AWOL on the Appalachian Trail (28 page)

Read AWOL on the Appalachian Trail Online

Authors: David Miller

I backtrack as far as I can, still keeping the bears in sight. Once I am at a distance, the cub climbs down, and they continue on their way across the trail. A half mile later I see hikers headed south, and I warn them of the bears. "That's okay, I have pepper spray," one of them replies, yanking loose a canister that was strapped to his shoulder pad. They hasten forward like a hunting party.

Eight miles of the trail pass quickly, mostly downhill to Crawford Notch where U.S. Route 302 passes through the White Mountains. Starting back into the woods, the forest is darkened by the dense trees and humidified by a stream. It is one of those places that I feel should be inhabited by a moose, but I don't see one.

The trail is much steeper heading north from the notch. Trees block all wind, and I sweat heavily as I strain up the mountain. The trail seems to dead-end into a slab of bedk rising nearly vertical. I think I must be off the trail, but I look back and see a white blaze on a tree behind me. There is no way around. On closer inspection of the slab, there is a fissure that allows me to get foot- and handholds and make my way up fifteen feet to the top of the rock wall. I repeat this process of hand-over-hand climbing up short walls ten times on this single ascent. I am in disbelief that eighty-year-olds and at least one blind hiker have come this way.

My difficult climb is rewarded with a wonderful view from Webster Cliffs. From the rocky, open shelf of the cliff, I look south across the gulf of air between the mountain that I descended in the morning and the one I just climbed. Down below in Crawford Notch, at the nadir of the V between the mountains, runs the road that I crossed just one hour ago. There is a parking area and a pond, and barely discernible people move about. The word "notch" is used in place of "gap" or "valley" in the White Mountains, and the word seems more appropriate. Notch sounds more descriptive of these chasms between mountains, where a giant might get his foot wedged.

The trail turns toward the northern front of the cliffs, still on rocky ground with weather-stunted trees. The temperature has dropped, and I can feel my sweat evaporating rapidly in the gentle breeze. From Mount Jackson I can see an expansive view of the Presidential Range, the subset of the White Mountains between Crawford Notch and Pinkham Notch. On the horizon, Mount Washington looms so bulking that it blocks from view all that lies beyond. A blanket of trees covers the saddle of land between the peaks. Among the trees down and to my left there is a dot of white that is Mizpah Hut, two miles away, my destination for the night.

At the hut, Biscuit says, "I saw a moose just after the road. He was young and didn't seem scared of me. He stared right at me and wouldn't go away. Moose don't see well, so maybe he didn't know what I was. Did you see him?"

Biscuit is a student at Boston College. She is slender but strong, and I like that she has not attached herself to a group, as young thru-hikers are more prone to do. We are doing work-for-stay again, and she is a good companion. Our tasks for the night and morning are simply to set the tables for dinner and breakfast.

The morning weather is as good as I can hope for when I leave the hut and head for Mount Washington. It is just below sixty degrees, and the wind gusts are up to thirty miles per hour. This is calm for the Presidential Range. Less than a mile from Mizpah Hut, I go above tree line again as I ascend Mount Pierce. I will stay above tree line for the next twelve miles.

The terrain is a mix of rocks and matted blue-green vegetation. Rocky pinnacles jut up along the ridge. Fortunately, the trail weaves around, rather than over, the peaks of Mounts Eisenhower, Franklin, and Monroe. As I bend around the right of Mount Monroe, the Lakes of the Clouds Hut comes into view.

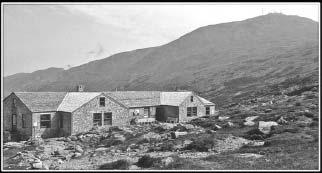

Lakes of the Clouds Hut and Mount Washington.

The hut is perfectly nestled in the saddle between Monroe and Washington. Lakes of the Clouds is the largest of the huts and is a simple, solid, ranch-style structure. The architecture of the hut blends beautifully with the landscape, complementing, rather than detracting from, the picturesque austerity of the mountain. The same cannot be said of the spindly collection of weather antennae on the ummit. From the northbound approach, Mount Washington rises to the right of the hut. The left shoulder forms a long, gradual slope. The cog railway, a steam-powered train that carries sightseers on a six-mile round trip ride to the top, travels along this slope.

