning begins with a two-thousand-foot climb in the rain. Same as yesterday, I am soaked before even walking a mile. Cold raindrops peck at my hands. I hunger for a protein bar, but my fingers are too numb to unzip my belt pouch. Everything is wet; I don't want to sit down. That would make me colder anyway. I am complacent about the struggles of the day. I am just making miles through the long, wet green tunnel. I knew there would be monotonous stretches. Hike on--that's the "solution" to which I keep coming back.

I was apathetic about planning when I left Daleville two days ago. Consequently, I am nearly out of food. Father-and-son section hikers are waiting for a ride where the trail crosses the Blue Ridge Parkway, making the sensible decision to cut their hike two days short to get out of the rain. I linger at the parking area where they are waiting, unloading trash from my pack and dropping hints about how I have used up all my food. They must have leftovers. Or maybe they'll give me a ride. They offer neither.

The trail runs along and over a number of large, scenic creeks leading down to the Lynchburg Reservoir, where there is a lake formed by Pedlar Dam. The trail crosses the lake on the dam, then inclines steadily up an unnamed peak on freshly cut trail with nice switchbacks. However, the ground here is smooth red clay, made slick by rain. Clay has embedded itself in the tread of my shoes, transforming them into muddy foot-long skis. On every upward step, I lose some of the ground I have gained to slippage. I walk duck-footed for better traction. I imagine I am entertainment for the trail gods, who have a boundless variety of obstacles to place before me.

Out of energy by the time the mudslide ends, I drift through the valley of Brown Mountain Creek, where there was once a settlement of freed slaves. All that remains is the detritus of a rock wall. I lie on the floor of the shelter by the creek, pondering my muddy legs, immobilized by indecision. Should I stay here tonight, or get into town and resupply? I am alone in the shelter, as I was on the trail today. Sluggishly, I drag myself on to the next road crossing.

A Boy Scout troop is at the roadside rest area when I reach U.S. 60. They look tired and restless waiting in the rain for their ride home. I move up the road far enough to dissociate myself from the group--lone hitchhikers fare better--and stick out my thumb. My destination, the town of Buena Vista, is nine miles away and is not a popular stop for hikers. And there is the drizzle of rain. Who wants a wet, smelly hiker in their car? Despite these factors, only a couple of cars pass before one stops to give me a ride. "Hey, look at that!" one of the Boy Scouts shouts, envious of my quick departure, as astonished as I am at my hitching good fortune.

In town, the motel clerk allows me to check out the "only" room they have available, a smoking room. A chubby white youth is strolling through the parking lot, wearing an oversized baby blue University of North Carolina basketball jersey and midshin-length shorts, the brim of his baseball cap turned sideways. I search for his parents, but there are no people or cars in the lot. "Want some weed?" he asks, using his best Eminem accent. I return to the office after surveying the room to say I can't handle the overwhelming smell of smoke. The clerk does a cursory shuffle of her reservations and says, "I can give you this room."

In the morning, the parking lot is still empty and there is a new clerk. "The lady who checked me in last night said all the nonsmoking rooms where booked, but it looks likf my quice are a bunch of empty rooms. Are most of the rooms smoking rooms?"

"No. She saw that you were a hiker, and most hikers smell worse than the smoke. We don't want them [hikers] to mess up our good rooms."

Trail angel William, a retired gentleman who has lived in Buena Vista all his life, gives me a ride back to the trail. The birds are chirping, the sun pokes through the clouds, my foot pain is short of agonizing, and I have a belly and pack full of food. This is a good day. There is a long climb, gaining two thousand feet in less than three miles up from the road, and I handle it easily. Jason, Shelton, and their dog, Mission, are atop Bald Knob. Clear skies on the open summit provide the first views I've had in days.

It starts raining when I am fifteen minutes from the shelter, and I make a dash for it rather than stop to put on my pack cover. No-Hear-Um and Leaf are at the shelter. No-Hear-Um is retired, but he is fit and I consider him to be a strong hiker. I've seen him sporadically since Kincora Hostel. He has decided to do a "flip-flop" hike. In Harpers Ferry, he will meet his wife and travel to the north end of the trail. From Katahdin, he will hike south, planning to finish his thru-hike at Harpers Ferry.

The AT progresses through Virginia with still more challenges. I hike up Priest Mountain, down to the Tye River (below one thousand feet), and back up peaks higher than four thousand feet. The terrain is rocky and, again, it rains. I don't leave the shelter until 9:00 a.m. to avoid a heavy morning rain.

Tye River Footbridge.

Gnats, flies, and black flies swarm me at every break on my walk over Three Ridges. Gnats fly into my eyes, nose, and mouth. Sunglasses fail to deter them. I eat three gnats; with effort, I could probably suck in a couple dozen. If all hikers consumed a few dozen gnats a day, would we put a dent in their numbers? Would they leave us alone if they feared us as predators?

It is getting dark because it is late and because another surge of rain is imminent. My guidebook tells me about landmarks I should pass every mile or so, and I'm not seeing them as soon as I think I should. I curse the landmarks for not being there and berate the guidebook for giving me erroneous information, but I know the fault is mine. I'm trudging along much slower than usual. I've walked over twenty miles. I am in the middle of a sixteen-mile stretch between shelters. My feet hurt and my legs are spent, and I need to find a place to camp. The trail is a narrow ribbon through waist-high undergrowth studded with rocks and tree roots. Even if the ground was clear, it would be too sloped to camp.