B0041VYHGW EBOK (164 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

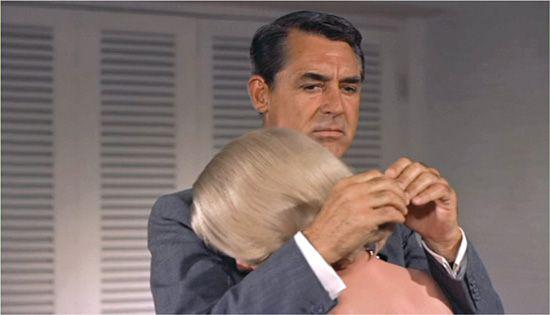

11.7 … later in her hotel room, when she tries to embrace him after his narrow escape from death, his hands freeze in place, as if he fears touching her.

Still, narrative unity alone cannot explain the film’s strong emotional appeal. In

Chapter 3

’s discussion of narration, we used

North by Northwest

as an example of a hierarchy of knowledge (

p. 95

). We suggested that as the film progresses, sometimes we are restricted to what Roger knows, but at other times, we know significantly more than he does. At still other moments, our range of knowledge, while greater than Roger’s, is not as great as that of other characters. Now we are in a position to see how this constantly changing process helps create suspense and surprise across the whole film.

The most straightforward way in which the film’s narration controls our knowledge is through the numerous optical point-of-view (POV) shots Hitchcock employs. This device yields a degree of subjective depth: we see what a character sees more or less as she or he sees it. More important here, the optical POV shot restricts us only to what that character learns at that moment. Hitchcock gives almost every major character a shot of this sort. The very first optical POV we see in the film is taken from the position of the two spies who are watching Roger apparently respond to the paging of George Kaplan

(

11.8

,

11.9

).

Later, we view events through the eyes of Eve, of Van Damm, of his henchman Leonard, and even of a clerk at a ticket counter.

11.8 Early in

North by Northwest,

a shot of two spies looking off left is followed by …

11.9 … a shot of Thornhill from their POV.

Nevertheless, by far the greatest number of POV shots are attached to Thornhill. Through his eyes, we see his approach to the Townsend mansion, the mail he finds in the library, his drunken drive along the cliff, and the airplane that is “crop dusting where there ain’t no crops.” Some of the most extreme uses of optical POV give us Roger’s experience directly

(

11.10

,

11.11

).

11.10 An advancing truck as seen by Thornhill.

11.11 A trooper’s fist coming toward the camera, again from Thornhill’s POV.

Thornhill’s optical POV shots function within a narration that is often restricted not only to what he

sees

but also to what he

knows.

The plane attack at Prairie Stop, for example, is confined wholly to Roger’s range of knowledge. Hitchcock could have cut away from Roger waiting by the road in order to show us the villains plotting in their plane, but he does not. Similarly, when Roger is searching for George Kaplan’s room and gets a phone call from the two henchmen, Hitchcock could have used crosscutting to show the villains phoning from the lobby. Instead, we learn that they are in the hotel no sooner than Roger does. And when Thornhill and his mother hurry out of the room, Hitchcock does not use crosscutting to show the villains in pursuit. This makes it more startling when Roger and his mother get on the elevator and discover the two men there already. In scenes like these, confining us to Thornhill’s range of knowledge sharpens the effect of surprise.

Sometimes the same effect comes from the film’s restricting us to Roger’s range of knowledge and then giving us information that he does not at the moment have. On

p. 89

, we suggested that this sort of surprise occurs when the plot shifts us from Roger’s escape from the United Nations murder to the scene at the USIA office, where the staff discuss the case. At this point, we learn that there is no George Kaplan—something that Roger does not discover for many more scenes to come.

The abrupt shifts from Roger’s range of knowledge yield a similar effect during the train trip from New York to Chicago. During several scenes, Eve Kendall helps Thornhill evade the police. Finally, they are alone and relatively safe in her compartment. At this point, the narration shifts the range of knowledge. A message is delivered to another compartment. Hands unfold a note: “What do I do with him in the morning?” The camera then moves back to show us Leonard and Van Damm reading the message. Now we know that Eve is not merely a sympathetic stranger but someone working for the spy ring. Again, Roger will learn this much later. In such cases, the move to a less restricted range of information lets the narration put us a notch higher than Thornhill in the hierarchy of knowledge.