A pair of southbound hikers, fit and young, are reading a pamphlet describing hikes on and around Mount Washington, noting the distances and time estimates for the walk from Lakes of the Clouds Hut to the summit. "Distance 1.5 miles, uphill one hour twenty-five minutes, downhill forty-five minutes," he scoffs. "We walked that in less than fifteen minutes, didn't we?" I note that neither has a watch. I am slow among these rocks. Even on the downhill, I lose time finding good foot placement. If I was to allow myself to speed downhill recklessly with the pull of gravity, I imagine I could manage a bit better than three miles per hour. The southbounder's claim puts their speed at a joglike six miles per hour, which would enable them to cover forty-eight miles per day, assuming they limit themselves to eight-hour hiking days.

Northbound hikers have heard such claims often enough to make inside jokes about time estimation. If we do many miles in a day, then we are hiking in "southbound time." To be fair, southbounders have undoubtedly heard the same exaggerations from northbounders.

The speed of the croo traveling between huts truly is amazing, and verifiable, since I have been passed by them. As I leave the hut, I see a long-legged croo member heading up Mount Washington ahead of me. I am determined to keep up, even though he's only carrying a day pack. He has a fifty-yard lead, and I cannot close the gap. His strides are longer, so I quicken my pace. I am not winded, but simply cannot place my feet fast enough. This side of the mountain is entirely composed of rocks, so there is no beaten path. The trail is vaguely defined by cairns.

35

I meander, drifting to rocks that offer the flattest foot landing surfaces. I look up at the ever more distant croo member, who moves in a direct li

ne, never seeming to shorten or extend his stride, letting his foot take hold wherever it lands.

I've lost sight of the hiker ahead and wonder why the trail has veered to the west of the summit. The trail is level now, as if circling the mountain. When will it turn back uphill? The view ahead clears, and I can see that the path is headed slightly downhill toward the track of the cog railroad. I am on the wrong trail. I cannot imagine how I got off the AT. There is no point on the path where I had any indecision about where I was going. I hadn't seen signs or noticed anything that hinted of a fork in the trail. I had taken a long look at the map last night back at Mizpah Hut. I know the AT descends from Washington near the cog railroad tracks, so I continue on, hoping to reconnect with the AT. The trail passes under the tracks, which are dripping with black soot. Shortly beyond the tracks, there is a marked trail intersection, where I learn that I have skirted the mountain on the West Side Trail. I head southbound on the AT, back to the summit of Mount Washington. I leave my pack at the intersection since I will be coming back down the same way. Getting myself lost causes me to miss four-tenths of the AT on the north side of the mountain. I walked that much extra on the West Side Trail, and I walk the north spur of the AT twice.

In addition to the cog railway, there is a road that delivers tourists to the summit of Mount Washington. For a fee, you can drive your car up the narrow, winding, car-sickness-inducing road and get a bumper sticker that says, "This car climbedt Washington." You have to stop at intervals on the way down to let your brakes cool. A handful of buildings are up here, including a weather observatory, a snack bar, and a gift shop. The whole scene seems oddly tranquil for a mountain known for extreme conditions.

"Mount Washington has a well-earned reputation as the most dangerous small mountain in the world," is just one of the warnings stated in AMC's White Mountain Guide. The wind exceeds hurricane force (75 mph) on more than one hundred days in an average year, and the highest surface wind speed ever recorded (231 mph) was taken at the weather observatory on the summit. There may be snowfall, even in the middle of the summer.

36

The weather can change suddenly, and there is an extreme difference between the weather on the mount

aintop and the weather in the valley four miles below. Over one hundred people have died on the mountain, mostly from hypothermia. Mount Washington is accessible and underestimated--factors that contribute to the death toll. It is not easy to understand how people can die on a mountain with a snack bar on top. The AMC guide doesn't mince words: "If you begin to experience difficulty from weather conditions, remember that the worst is yet to come, and turn back, without shame, before it is too late." The book goes on to suggest inexperienced hikers would be wise to get their experience elsewhere, and that most deaths are due to "the failure of robust but incautious hikers to realize that winterlike storms of incredible violence occur frequently, even during the summer months."

