AWOL on the Appalachian Trail (26 page)

Read AWOL on the Appalachian Trail Online

Authors: David Miller

The trail briefly runs tangent to Little Rock Pond. I am sluggish, so maybe the cold water will wake me up. I strip and jump in. Only feet from the trail, I'm risking an audience, but no one passes. The water is refreshing, but the rocky bottom of the pond is torture on my tender feet. My feet hurt when I walk barefoot, even on smooth ground. The rain has been hard on my feet. They are soggy and wrinkled, and sloughing dead skin from calluses. I have another cracked toenail--it will be the sixth one I've lost--and it is in the painful stage of working itself loose.

Six miles further, I sit for a break at a parking area that is empty but for one car. Two people are waiting at the car. The shelter-rating couple arrives, and they are relatively mud-free. Apparently they've escaped my vexing. The car couple has brought lunch, and the four of them pull out coolers and set up a picnic. They don't offer me a thing, not even a word.

It is raining and my toe is throbbing when I reach Clarendon Road. I walk west on the road a half mile and eat at the Whistle Stop restaurant, a small diner built into a train car. Further down the road, I visit a convenience store to get food to take with me. When I leave, I see thru-hiker Rain Crow in his truck. We've crossed paths on the trail a couple of times, and now I get an explanation of why I've twice seen him hiking southbound. Rain Crow will leave his truck at a trailhead, and hitch or catch a bus to another location on the trail a few days away. He hikes back to his truck and repeats the process. He will hike either north or south on each segment, whichever is more convenient, but overall his progress is northbound. Rain Crow offers to drive me around, looking for a place to stay. We pull up to a dilapidated motel with a gravel driveway and parking area. Ragged curtains blow behind the open jalousie windows. The rooms have no phones or air conditioning, so I am not enticed to stay. Rain Crow delivers me back to the trail.

With the rain stopped and with my hunger sated, I climb easily up to Clarendon Shelter. It is a leaky, broken-down shelter with a patchwork of repairs. String crisscrosses the front of the shelter, making an improvised clothesline. The line has more clothes than I've ever seen hung in a shelter. It's so weighted with wet clothes it impedes access. At a glance I count eight pairs of socks, and yet only one section hiker is in the shelter. "They all belong to those people," the hiker says, pointing to a tent twenty yards away. He tells me that there is a man and a woman, but they remain tent-bound during my stay and I never see them.

The next shelter I pass is the Governor Clement Shelter, a grubby, deep, dark shelter circled by tire tracks. There is trash in the fireplace, and offensive graffiti litters the walls. Shelters as a whole have been better than I anticipated. Collectively, AT shelters are my provisional home; to see any of them vandalized is disturbing.

I am much stronger today than yesterday. Some days I have more energy than others, with little correlation to sleep, diet, or conditions on the trail. I have not been sick on my hike. I haven't had a cold, or even a headache or upset stomach. My vigor is timely, for there is a climb of twenty-five hundred feet from Governor Clement Shelter to the top of Killington Peak. There are some rocky clearances on the south face of the mountain, and I can glimpse a view of the mountain range through the partially overcast skies. If there have been other overlooks in Vermont, I cannot recall; they would have been clouded over. There is intermittent rainfall again today.

My shoes are caked in mud, so I switch to camp shoes as soon as I reach Interstate 4. I don't want potential rides to pass me up for fear that I will track mud into their car. I intend to buy new shoes in the town of Rutland. My muddy, smelly shoes are falling apart. Still, I regret parting with them. These are the shoes that I purchased back in West Virginia that may have saved my hike. It is impossible to know if I would have continued this far dealing with the foot pain I had before switching to these shoes.

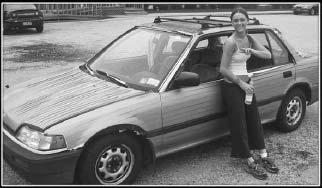

I get a ride from Carrie, a gregarious twenty-year-old with a beat-up, muffler-dragging car. As we drive I stare at the hood in front of me, at the curious silver-gray color. The paint looks almost like it is pin-striped, but some of the "stripes" are flapping in the wind. Carrie explains. "I took it in for the inspection, and they failed it 'cause they said there was too much rust. I can't pay for a paint job. So I...me and my friend...we bought some duct tape and we taped it up bumper-to-bumper. Every inch of it. I took it back and it passed."

