AWOL on the Appalachian Trail (32 page)

Read AWOL on the Appalachian Trail Online

Authors: David Miller

Section hiker 81 is on his way up Moxie Bald when I join him. From the stony flank of the mountain, we have views to other hills and to ponds below. The views are similar to those I had from Bigelow Mountain two days ago, yet the elevation is little more than half as high. There will not be another mountain anywhere close to four thousand feet until I reach Katahdin. 81 and I hike together to Moxie Bald Lean-to, two miles from the summit. Walking is pleasant on slightly sloped inclines, with open views to the ponds of Maine. The walk is not strenuous and we have breath to spare, so we talk the rest of the way to the shelter.

We are like-minded in our views about economics, and I find it easy to converse openly with him. My part of the conversation drifts into the financial implications of my hiking now, in midcareer. Before hiking, I hadn't really articulated my fiscal malaise. Talking it through with 81 helps me to sort out my own thoughts on the subject. My frustration over money matters contributed to my decision to take an extended hike. That rationale may seem convoluted since there is absolutely no financial upside to months of unemployment. But I had my reasons.

The period from 2000 to the time I started hiking in 2003 was difficult. The stock market bubble was deflating. The attacks on September 11, 2001, sent stocks even lower, gas prices higher, and made the future more uncertain than ever. Juli worked as a consultant in 2001. Since she had no employer to withhold taxes, I took additional withholding from my paycheck. It wasn't enough, and we were staggered when we filed our taxes at year's end. We owed an additional thirteen thousand dollars. The amount was unbelievable. We weren't rich. We had spent six child-raising years living off a single income, and we had hoped that Juli's return to work would allow us to put more money aside. The tax bill erased our savings; it was heartbreaking.

Taxes are by far the largest single expense in my life--more than cars or my house--at least double the expense of anything else. I'd spill my tax woes on others from whom I'd get no sympathy. They'd react as if it was my own fault. "You must earn a lot of money." Or, "You should have a big mortgage, find more deductions, learn about tax-free investments, have more withheld, etc." The first argument, "you earn too much," implies that striving for financial security is a sin worthy of punishment. The second set of suggestions reek of manipulation. I detest tax perks and penalties designed by the government to engineer our lives.

I succumbed to the least distasteful means of easing my tax burden. In 2002 I increased my 401K contribution and had even more money withheld for federal tax. On top of my tax woes, my twelve-year-old truck broke down, and I purchased a new vehicle using a loan against my 401K. I repaid the loan through yet another payroll deduction. Social Security, Medicare, and insurance were taken away from the remainder of my salary. For the

year

, my take-home pay was a mere 22 percent of my gross pay.

I was doing little better than breaking even; the compensation wasn't enough to keep me motivated. If I had been bringing home more, maybe I would've had a harder time walking away from my paycheck. As iWe owed at seemed feasible to go without a job for a while, to seek other rewards, to take ownership of my own time.

There is one other hiker at the Moxie Bald Lean-to, a previous thru-hiker named Dawn. She is filling in a small section of trail that she missed during her thru-hike. 81 and I undertake building a campfire. The ground is damp, and deadwood has been picked over by earlier shelter visitors. 81 has an abundance of matches, and we have a candle and strips of bark from plentiful birch trees. We get the fire to flame up, but it dies back down. I collect more birch bark, but again we do no more than torch the most flammable pieces. Dawn makes fun of us. We are two so-called outdoorsmen, with four thousand miles of backpacking between us, and we can't start a fire. Now that our pride is on the line, we scour far and wide to round up dry twigs. I also sacrifice a lump of toilet paper, slipping it into the pit while Dawn is not looking.

At twilight I walk down to Bald Mountain Pond, the water source for the shelter. The surface of the pond is flat and smooth, except for protruding boulders and reeds near the shoreline. I sit on a boulder with my water filter, hose dangling into the water, and pump water into my bottle. Back at the shelter I lie awake in my bag, perfectly content, whiffing the smoke from our sputtering fire. I can see the nearly full moon between the dark silhouettes of spruce trees, and its rippled reflection on the pond.

"Y'all missed it," 81 says (he's from Georgia). He was the first one awake and saw a moose near the shelter. I get up and go hunting with my camera, but the moose is gone.

I have eighteen miles to go before reaching Monson, the last trail town before Katahdin. The trail is nearly devoid of elevation gain and loss, but not without challenges. Thick tree roots lie like pythons across the trail. There are rocks to traverse. There are streams to cross: the Bald Mountain Stream, the Marble Brook, and the Piscataquis River. Some of them intersect with the trail in multiple places. None of the streams are bridged, but I am able to rock-hop across most of them. A larger variety of trees grow in this low-lying stretch of the trail. I walk through colorful stands of birch and maple trees.

In Monson, I find the largest group of northbound thru-hikers that I have seen since Gorham, including Ken and Marcia, Kiwi, Dreamwalker, Chief, and Jan Liteshoe. I met Chief and Jan back at Caratunk; Kiwi and Dreamwalker are new to me. All of us are electrified with the prospect of finishing the trail. It is all but over; 114 miles is like an afterthought in the scale of our journey.

Monson is about the size of Stratton, but there are no motels and no shops catering to tourists. Both restaurants on Main Street are closed. I visit the general store. It is no larger than a convenience store and peddles everything from food to clothes, drugs, cattle feed, and socket wrenches. Outside there is a pay phone, where I stand calling home at twilight. The sky is a brilliant purple, in its transition from blue to black, dark enough for the moon and stars to shine brightly in contrast. Trees and rooftops form a jagged horizon.

