B0041VYHGW EBOK (166 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

As the setting and the use of the neighborhood radio station suggest,

Do The Right Thing

centers more on the community as a whole than on a few central characters. On the one hand, there are older traditions that are worth preserving, represented by the elderly characters: the moral strength of the matriarch Mother Sister, the decency and courage of Da Mayor, the wit and common sense of the three chatting men—ML, Sweet Dick Willie, and Coconut Sid. On the other hand, the younger people need to create a new community spirit by overcoming sexual and racial conflict. The women are portrayed as trying to make the angry young African-American men more responsible. Tina pressures Mookie to pay more attention to her and to their son; Jade lectures both her brother Mookie and the excitable Buggin’ Out, telling the latter he should direct his energies toward doing “something positive in the community.” The emphasis on community is underscored by the fact that most of the characters address one another by their nicknames.

One of the main conflicts in the film arises when Sal refuses to add some pictures of African-American heroes to his “Hall of Fame” photo gallery of Italian Americans. Sal might have become a sort of elder statesman in the community, where he has run his pizzeria for 25 years. He seems to like the kids who eat his pizza, but he also views the restaurant as entirely his domain, emphatically declaring that he’s the boss. Thus he reveals his lack of real integration into the community and ends by goading the more hot-headed elements into attacking him.

In creating its community,

Do The Right Thing

includes an unusually large number of characters for a classical film. Again, however, a closer examination shows that only eight of them provide the main causal action: Mookie, Tina, Sal, Sal’s son Pino, Mother Sister, Da Mayor, Buggin’ Out, and Radio Raheem. The others, intriguing or amusing as they may be, are more peripheral, mainly reacting to the action set in motion by these characters’ conflicts and goals. (Some modern American screenwriting manuals recommend seven to eight important characters as the maximum for a clearly comprehensible film, so Lee is not departing from tradition as much as it might seem.) Moreover, the main causal action falls into two related lines, as in traditional Hollywood films: one involves the community’s relations to Sal and his sons; the other deals with Mookie’s personal life. Mookie becomes the pivotal figure, linking the two lines of action.

Do The Right Thing

also departs from classical narrative conventions in some ways. Consider the characters’ goals. Usually, the main characters of a film formulate clear-cut, long-range goals that bring them into conflict with one another. In

Do The Right Thing,

most of the eight main characters create goals only sporadically; the goals are sometimes introduced fairly late in the film, and some are vague.

Buggin’ Out, for example, demands that Sal put up pictures of some black heroes on the pizzeria wall. When Sal refuses and throws him out, Buggin’ Out shouts to the customers to boycott Sal’s. Yet a little while later, when he tries to persuade his neighbors to participate in the boycott, they all refuse, and his project seems to sputter out. Then, later in the film, Radio Raheem and the mentally retarded Smiley agree to join him. Their visit to the pizzeria to threaten Sal then precipitates the climactic action. Ironically, Buggin’ Out’s goal is briefly achieved when Smiley puts a photograph of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. on the wall of the burning pizzeria—but by that point, Buggin’ Out is on his way to jail.

Mookie’s goal is hinted at when we first see him. He is counting money, and he constantly emphasizes that he just wants to work and get paid. His repeated reference to the fact that he is due to be paid in the evening creates the film’s only appointment, helping to emphasize the compressed time scheme. Yet his purpose remains unclear. Does he simply want the money so that he can move out of his sister’s apartment, as she demands? Or does he also plan to help Tina care for their son?

Sal’s goal is similarly vague—to keep operating his pizzeria in the face of rising tensions. Da Mayor articulates one of the few really clear-cut goals in the film when he tells Mother Sister that someday she will be nice to him. After he persistently acts courteously and bravely, she does in fact relent and become his friend. Sal’s virulently racist son Pino has a goal—trying to convince his father that they should sell the pizzeria and get out of the black neighborhood. Perhaps he will get his desire at the end, although the narrative leaves open the question of whether Sal will rebuild.

In traditional classical films, clear-cut goals generate conflict, since the characters’ desires often clash. Lee neatly reverses this pattern by playing down goals but creating a community that is full of conflict from the very beginning of the film. Racial and sexual arguments break out frequently, and insults fly. Such conflict is tied to the fact that

Do The Right Thing

is a social-problem film. Its didactic message gives it much of its overall unity. Everything that happens relates to a central question: With the community riven with such tensions, what can be done to heal it?