Carrie and her duct-taped car.

Carrie takes me to the post office, outfitter, and a shoe store. Upon leaving each location she asks, "Where do you want to go now?" She would have chauffeured me around more, but I didn't want to abuse her generosity. We part ways at the shoe store, where I buy my sixth and final pair of shoes. I walk to a nearby motel to stay for the night.

Rain is the dominant feature of my passage through Vermont. It has rained every day, but there have been few strong rains. Trees accumulate light precipitation and then drip on me. Today is again gray and humid. Every rock, branch, and leaf is drenched, as if the earth was dunked in a giant tub. Anywhere that the ground is level there is mud or standing water. Streams that cross the trail overflow and course down the footpath. One stream is swollen to a width of six feet, too wide to jump over, and inordinately deep. After failing to find a crossing, I wade through, surprised to have the gushing water rise nearly to my kneecps.

The open ground in front of Stony Brook Shelter is pockmarked with puddles. A crowd of hikers is here; ten of us are in a shelter that would comfortably sleep six. Still more are tenting nearby. Eight hikers sleep packed side by side, conventionally arranged in the shelter with their feet toward the opening and their heads to the back. Since this shelter platform is slightly oversized, there is about eighteen inches of platform remaining at their feet. The last two hikers to arrive (Siesta and me) sleep clinging to this sliver of leftover space perpendicular to the other hikers.

These days on the muddy trail are little fun. I am just moving north while waiting for better days, reminiscent of the rainy days I trudged through in Virginia. Rainfall is heavy in the early afternoon. I welcome this decisive rain, taking it as a sign that this dreary front is finally pushing through. By the end of the day, the skies clear.

I approach a large but unnamed stream where a hiker is getting water, his pack leaning on a tree nearby. I've not seen him before, and without introduction he exclaims, "There he is! Can I get a picture?" I wait while he gets his camera and snaps my photo. "I'm Goggles. Surprised to see you here--you're going to make it!" Goggles is thru-hiking southbound. He used to live in the same county where I now live, and friends he left behind have been sending him my newspaper articles. In the last article he received, I had written about my sprained ankle.

The Rosewood Inn is my intended destination today, but when I arrive I find that the inn has been closed. I have already hiked seventeen miles, but I decide to push on for another nine to West Hartford. None of the days I have remaining will be this long. Goggles had told me that there is no lodging in town, but some families will take in thru-hikers. He stayed in someone's home, but I did not ask for details because at the time I did not plan to stop in West Hartford. I arrive after 7:00 p.m., exhausted. The only store is closed, so I wander down the street and talk to the first person I see. It is Kevin Kemmy, and when I ask him where I might stay, he replies, "You can pitch your tent in my yard."

"I don't have a tent." This is no lie. My tarp is at home; Juli is making modifications to it. My tarp hovers six inches off the ground, so it is not mosquito-proof. Juli visited during the peak of the buggy season, when I was intent on having this defect of my tarp corrected. I sent my tarp home with her and asked her to sew a skirt of netting around the perimeter. Mosquitoes have already become scarce. By the time she mails the modified tarp back to me (in Glencliff, New Hampshire), mosquitoes will no longer be a problem. Meanwhile, I have to use shelters, hostels, hotels, or sleep outside uncovered. The last option is particularly unappealing with the recent abundance of rain. In trying to fix a problem that went away on its own, I created a new situation to deal with. I should run for office.

Kevin bails me out. "Well, then, come and stay in the basement."

The only store I see in West Hartford is a convenience store with a gas pump outront. This morning the two cars parked at the store have "Take Vermont Back" bumper stickers. Inside, there are only two aisles, packed with everything people buy in convenience stores, only with less variety. In the back corner, there is an L-shaped counter with six barstools, and beyond the counter, the store clerk is doing double duty as a short-order cook. It is here that I have breakfast with four locals--thoroughly blue collar, big, weather-beaten men who leave none of their barstool seats unused.

