B0041VYHGW EBOK (156 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

After the climactic series of disaster shots, the tone shifts one more time. A relatively lengthy series of underwater shots follows a scuba diver. He explores a sunken wreck encrusted with barnacles

(

10.89

).

It recalls the disasters just witnessed, especially the sinking ship (

10.88

). The music builds to a triumphant climax as the diver swims into the ship’s interior. The film ends on a long-held musical chord over more black leader and a final shot looking up toward the surface of the sea. Ironically, there is no “The End” title at this point.

10.89 A

Movie:

the diver in the final scene.

A Movie

has taken us through its disparate footage almost entirely by means of association. There is no argument about why we should find these images disturbing or why we should link volcanoes and earthquakes to sexual or military aggression. There are no categorical similarities between many of the things juxtaposed and no story told about them. Occasionally, Conner does use abstract qualities to compare objects, but this is only a small-scale strategy, not one that organizes the whole film.

In building its associations,

A Movie

uses the familiar formal principles of repetition and variation. Even though the images come from different films, certain elements are repeated, as with the series of horse shots in

segment 1

or the different airplanes. These repetitions form motifs that help unify the whole film.

Moreover, these motifs return in a distinct pattern. We have seen how the titles and leader of the opening come back in some way in all the segments and how the “nudie” shot of

segment 1

is similar to the one used with the submarine footage in

segment 3

. Interestingly, not a single motif that appears in

segment 2

returns in

segment 3

, creating a strong contrast between the two. But then

segment 4

picks up and varies many of the motifs of both 2 and 3. As in so many films, the ending thus seems to develop and return to earlier portions. The dead elephant, the tanks, and the race cars all hark back to the frantic race of

segment 2

, while the tribal people, the

Hindenburg

disaster, the planes, the ships, and the bridge collapse all continue motifs begun in 3. The juxtapositions that have obvious links play on repetition, while startling and obscure ones create contrast. Thus Conner has created a unified work from what would seem to be a disunified mass of footage.

The pattern of development is also strikingly unified.

Segment 1

is primarily amusing, and a sense of hurtling exhilaration also carries through most of

segment 2

, up to the car crashes. But we have seen that the subjects of all the shots in

segment 2

could also suggest aggression and violence, and they all relate in some way to the disasters to come.

Segment 3

makes this more explicit but uses some humor and playfulness as well. By

segment 4

, the mixture of tones has largely disappeared, and an intensifying sense of doom replaces it. Now even odd or neutral events seem ominous.

Unlike the more clear-cut

Koyaanisqatsi, A Movie

withholds explicit meanings. Still,

A Movie

’s constantly shifting associations invite us to reflect on a range of implicit meanings. From one standpoint, the film can be interpreted as presenting the devastating consequences of unbridled aggressive energy. The horrors of the modern world—warfare and the hydrogen bomb—are linked with more trivial pastimes, such as sports and risky stunts. We are asked to reflect on whether both may spring from the same impulse, perhaps a kind of death wish. This impulse may, in turn, be tied to sexual drives (the pornographic motif) and political repression (the recurring images of people in developing countries).

Another interpretation might see the film as commenting on how cinema itself stirs our emotions through sex, violence, and exotic spectacle. In this sense,

A Movie

is “a movie” like any other, with the important difference that its thrills and disasters are actual parts of our world.

What of the ending? The scuba diver epilogue also offers a wide range of implicit meanings. It returns to the beginning in a formal sense: along with the Hopalong Cassidy segment, it is the longest continuous action we get. It might offer a kind of hope, perhaps an escape from the world’s horrors. Or the images may suggest humankind’s final death. After despoiling the planet, the human can only return to the primeval sea.

Like much of

A Movie,

the ending is ambiguous, saying little but suggesting much. Certainly, we can say that it serves to relax the tension aroused by the mounting disasters. In this respect, it demonstrates the power of an associational formal system: its ability to guide our emotions and to arouse our thinking simply by juxtaposing different images and sounds.

