AWOL on the Appalachian Trail (29 page)

Read AWOL on the Appalachian Trail Online

Authors: David Miller

Biscuit and Awol on the summit of Mount Madison.

After the summit, there are still a few miles of ridge above tree line. My hands are numb inside my gloves. The trail turns east and follows a long, narrow ridgeline on a gradual downhill slope. The wind, blowing strongly from our right, displaces me each time I lift a foot, yet I have to be careful to land on flat, stable rocks. It takes Biscuit and me three hours to travel three miles from Madison Hut. Biscuit's pack cover blows off her pack, saved by a cord snagging on her shoulder strap. She looks downwind, to the north where all the land we see is below us, and asks, "Where do you think that would have come down?"

"In Maine," I answer.

Below timberline, the weather warms quickly. Off come the jacket, long pants, and gloves. By the time we reach P do m Notch, I am in shorts and a T-shirt. Two hours ago the wind chill was below freezing. Pinkham Notch is a major trailhead on New Hampshire Route 16, about eleven miles from Gorham. AMC runs a resort at Pinkham Notch, and there is a large parking lot bustling with guests and day hikers. Arrow is here waiting for us; he takes me and Biscuit into Gorham.

We stay at the Barn Hostel, an inexpensive backpacker bunkroom adjacent to a bed and breakfast. The building is shaped like a barn, with real beds, not bunks. Twin beds and queen beds are lined up in the loft like a mattress showroom. There are at least a dozen thru-hikers. I recognize Spock, a thru-hiker I last saw in the Smokies. Spock and his wife had jumped up to Katahdin and started hiking south (flip-flopped). They were in the 100-Mile Wilderness when his wife took a frightening fall.

38

She sustained a laceration on her head and bruises everywhere. Spock said they were very fortunate to chance upon a ranger and get a ride out of the woods

. His wife had to end her thru-hike.

Completion of the Presidential Range is a significant milestone for me. I am celebrating with a day off in Gorham. Since the start of my hike, I have told people, "I am headed for Maine," and now I am on the doorstep of the final state. I feel like I'm on the home stretch, even though I still have more than three hundred miles to go, and many of them will be difficult. Arrow is in town again today, and he treats me to a lakeside grill of sausage, chicken, and corn on the cob at Jericho Lake just outside of town. Later, we go to see Glen Ellis Falls near Pinkham Notch. From there, we can see hikers traversing rock ledges on the way up Wildcat Mountain. That's where I go next.

Gorham reminds me of Hot Springs in that it is a town concentrated along Main Street. It is a tourist town, with more hotels and restaurants than would normally be supported by its meager resident population. Some stores and hotels have "Nous Parlons Francais" signs; we are only sixty miles from the Canadian border. There are gift shops with moose and bear sculptures on the lawns. High-peaked roofs, the six-foot-tall ice cream cone on the parlor, and the clock atop the red town hall stand out brilliantly against the vivid blue sky. Further in the distance, the White Mountains form a razor-sharp horizon. In the winter, the town fills with skiers. Now, in late August, hikers are everywhere.

On the streets I see Muktuk, a hiker I met in Erwin. He flip-flopped from Harpers Ferry and is getting off the trail after reaching Mount Washington. He is out of time and motivation and seems resigned to his decision to end it here. I recall the excited conversation Muktuk led back at Overmountain Shelter and am sad for how it contrasts with his somber mood today. Our time back then was analogous to college graduation; now we talk of retirement.

I think of what I am doing on the trail. What have I accomplished? My time on the trail has been fantastic, but there has been no epiphany. I've nearly used up my quota of time being Awol. I have to go back to the real world, earn a living, and support a family. I have no insight into how I can return and avoid the doldrums that brought me here.

Caratunk

When my father took us hiking as kids, I was lukewarm about the trips. Yeah, the mountains looked neat and all, but couldn't we just drive around and look at them? Why'd we have to walk for miles and camp for nights on end and eat such nasty food? My dad's idea of good trail food was mincemeat and Vienna sausages. I couldn't discern how my older brother Chris felt about our trips; he was the least expressive person in our family.

In 1981 Chris spent a couple of weeks hiking in Florida, and then he hitched up to Georgia and started hiking on the AT. When he reached Damascus, he decided he would continue hiking all the way to Maine. In that year, only 140 thru-hikes were recorded. Gear and the trail itself have changed since then, and Chris was an iconoclast even in his own time. He hiked with no shelter, no stove, and very little money.

I was in college when Chris thru-hiked. I was hankering to join the workforce and little attuned to his adventure. For the next twenty years, until meeting the retiree thru-hiker in the Smokies, I would think of thru-hiking as something that free-spirited young people like Chris do instead of going to college.