I stay at Shaw's Boarding House. Hungry Hiker is here; he is a young man I last saw in Virginia. He now has a head full of curly red hair and seems to have grown six inches taller. He finished his thru-hike over a week ago, with time to spare before his flight back to Israel, so he hiked south, back through the 100-Mile Wilderness. Hungry Hiker is a voracious eater. Pat Shaw's breakfast choices are "1-around," "2-around," "3-around," and so forth. Hungry Hiker has the 4-around, which means four blueberry pancakes, four eggs, four sausage links, four slices of ham, and four pieces of bacon, along with hash browns, coffee, and juice. Meals are served family style; all of us come to the table together. Ten hikers sit at one long table in the eat-in kitchen, and five more take seats at an overflow table on the porch. Hungry Hiker had Shaw's big breakfast yesterday, and he advises me to get only the 3-around. It is bad advice because it leaves me feeling hungry. Fortunately, Pat brings out a plate full of doughnuts. My typical trail breakfast is three packets of instant oatmeal and hot chocolate. Shaw's breakfast is far better. With meals like this, I've been able to maintain the same weight (about 160) since the middle of the AT.

Keith Shaw Jr., the son of the owners, will give Kiwi and me a ride back to the trail. Kiwi is a nimble sixty-one-year-old thru-hiker from New Zealand. He and his hiking partner, Dreamwalker, say their farewells. Kiwi needs to conclude his hike before his six-month visa expires, and Dreamwalker is staying in town a few extra days to meet family. For most of their hike, they had hiked in a group of four gentlemen roughly the same age, and the group was dubbed "The Four Geezers." Along the way, two fell behind. Dreamwalker and Kiwi hiked together all the way to Monson, but now have to part ways, a week away from finishing.

While we are loading the truck, a man from the house next door begins a bike ride with his two kids. The younger child is on a bike with training wheels; the older one is a girl about ten years old, similar in age to my oldest daughter. As they pull onto the road, the young one is having difficulty and falls behind. Dad looks back to see what is wrong and veers slightly toward his daughter. The daughter overreacts and jackknifes her front tire. She puts her hand out to catch herself, and the bike's handlebar falls across her arm, breaking her forearm near her petite wrist. She gets up confused and scared, holding her limp arm and calling for her father, "Dad, Dad...DAD!"

The event is troubling. I wish I could have done something; I wish kids never got hurt. They seem too tender to have to deal with pain. I take solace in believing that her initial shock and worry was the worst of it. By tonight, she'll be home eating ice cream and having friends sign her cast.

Keith Shaw drops us off at the trailhead, and we enter the 100-Mile Wilderness. From here to the base of Katahdin there is little access to civilization. The trail will cross a few logging roads, but hitches from these are improbable. A group of three young southbound hikers stop to greet me and Kiwi.

"Congratulations," they say. It is common for southbound hikers to congratulate us on the completion of our thru-hike, even now, far from Katahdin. One of the hikers looks familiar. It is Peter, the first thru-hiker I met on my journey. Back in Georgia he was a pale and timid kid; now he has filled out. He is bearded, with shaggier hair and much more confidence. We both recognize each other from a single two-minute trail passing 137 days ago. He flip-flopped and will finish his hike southbound. Just from the brief glimpse I have of his demeanor, I like the impact the trail has made on Peter.

Kiwi and I exchange equally uncertain plans for the remainder of our hike. I have a pretty good idea of where I will be each day, and I'm sure Kiwi does as well. Hiker etiquette necessitates vagueness in how you divulge your plans. If you find the new acquaintance disagreeable, you can deviate from your actual plan without effrontery. If you change plans for other reasons, you won't unintentionally offend hikers you really aren't trying to avoid.

In our walking and talking, the beauty of the scenery has not escaped me. There are still ponds, rocky summits, streams, and a variety of trees and brush. I linger at Little Wilson Falls. The falls cascade over a stepped rock wall with such uniform geometry that it looks man-made. I take a side trail to get better photo angles. By now I have concluded that Kiwi is in no way offensive--actually, he is very likable, and his pace is well matched to my own. Still, I think of my photo shoot as an opportunity for us to gracefully go our separate ways.

The next section of my walk is tiring. There is small elevation gain and loss, but little completely level ground. Continual change from uphill to downhill--roller coastering--is often more exasperating than extended climbs or descents. I push on without pause, wondering why I haven't caught up to Kiwi. I imagine the old guy ambling along while I struggle. When I arrive at Long Pond Stream Lean-to, Kiwi is there resting comfortably, looking as though he might be staying. I have my sights set on the Cloud Pond Lean-to four miles further. After a short break, I put my pack back on and notice that Kiwi does too. It occurs to me that Kiwi's vagueness of plan had a purpose I had not foreseen. I believe he did not pin himself to a specific schedule so that we might tacitly adapt to each other's plan. Kiwi has hiked with one or more partners for over two thousand miles; it is as natural for him to have a partner as it is for me to be alone.

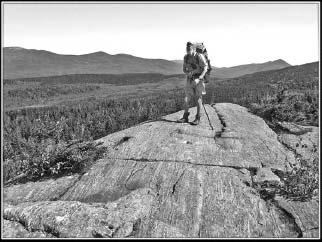

The remainder of our day is all uphill, with a steep climb up Barren Mountain. Halfway through the climb, we pick our way up through a rockslide, culminating in a rocky ledge. We stand on house-sized boulders that elevate us above the trees, from where we have dazzling views of the Maine countryside. There are the omnipresent ponds and the gentle contour of low hills carpeted with dense green trees.

Kiwi on the Barren Ledges.