Most fiction and documentary films photograph people and objects in full-sized, three-dimensional spaces. As we have seen, the standard shooting speed for such

live-action

filmmaking is typically 24 frames per second.

“Animation is not a genre, it’s a medium. And it can express any genre. I think people often sell it short. But ‘because it’s animated, it must be for kids.’ You can’t name another medium where people do.”

— Brad Bird, director,

The Incredibles

Animated

films are distinguished from live-action ones by the unusual kinds of work done at the production stage. Instead of continuously filming an ongoing action in real time, animators create a series of images by shooting one frame at a time. Between the exposure of each frame, the animator changes the subject being photographed. Daffy Duck does not exist to be filmed, but a carefully planned and executed series of slightly different drawings of Daffy can be filmed as single frames. When projected, the images create illusory motion comparable to that of live-action filmmaking. Anything in the world—or indeed the universe—that the filmmaker can manipulate can be animated by means of two-dimensional drawings, three-dimensional objects, or digital information stored in a computer.

Because animation is the counterpart to live action, any sort of film that can be filmed live can be made using animation. There are animated fiction films, both short and feature-length. There can also be animated documentaries, usually instructional ones. Animation provides a convenient way of showing things that are normally not visible, such as the internal workings of machines or the extremely slow changes of geological formations. Ari Folman took this idea further in his documentary

Waltz with Bashir.

After interviewing Israeli army veterans, he sought to represent their dreams and recollections in hallucinatory animated imagery

(

10.90

).

10.90 A recurring memory image in

Waltz with Bashir

shows soldiers wading toward an eerily beautiful bombardment.

With its potential for distortion and pure design, animation lends itself readily to experimental filmmaking as well. Many classic experimental animated films employ either abstract or associational form. For example, both Oskar Fischinger and Norman McLaren made films by choosing a piece of music and arranging abstract shapes to move in rhythm to the sound track. Later in this chapter, we’ll examine an example of abstract animation in Robert Breer’s

Fuji.

There are several distinct types of animation. The most familiar is

drawn

animation. From almost the start of cinema, animators drew and photographed long series of cartoon images. At first, they drew on paper, but copying the entire image, including the setting, over and over proved too time-consuming. During the 1910s, studio animators introduced clear rectangular sheets of celluloid, nicknamed

cels.

Characters and objects could be drawn on different cels, and these could then be layered like a sandwich on top of an opaque painted setting. The whole stack of cels would then be photographed. New cels showing the characters and objects in slightly different positions could then be placed over the same background, creating the illusion of movement

(

10.91

).

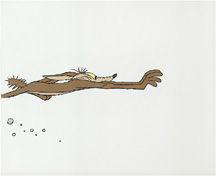

10.91 Two layered cels from a Road Runner cartoon, with Wile E. Coyote on one cel and the patches of flying dust on another.

The cel process allowed animators to save time and to split up the labor among assembly lines of people doing drawing, coloring, photography, and other jobs. The most famous cartoon shorts made during the 1930s to the 1950s were made with cels. Warner Bros. created characters such as Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, and Tweety Bird; Paramount had Betty Boop and Popeye; Disney made both shorts (Mickey Mouse, Pluto, Goofy) and, beginning with

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs

in 1937, feature-length cartoons.

Cel animation continued well into the 1990s, with big-budget studio cartoons employing

full

animation. This approach renders figures in fine detail and supplies them with tiny, nonrepetitive movements. (See

4.133

, as well as

5.137

–5.139.) Cheaper productions use

limited

animation, with only small sections of the image moving from frame to frame. Limited animation is mainly used on television, although Japanese theatrical features

(

10.92

)

exploited it to create flat, posterlike images.

10.92 Limited animation in

Silent Möbius.

Some independent animators have continued to draw on paper. Robert Breer, for example, uses ordinary white index cards for his witty, quasi-abstract animated films. We will examine his

Fuji

shortly.