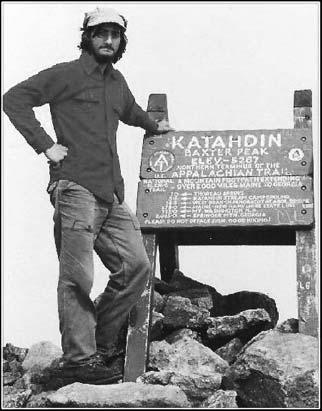

Chris Miller at the conclusion of his 1981 thru-hike.

When I was near thirty years old, I went for a short backpacking trip with Juli and a friend. It was even harder than I remembered from my trips as a child. I suffered from leg cramps; we got rained on and terrorized by lightning. We cut our trip short. I concluded that age had rendered me unsuitable for carrying a backpack for any significant distance.

Coincident with my inspiration by the retiree, I had been taking better care of my health, and I began to rethink my suitability for the trail. I'm tolerant of physical discomfort, I travel well, and I don't have to shower every day. I have a strong, slow, runner's heartbeat, even though I've never been a dedicated runner.

Upon deciding that I would thru-hike, I spoke with Chris. He contributed to my feeling that thru-hiking is best done alone, but he couldn't convince me to take on his minimalist style.

"I think I'll take a tent. They make them nowadays that only weigh three or four pounds," I said.

"How much do they weigh when they're wet?" Chris asked pointedly.

I get a late start from Gorham and worry about the long slack-pack that I am planning. Only a block down the road it rains hard enough for me to stop and put on my pack cover. Looking out to the mountains, the clouds collide with the peaks and twist into swirls of gray and white. I also decide to put on rain pants. It is an annoying task because I have to take my shoes off to put them on. My pack is falling apart; again the supports fall out of place and drop all the weight on my shoulders. Also, there are curved metal rods on each side of the pack that have worn loose from their cloth stays. The rods spin out of place and poke me in the rear. The pack spurs me like I'm carrying a little jockey.

The sum of my frustrations leads me to turn around and stay in Gorham for another day. I spend the day regrouping for the remainder of my hike. I find new rain pants with zippered legs, and I rig up my pack once mor>

Juli and I speak on the phone. She has had a difficult day, too. She has been working, mothering three kids, posting my journal, and sending me packages, along with all of the other household chores. "I'm ready for it to be over," she says, referring to my hike and the situation it has put her in.

Before leaving for my hike, I needed to know that Juli was committed to staying the course at home. It would not have been wise to take on the AT if she had given only a halfhearted "if that's what you want to do" acceptance. If that had been the case, she would be too inclined to reproach me while I was away. I could imagine a nearly tangible band stretching back home, tugging with more resistance as I headed north. Juli has been supportive, never wanting me to quit, and up until now, sparing me any guilt over making her life more challenging. She only tells me now, knowing that it cannot be construed as calling me back home.

When I had told one friend, a married woman, about my plans for a four- to five-month. AT thru-hike she said, "Good thing you're not married to me." She was right, but it was best not to tell her so.

Juli and I also finalize plans for the end of the hike. Juli, our daughters, and Juli's two brothers will fly to Maine on September 16. My timeline is now fixed. I have twenty-one days to hike 314 miles.

I leave Gorham after my second night in town, planning to return after my slack-pack today. The AT from Pinkham Notch to Wildcat Mountain is rigorous, often inclined steeply enough for me to lean forward and touch the trail with my hands. Even after hiking over eighteen hundred miles, I sometimes feel winded and my thighs burn a short way into an uphill climb. Usually it means I'm going too fast. I slow down, find my pace, and think about something else. Next thing I know, I've gone another hundred yards and I'm no longer struggling.

A group of hikers ahead are having difficulty with the climb. As I pass they make comments: "Look at him, just waltzing up the trail." Of course they are unaware of how I have to manage my own struggle. If a person who has not had enough exercise attempts to backpack, then he will find the going difficult. He might think, "I sweat, I get out of breath, I'm out of shape." But he is wrong to think the tribulation is uniquely his. Everyone sweats; everyone pants for breath. The person who is in better shape will usually push himself to hike more quickly and bump into the same limitations. But when the fit person is stressed, he is less likely to attribute the difficulty to his shortcomings. Backpacking is hard--that's just the way it is. Obviously conditioning is advantageous, but the perception of disadvantage can be more debilitating than actual disadvantage.

It takes me two hours to cover the first three miles and reach the top of the ridge. At this rate, I would finish at 10:00 p.m. The remaining ridge walk is rather saw-toothed, with each mountain on it having secondary peaks. Wildcat Mountain has summits A, B, C, D, and E. Carter Mountain has South, Middle and North summits. The trail goes over every one. At 3:20 p.m. I stop at Imp Campsite to get water after traveling thirteen miles without taking my pack off. This is the farthest I've walked without a pack-off break. I'm back on the trail in fifteen minutes, needing to hike eight more miles before sunset.