Such moments evoke surprise, but we have already noted that Hitchcock claimed in general to prefer to generate suspense (

p. 90

). Suspense is created by giving the spectator more information than the character has. In the scenes we have just mentioned, once the effect of surprise has been achieved, the narration can use our superior knowledge to build suspense across several sequences. After the audience learns that there is no George Kaplan, every attempt by Thornhill to find him builds up suspense about whether he will discover the truth. Once we learn that Eve is working for Van Damm, her message to Roger on behalf of Kaplan will make us uncertain as to whether Roger will fall into the trap.

In these examples, suspense arises across a series of scenes. Hitchcock also uses unrestricted narration to build up suspense within a single scene. His handling of the UN murder differs markedly from his treatment of the scene showing Roger and his mother in Kaplan’s hotel room. In the hotel scene, Hitchcock refused to employ crosscutting to show the spies’ pursuit. At the United Nations, however, he crosscuts between Roger, who is searching for Townsend, and Valerian, one of the thugs following him. Just before the murder, a rightward tracking shot establishes Valerian’s position in the doorway (something of which Roger is wholly unaware). Here crosscutting and camera movement widen our frame of knowledge and create suspense as to the scene’s outcome.

The sequence in Chicago’s Union Station is handled similarly. Here crosscutting moves us from Roger shaving in the men’s room to Eve talking on the phone. Then another lateral tracking shot reveals that she is talking to Leonard, who is giving her orders from another phone booth. We now are certain that the message she will give Roger will endanger him, and the suspense is increased accordingly. (Note, however, that the narration does not reveal the conversation itself. As often happens, Hitchcock conceals certain information for the sake of further surprises.)

Thornhill’s knowledge expands as the lines of action develop. On the third day, he discovers that Eve is Van Damm’s mistress, that she is a double agent, and that Kaplan doesn’t exist. He agrees to help the Professor in a scheme to clear Eve of any suspicion in Van Damm’s eyes. When the scheme (a faked shooting in the Mount Rushmore restaurant) succeeds, Roger believes that Eve will leave Van Damm. Once more, however, he has been duped (as we have). The Professor insists that she must go off to Europe that night on Van Damm’s private flight. Roger resists, but he is knocked out and held captive in a hospital. His escape leads to the final major sequence of the film.

Here the plot resolves all its lines of action, and the narration continues to expand and contract our knowledge for the sake of suspense and surprise. This climactic sequence comprises almost 300 shots and runs for several minutes, but we can conveniently divide the sequence into three sections.

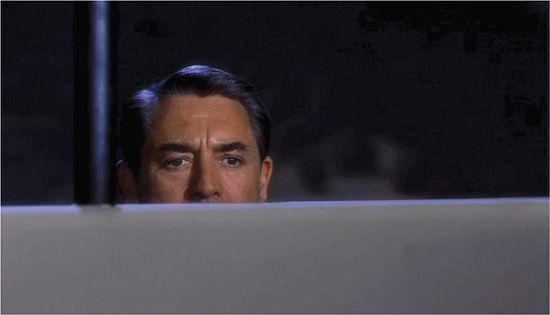

In the first section, Roger arrives at Van Damm’s house and reconnoiters. He clambers up to the window and learns from a conversation between Leonard and Van Damm that the piece of sculpture they bought at the auction contains microfilm. More important, he watches Leonard inform Van Damm that Eve is an American agent. This action is conveyed largely through optical POV (

11.12

,

11.13

; also

3.15

–

3.17

). At two moments, as Leonard and Van Damm face each other, the narration gives us optical POV shots from each man’s standpoint

(

11.14

,

11.15

),

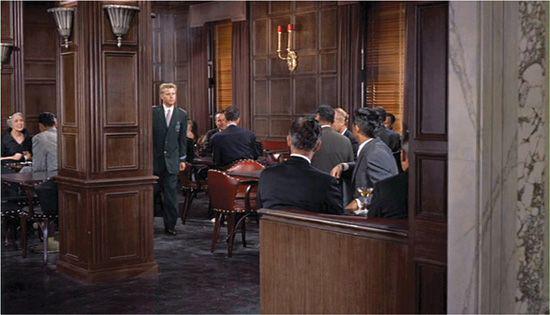

but these are enclosed, so to speak, within Roger’s ongoing witnessing of the situation. For the first time in the film, Roger has more knowledge of the situation than any other character. He knows how the smuggling has been done, and he discovers that the villains intend to murder Eve.

11.12 In

North by Northwest,

Thornhill watches in dismay …