37

Biscuit is in the snack bar. I left before she did this morning, but she is here first because of my

diversion. When I arrived, I could see all the way down to Lakes of the Clouds. When I leave an hour later, thick clouds have blown in, and visibility is about thirty yards. The temperature has dropped fifteen degrees, and the wind is up to forty-five miles per hour, with some stronger gusts. The mountain is covered in a cold, damp fog. The howl of the wind makes it difficult to hear anyone more than an arm's length away. Despite warnings of the volatility and severity of the weather, the sudden change is a shock. Biscuit asks if we can hike together; I gladly accept.

On the plateau between Washington and Madison, I feel suspended, like walking on the canvas of a vast tent, whose poles form the mountain peaks. The ground is a jumble of suitcase-sized rocks, leopard-spotted with green lichen. Cairns look ghostly, shrouded by fog.

There are dozens of trails in the White Mountains. The length of the Appalachian Trail is comprised of segments of other trails. Today I have been on the Crawford Path Trail, the West Side Trail (though I wasn't supposed to be), and the Gulfside Trail. Signposts at trail intersections identify the choices, but "Appalachian Trail" is not always identified. A sign may point to the northbound Osgood Trail or westbound Gulf Trail, and we need to know which one is the AT. On some signs, hikers have helped by carving the AT symbol next to the right choice. This is the one section of the AT on which I would advise carrying maps. Unfortunately, I don't have any with me now. I do have Biscuit with me, and I am more confident in her directional choices than my own.

Our miles pass safely, and quickly, since we sustain a running conversation about Biscuit's time in India, books, and the Gulf War. Fog has lifted somewhat as we near the splendid sight of sanctuary, Madison Springs Hut, dwarfed by the pyramid of Mount Madison rising behind. We are doing work-for-stay again. I haven't seen another northbound thru-hiker since leaving Greenleaf Hut. Large, heavy wood tables and benches serve as dining tables at all the huts. At bedtime they are pushed to each side of the open dining area. I lay my sleeping bag underneath a table to avoid being stepped on in the darkness.

The sound of wind slapping into the hut rouses me from sleep in the middle of the night. The cold air penetrates the hut as if the walls are perforated. I sleep on the cold wood floor of the dining room, fully clothed and buried within my sleeping bag. I am fortunate to be housed in the hut; my tarp would stop much less of this cold wind. In the morning, I wake from a deep sleep to the sounds of the croo in the kitchen. Biscuit has already put away her sleeping gear. I hustle to get myself up before they start putting food on the table above me.

The hut croo does a skit during breakfast, a takeoff on

Star Wars

. The costume for the young man playing Princess Leia is a pair of bagels strapped to his head like earmuffs. Darth Vader has a colander for a helmet and wears a black graduation robe. "Come to the Dark Side, Luke. You won't have to pack out your trash."

"Well, it

is

kinda heavy..."

Also, a croo member reads the weather report from the Mount Washington Observatory. It is forty-two degrees, wind gusting up to sixty-six miles per hour, wind chill twenty-eight degrees, visibility one hundred feet. Biscuit and I agree that it's safer if we hike together, at least until we're over Mount Madison.

The trail heads directly up the rocky summit of Mount Madison, a pile of rocks that is tough enough to negotiate without steady forty-mile-per-hour winds. The air is crisp and cold, the wind growing stronger as we climb. Sparse clouds are in the sky, white and wispy, blowing past at surreal speed, like frames of time-lapse video. I wear every bit of clothing I have, including rain gear, and I still feel cold despite the exertion of hiking uphill. Two packless guests from the hut are ahead. They approach the summit crawling on all fours, unable to stand in the wind. Their jackets fill with wind and extend above their backs like parachutes. Near the peak the gusts are so strong I can't move safely, and so I stay put for a minute or more, bracing myself against the wind. When blown from behind, I lean into the boulders and crawl, following the example of the hikers before me.