Ten trail miles away is the Ivy League campus of Dartmouth College. In between here and there I walk through a peaceful, rolling forest of hemlock and white birch. A southbound hiker ambles by humming a tune, not missing a note as we pass.

I ease out of the woods onto a quiet residential street. Homes are nicely tucked away among the trees. This is the start of a three-mile road walk on the AT through the adjacent towns of Norwich, Vermont, and Hanover, New Hampshire. The towns and states are separated by the Connecticut River. I cross the river on a stately, four-lane bridge with "VT. | N.H." etched on a pillar in the middle. Passing over the bridge, I feel like I am entering a portal. My enthusiasm builds. Beyond this gateway are the final two states, which for the moment I imagine to be a lofty, remote, mountainous Shangri-la.

Hanover is a busy town. Bars and restaurants and ice cream shops and bookstores are bunched up close to campus. There are stores selling hats and green and white T-shirts that proudly and simply proclaim "DARTMOUTH." People fill the street, walking between shops; students tote books between classes and play hacky sack on the sidewalk. The wealth of the town is reflected in the architecture and upkeep of the area--and in the lack of affordable lodging. Still, thanks to the college kids, it is a place where a grungy hiker can feel comfortable. Most students still live on a budget, park on lawns, paint artwork on walls, play loud music, and hang banners from windows.

In the past, hikers were allowed to stay in fraternity houses on campus, but word on the trail is that the houses are now turning away hikers. On a tip, I try the Phi Tao house and get lucky. I am greeted by John, who shows me around the house and tells me the rules. There is a long list of them: no using the kitchen or laundry, no shoes indoors, shower only on the second floor, and sleep only on the floor in the basement. I don't mind; being allowed to stay for free is extremely hospitable.

"I thru-hiked last year," John tells me.

I know he has made the statement to put me at ease after presenting all the restrictions. "That's great," is all I can summon in reply.

John must have interpreted my simple response as skepticism, since he quickly adds, "I've gained sixty-five pounds since finishing the trail."

I truly am not skeptical of him completing the trail. He is a big guy, but I have seen plenty of overweight hikers stick with it and plenty of well-conditioned people quit. I have been considering how to transform my atrocious eating habits on my return to the real world. If I keep eating like I do, I will put weight back on faster than I lost it. I should ramp down my eating before I even finish the trail--but not yet. I walk down to the campus co-op grocery and bask in the wonderful display of food. The store is promoting corn by cooking it on a grill outside and giving it away to customers. I sneak in line twice to get two servings. I take home trail food and a box of eight doughnuts for breakfast, but I eat fouof them on my walk back to the house.

The centerpiece of campus is Dartmouth Green, an expansive lawn with the library tower and clock as a backdrop. There are obligatory ivy-covered brick buildings, churches, and a contemporary student center. All the buildings have a style befitting the campus, yet they are not uniform. Some are brick, some are slate, some are sandstone, and some are whitewashed, but all are pleasing to the eye. Since there is no laundry in Phi Tao, I walk over to another set of dormitories. I chat with two girls, follow them into their dormitory, and find laundry machines down in the basement.

Arrow, the 2002 thru-hiker I met before the start of my hike, had told me that he makes many weekend trips to the trail in New Hampshire. I give him a call, and we arrange to meet at lunchtime the day after tomorrow. It gives me no pause to plan on walking thirty-six miles in a day and a half.

In the morning, I follow the trail across the town of Hanover, past the bookstores, past Dartmouth's football field, past the co-op grocery store, and back up into the hills alongside the ball fields.

For miles, the forest is dense with hemlocks and birch trees. Under cover of the trees, it is dark and damp, a breeding ground for mushrooms. They are as small as a pencil eraser and as big as a saucer. Most have the typical mushroom dome, but some are flat-topped; one is shaped like a funnel, and some are shaped like coral (and are predictably named coral mushrooms). I see mushrooms that are white, red, orange, yellow, blue, and purple. The more I eat, the more colorful they are.