The characters’ goals and actions suggest some of the possible ways of reacting to the situation. Some of the characters desire simply to avoid or escape this tense atmosphere—Pino by leaving the neighborhood, Da Mayor by overcoming Mother Sister’s animosity. Mookie attempts to stay out of trouble by not siding with either Sal or his black friends in their escalating quarrel; only the death of Radio Raheem drives him to join in, and indeed initiate, the attack on Sal’s pizzeria.

“It’s funny how the script is evolving into a film about race relations. This is America’s biggest problem, always has been (since we got off the boat), always will be. I’ve touched upon it in my earlier works, but I haven’t yet dealt with it head on as a primary subject.”

— Spike Lee, from the production journal of

Do The Right Thing

Other characters attempt to solve their problems. One central goal is Tina’s desire to get Mookie to behave more responsibly and spend time with her and with their child. There is a suggestion at the end that she may be succeeding to some extent. Mookie gets his pay from Sal and says that he will get another job and that he’s going to see his son. The last shot shows him walking down the now-quiet street, hinting that he may really visit his son more regularly in the future.

The central question in the film, however, is not whether any one character will achieve his or her goals. It is whether the pervasive conflicts can be resolved peacefully or violently. As the DJ says on the morning after the riot, “Are we gonna live together—together are we gonna live?”

Do The Right Thing

leaves unanswered questions at the end. Will Sal rebuild? Is Mookie really going back to see his son? Most important, though the conflict that flared up has died down, the tension is still present in the community, waiting to resurface. The old problem of how to tame it remains, and so the film does not achieve complete closure. Indeed, such an ending is typical of the social-problem genre. While the immediate conflict may be resolved, the underlying dilemma that caused it remains.

That is also why there is a deliberate ambiguity at the end. Just as we are left at the end of

Citizen Kane

to wonder whether the revelation of the meaning of “Rosebud” explains Kane’s character, in

Do The Right Thing

we are left to ponder what “the right thing” is. The film continues after the final story action, with two nondiegetic quotations from Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. The King passage advocates a nonviolent approach to the struggle for civil rights, while Malcolm X condones violence in self-defense.

Do The Right Thing

refuses to suggest which leader is right—although the narrative action and use of the phrase “by any means necessary” at the end of the credits seem to weight the film’s position in favor of Malcolm X. Still, the juxtaposition of the two quotations, in combination with the open-ended narrative, also seems calculated to spur debate. Perhaps the implication is that each position is viable under certain circumstances. The line of action involving Sal’s pizzeria ends in violence; yet at the same time, Da Mayor is able to win Mother Sister’s friendship gently.

As in its narrative structure, the style of

Do The Right Thing

stretches the traditional techniques of classical filmmaking. It begins with a credits sequence during which Rosie Perez performs a vigorous and aggressive dance to the rap song “Fight the Power.” The editing here is strongly discontinuous, as she wears sometimes a red dress, sometimes a boxer’s outfit, and sometimes a jacket and pants. One moment she is on the street; then she suddenly appears in an alley. This brief sequence, which is not part of the narrative, employs the flashy style made familiar by MTV and by television commercials. Lee himself has made both music videos and commercials.

Nothing in the rest of

Do The Right Thing

is quite as discontinuous or extreme as the credits sequence, but Lee uses a loose version of the traditional continuity system. He draws on a broad range of techniques, handling some scenes in virtuosic long takes, others with shot/reverse shot, and still others with extensive camera movements. In two cases, he even cuts together two takes of the same action, so that the plot presents a single important story event twice: when Mookie first kisses Tina and when the garbage can hits Sal’s window. One result of this varied style is a suggestion of the vigor and variety of the community itself.

Despite the many quick changes of locale, Lee uses continuity devices to establish space clearly. As we saw in

Chapter 6

, he is adept at using shot/reverse shot without breaking the axis of action (

6.79

–

6.84

, from

She’s Gotta Have It,

pp. 243

–244).

Do The Right Thing

similarly contains many shot/reverse-shot conversations where the eyelines are consistent

(

11.19

,

11.20

).

Yet Lee opts to handle other conversations without any editing. The lengthy conversation in which Pino asks Sal to sell the pizzeria is handled in one long take

(

11.21

–

11.23

).

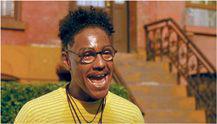

11.19 In

Do The Right Thing,

this shot/reverse-shot conversation between Jade and …

11.20 … Buggin’ Out uses correct eyeline directions.

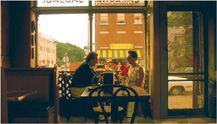

11.21 This long take in

Do The Right Thing

begins with a track-in …

11.22 … toward Sal and Pino and lasts until Smiley appears outside …