B0041VYHGW EBOK (173 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

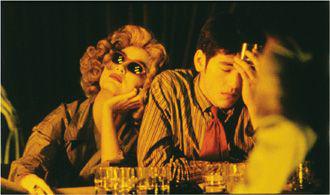

11.63 Officer 1 at home, disconsolate.

11.64 Officer 2 broods about his lost love.

They need a change—or, according to the film’s most pervasive motif, a change of menu. Food is central to both stories, announced at the start in the headlong tracking shots through Chungking Mansions, the cafés filled with eaters. Officer 1 measures the time he waits for May (who loved pineapple) in pineapple cans, each day buying one with a May 1 expiration date. On the last day, he gorges himself, emptying the 30 cans he has saved. When he meets the blonde, he asks if she likes pineapple. Similarly, Officer 2 always orders chef’s salads at the Midnight Express. In contrast, women are presented as craving varied menus. As the blonde studies Officer 1 in the bar, her voice-over commentary remarks, “Knowing someone doesn’t mean keeping them. People change. A person may like pineapple today and something else tomorrow.” When Officer 2 brings home pizza and fish and chips, his girlfriend leaves him. He muses that she realized that she had a choice of lovers as well as dinners.

The food motif goes on to define the men’s attitudes toward change. While the blonde sleeps in a Chungking Mansions hotel room, Officer 1 stuffs himself with hamburgers, salads, and fries. Once outside, he thinks that she has forgotten him, but her pager message (“Happy birthday”) leads him to wish that the expiration date on his memory of her will last forever. No longer treating a girlfriend as a fastfood snack, Officer 1’s sense of time has expanded; instead of seeking a new future, he treasures a moment in the past

(

11.65

).

11.65 After his morning run, Officer 1 gets the pager message wishing him a happy birthday.

As the countergirl Faye invades Officer 2’s life, she replaces his cheap tinned fish with another brand, spikes his water jug to help him sleep, and pushes him out of his self-pity (in which he imagines his towel crying and his soap wasting away). When she skips their date, she leaves him a fake boarding pass she inks onto a napkin; at first he discards it, but then, in a composition paralleling that of Officer 1’s meditation on his pager message, he dries it in a snack-shop rotisserie

(

11.66

).

A year later, Officer 2 has embraced a varied menu. He has bought the Midnight Express, and when Faye returns, he persuades her to write him a new pass. Before he had been reluctant to travel with her, but now, when she asks where he wants to fly, he replies, “Wherever you want to take me.” He has broken out of routine and is willing to accept change.

11.66 Officer 2 had discarded the mock boarding pass Faye left him; now he waits for it to dry so he can read it.

This last scene sums up another motif, airplane flight, that runs through both parts and marks parallels. Both are associated with women’s desire for change. In the first part, the blonde prepares her drug mules for a flight, and she flees her crime by taking an early plane out. In the second part, Officer 2’s air hostess is replaced by Faye, who, when she first meets her rival, measures herself against her

(

11.67

).

Musical motifs also signal the importance of change. The repeated reggae song in the first part states, “It’s not every day that’s gonna be the same way, there must be a change somehow.” The second part highlights the song “What a Difference a Day Makes” and repeats the Mamas and Papas’ “California Dreamin’,” which expresses a wish to leave for sunnier surroundings. Several pictorial motifs link the two main women, including their shoes, their dark glasses, and their habit of slipping into reverie

(

11.68

,

11.69

).

11.67 Faye, who will become a flight attendant, measures herself against the woman who dumped Officer 2.

If the film’s primary theme is indeed the acceptance of change as part of love, then the two parts are cunningly designed to lead the audience toward it indirectly. The first part begins with the blonde hurrying through Chungking Mansions, then shows Officer 1 racing after a criminal and colliding with her before moving on. Her femme fatale disguise and the drug deal suggest that this is the start of a crime thriller (see

pp. 322

–324). But soon the smuggling situation is overwhelmed by Officer 1’s romantic yearnings, and the blonde woman’s abrupt shooting of her boss ends the crime line of action. The second tale begins, and Officer 2’s placid routine and personal problems take over. The thriller elements have served largely as bait, luring us to study the characters before the plot switches genres and becomes an open-ended romantic comedy.

Wong signals the genre shift through a stylistic parallel. As Officer 1 collides with the blonde, the frame freezes, and in voice-over he says, “Fifty-seven hours later I fell in love with this woman.” When at the end of the first part Officer 1 revisits the Midnight Express, he bumps into Faye

(

11.70

).

His commentary remarks, “Six hours later …” The image fades out and fades in on Officer 2 approaching the snack bar

(

11.71

),

and we hear Officer 1 continue, “… She fell in love with another man.” We will never see Officer 1 again. These voice-over remarks (highly implausible on grounds of realism—how could Officer 1 know that Faye falls in love with Officer 2?) mark the film’s romantic parallels explicitly.

11.71

Part two

begins with Officer 2 approaching the Midnight Express; he will replace Officer 1 as the film’s male protagonist.