The trail meanders over this fecund soil for twenty miles, with soft hills and valleys ranging between elevations of eight hundred and twenty-three hundred feet. After crossing Lyme-Dorchester Road, the trail takes on a different look. The terrain is higher and drier, and the mushrooms are replaced by rocks, hills by mountains. From the vantage point of a rocky ledge, I can see a mountain rising up ahead, slightly off to my right. The mountain is completely forested, but still a fire tower is visible above the trees at the summit. The fire tower identifies the peak as Smarts Mountain, my destination for the night.

I know from my guidebook, my watch, and dead reckoning that I am a little more than a mile from the tower. The path is predictable; I will dip into a saddle between here and Smarts Mountain, and then turn right and climb uphill on the ridge that I now see in profile.

Geometry adds to the allure of hiking. On the AT I never feel like I am traveling on a straight line. I weave through boulders, sweep along a side-hill curve, spiral around a mountain, roller coaster up and down, skirt along the precipice of a cliff, pass through a narrow gorge. There are limitless physical configurations, ever-changing, inviting me to walk, pulling me forward to feel myself traverse the arc of the trail through the transitions, navigate the obstacles, fight gravity in a climb, or ride the pitch downhill.

Locations are engraved in my memory with positional attributes based more on my own internal sense of direction than on any objective reference point. I think of the trail veering to the left or of myself being on the right side of a mountain when "left" and "right" could be north, south, east, or west. My mind's eye sees shelters I have visited from a chosen perspective, regardless of their actual orientation relative to the trail.

I have been on the trail for twelve hours, covering 23.4 miles. It is dark and I am too tired to cook, so I have a dinner ocandy bars that John gave me when I left Phi Tao.

On top of Smarts Mountain, my shelter is a rickety fire warden's cabin, no longer in use, next to the fire tower. Viking, from Germany, is the only other hiker here. I chase a mouse off the doorstep as I enter. A broken window is covered with a plastic sheet. The plastic sheet is foggy and spotted with age, but the silhouette of a mouse climbing on the window sill is discernible. When I hang my food bag, I see a mouse peering down from the rafters. "For me?" he asks.

Between the cabin and my meeting point with Arrow at Atwell Hill Road, I cover twelve scenic and challenging miles. Climbs up Eastman Cliffs and Mount Cube are notable for the transition to rocky ground and scrub pines. Arrow has brought two friends, Wakapak and Giggler. They all did thru-hikes in 2002. They have brought a propane grill, a cooler, and an assortment of snacks. A gathering forms around Arrow's van to take in the burgers, chips, sodas, and beer. Northbounders and southbounders are here in roughly equal numbers. Northbounders, myself included, are eager to hear about the White Mountains. We solicit information from last year's thru-hikers and from southbound hikers who just exited the range.

The Appalachian Mountain Club (AMC) runs bunkhouses called "huts" in the White Mountains. They are large cabins that can sleep forty to ninety paying guests and have no road access. All guests have to hike in to the huts. The huts generate their own power from wind, solar, or hydro-electric generators. Each has a staff of about six that is responsible for cooking, cleaning, entertaining guests, and packing in supplies. The first few thru-hikers to arrive at a hut can do work-for-stay, and they cannot stay for more than one night. In exchange for menial tasks like setting tables and washing dishes, hikers are fed leftovers for dinner and breakfast, and sleep on the dining room floor.

One of the southbounders tells of his pass through the White Mountains. Work-for-stay at the AMC huts is such a generous deal that he stopped at every hut. Some days were short. For example, the distance from Mizpah Hut to Lakes of the Clouds Hut is less than five miles. He is fit, muscled, and proud of himself for slowing his pace in order to fully exploit the thru-hiker benefit. Is it a virtue to maximize your consumption of goodwill? It should be taken as it comes, rather than pursued. The southbounder is seemingly unaware that his indulgence likely deprives other hikers of this limited provision. Most huts only take in the first two thru-hikers. Hikers arriving after walking their normal day would be shut out by the southbounder who scampered between huts.

The southbound hikers experienced cloudy, drizzling weather through the Whites. I never visualized these treeless peaks with anything other than the blue sky that I've seen in pictures. I've been foolishly dreamy about where I am headed, and I swing toward pessimism. Of course I could get rain in the Whites. Odds are I will, considering my AT experience to date.