A note on the side of the trail warns that a "4,000-pound moose chased a hiker" near this spot; four thousand pounds is about three times the weight of a large mMido more than likely it was a fisherman who wrote the note. Moose tracks and droppings are everywhere. The AT is hemmed in by trees and underbrush. Occasionally a moose-trampled path cuts across the trail. Should an angry moose step onto the trail, there would be no easy exit.

The final four miles to Interstate 2 are easy and eventless, enabling me to reach the road before dark. I easily hitch a ride into town and spend my last night in New Hampshire.

I leave town in the morning and head down the road to find a good spot from which to hitchhike. A car pulls over to offer me a ride before I even stick out my thumb. The trail continues to be challenging. Much like yesterday, I have a long ascent to the ridgeline, and then I bounce over many summits along the ridge. Plateaus high on the ridge are sometimes muddy, even swampy enough for bog bridges. Most of the summits have open areas with exposed bedrock, trimmed with straggly krummholtz, low shrubbery, and some blueberry bushes.

As the trail descends from an unnamed hill, I can see Dream Lake through the trees. The lake is 2,650 feet high and completely encircled by the forest. Near the perimeter a few boulders poke through the rippled surface of the lake. From my vantage point thirty yards above the water, it looks like one of the boulders is moving. I stop to get a better look, my mind trying to reconcile the bizarre sight of a boulder moving about in the water. I'm considering the plausibility of a manatee or a seal being in the mountains of Maine when the head of a moose rises from the water. I ease my way down to the lakeshore, and the moose either doesn't see me or is unperturbed by my presence. She continues her routine, dipping her head to the lake bottom to feed, allowing her body to float so she can rotate.

Moose feeding in Dream Lake, Maine.

I meet up with Ken and Marcia at Gentian Pond Shelter and hike with them the rest of the day. We would stay on a similar schedule for the remainder of the trail. I've spent more time with them than with any other thru-hikers, and they are outstanding company. Ken is unflappably genial. Marcia is the more driven of the two; she is definitely not just tagging along with her spouse. Marcia is a reader, and we spend hours discussing books.

The last four miles of our day are difficult, with steep climbs and descents. Trail builders have erected log ladders to help us up or down some of the many rock ledges. Late in the day we come to a sign posted on a tree:

WELCOME TO MAINE

The way life should be

We arrive at Carlo Col Shelter after 7:00 p.m. It is cold and nearly dark. I cook and eat in the shelter with my legs in my sleeping bag.

I plan for a short day, less than ten miles, because today I will traverse some of the most difficult terrain on the AT. The morning is cold, below forty degrees, and windy as I head for the open summit of Goose Eye Mountain. I pass two southbound hikers and both have scraped knees. After Goose Eye Mountain, the trail descends to Mahoosuc Notch, a mile-long ravine reputed to be the hardest mile on the Appalachian Trail.

The notch is an alleyway between two steeply sloped mountainidges, filled with boulders that have tumbled down from the mountainsides. The boulders are huge; many are as big as cars, some as big as trailers. They lay hodge-podge at different angles with gaps between them. The white blazes, almost entirely on rocks, just give a general idea of the intended path. Each chooses his own path, deciding when to go over or around, left or right, at every impasse.

At the start of the section, I collapse my trekking poles and tuck them into my pack. I'll use my arms as much as my legs, pulling myself up and dipping myself down. I enjoy navigating the obstacles and the uniqueness of the experience. It is more of a physical challenge than an aerobic challenge, and it is a time-consuming process. Hikers generally take fifty minutes to two hours to traverse the notch. I try to stay atop the boulders, and with the weight of my pack I can lunge three or four feet across the gaps between boulders. When the crevasse is too wide or the boulders too uneven, I descend into the rubble and pick my way through smaller rocks.

Sometimes white arrows are painted funneling all hikers through the same slot. A few times this is done to put hikers through a squeeze below a gap in the boulders. Most hikers need to take their packs off and push them through the tunnel ahead. I am able to keep my snug internal frame pack on through the tunnels, but once I nearly get stuck as I belly crawl. Inside the last of the tunnels I find a water bottle that had been dislodged from the pack of a hiker before me.

As soon as the trail exits the Mahoosuc Notch, another challenging mile of trail begins. The AT heads steeply up Mahoosuc Arm, gaining fifteen hundred feet of elevation in the next mile. The surface of the trail is almost entirely rock, like a sloppily poured concrete coating. The "sidewalk" is the core of the mountain, exposed by hikers wearing away the soil. There is soil, duff, and spruce trees on either side of the trail. Walking is difficult on this hard, sloped surface. I am taking my time, eliminating the challenge by choosing not to fight the mountain. I climb slowly and stop often.