In fact, dark clouds materialize as I rouse myself back to the trail. Arrow and friends pack up the van. I will meet them again at the next road crossing at Glencliff, eight miles north. Arrow assures me that it is an easy walk. I don't think I will mind getting wet. After being on the trail for only minutes, the rain comes. I don't bother with any rain-wear, and I had covered my pack before leaving. The rain quickly intensifies into a storm. Cold, heavy drops of rain pound on me, and furious bolts of lightning crash down among the trees. I feel exposed. I

should

be struck, since my water-filled body would be an excellet conductor to bridge the bolts from the sky to the ground. I haven't been caught walking in such a lightning-laden thunderstorm since the storm I experienced near the North Carolina border, and it refreshes my opinion that lightning is the most fearsome threat on the trail.

I hustle down a blue-blazed trail to Ore Hill Shelter, as happy as I have ever been to reach safety. Most of the group, who were just at the van enjoying a hot lunch, are now cowering from the elements.

From Glencliff, Arrow takes me to his parents' home for a shower and laundry. He returns me to the trailhead the next morning, and he will meet me again at the end of the day. All of the 9.5 miles I walk today will be spent going up and down one massive mountain, Mount Moosilauke. I am in the White Mountain National Forest.

At the foot of the mountain I see a porcupine. He is large with ungainly bristled armor, but he is agile enough to climb up a tree and cluck at me while I take his picture. The trail cuts through a dense forest of pines. Initially they are about twenty feet tall. As I go higher, they shrink down to perfect little three-foot-tall Christmas trees. Then they disappear altogether and the AT is above tree line for the first time. A naturalist is at the summit, speaking to a small group about the fragile nature of the alpine environment. Ken and Marcia are taking in the panorama. I say hello, but cannot linger in the cold breeze. I'm wearing shorts and a sleeveless shirt, which were barely warm enough at the foot of the mountain. At the peak it is at least ten degrees colder, and the unimpeded breeze makes it seem more so. Since Arrow is helping me to slack-pack today, I've left most of my gear, including my jacket, with him.

The descent on the north face of Moosilauke is the steepest I've experienced on the trail. The trail has no switchbacks, and most of the soil is washed away by erosion. Tree roots and bedrock lie exposed. The trail descends so sharply that I often turn to face the mountain and climb down backward so I can grab roots as handholds. A waterfall runs parallel to the path for much of the way, spraying mist onto the trail and making footing even more uncertain.

In some places, wooden steps are implanted into the bedrock. A notch is cut into the stone, and a railroad-tie-sized chunk of lumber is set into the notch, secured by spikes of rebar. These improvised steps are not uniformly spaced, being separated by a distance equivalent to two or three steps that would be placed in a building's stairwell. To get a feel for the difficulty, try taking stairwell steps two or three at a time without using the handrail. Spread some rocks and twigs on them, and then spray them down with water. If you still haven't been kicked out of the building, try it carrying a pack. On Moosilauke, a misstep would send me tumbling into a waterfall. Some of the timbers are loose and wobble when I land. Some are missing, giving me the unnerving visualization of one popping loose underfoot.

The descent ends at Kinsman Notch, where there is a road crossing and a parking area. Arrow is here, grilling more hamburgers and hotdogs. Hikers Duff, Ken, and Marcia stop to chat and eat. Arrow drives me to North Woodstock, which is situated at the intersection of two roads, the road that we are on and another road that crosses the trail sixteen miles north of here. Tomorrow I will slack-pack those sixteen miles and hitch a ride back into North Woodstock. I will repeat this slack-packing technique in the similarly situated towns of Gorham, Andover, and Rangeley.

I stay at the Cascade Lodge in North Woodstock. There are only a handful of rooms, and they ae ull upstairs and in desperate need of repairs. Downstairs is cluttered and yellowed by smoke. There is old furniture, tables mounded with papers, and overflowing hiker boxes. A computer is tucked into the disarray at the rear of the room, and the owner's teenage grandson is affixed to the screen, so immobile that I nearly overlook him. A hiker can feel at home here, and it is by far the cheapest lodging in town.