B0041VYHGW EBOK (38 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

The narrator may be a

character

in the story. We are familiar with this convention from literature, as when Huck Finn or Jane Eyre recounts a novel’s action. In Edward Dmytryk’s film

Murder, My Sweet,

the detective tells his story in flashbacks, addressing the information to inquiring policemen. In the documentary

Roger and Me,

Michael Moore frankly acknowledges his role as a character narrator. He starts the film with his reminiscences of growing up in Flint, Michigan, and he appears on camera in interviews with workers and in confrontations with General Motors security staff.

A film can also use a

noncharacter narrator.

Noncharacter narrators are common in documentaries. We never learn who belongs to the anonymous “voice of God” we hear in

The River, Primary,

or

Hoop Dreams.

A fictional film may employ this device as well.

Jules and Jim

uses a dry, matter-of-fact commentator to lend a flavor of objectivity, while other films might call on this device to lend a sense of realism, as in the urgent voice-over we hear during

The Naked City.

A film may play on the character/noncharacter distinction by making the source of a narrating voice uncertain. In

Film About a Woman Who …,

we might assume that a character is the narrator, but we cannot be sure because we cannot tell which character the voice belongs to. In fact, it may be coming from an external commentator.

Note that either sort of narrator may present various sorts of narration. A character narrator is not necessarily restricted and may tell of events that she or he did not witness, as the relatively minor figure of the village priest does in John Ford’s

The Quiet Man.

A noncharacter narrator need not be omniscient and could confine the commentary to what a single character knows. A character narrator might be highly subjective, telling us details of his or her inner life, or might be objective, confining his or her recounting strictly to externals. A noncharacter narrator might give us access to subjective depths, as in

Jules and Jim,

or might stick simply to surface events, as does the impersonal voice-over commentator in

The Killing.

In any case, the viewer’s process of picking up cues, developing expectations, and constructing an ongoing story out of the plot will be partially shaped by what the narrator tells or doesn’t tell.

We can summarize the shaping power of narration by considering George Miller’s

The Road Warrior

(also known as

Mad Max II

). The film’s plot opens with a voiceover commentary by an elderly male narrator who recalls “the warrior Max.” After presenting exposition that tells of the worldwide wars that led society to degenerate into gangs of scavengers, the narrator falls silent. The question of his identity is left unanswered.

The rest of the plot is organized around Max’s encounter with a group of peaceful desert people. They want to flee to the coast with the gasoline they have refined, but they’re under siege by a gang of vicious marauders. The plot action involves Max’s agreement to work for the settlers in exchange for gasoline. Later, after a brush with the gang leaves him wounded, his dog dead, and his car demolished, Max commits himself to helping the people escape their compound. The struggle against the encircling gang comes to its climax in an attempt to escape with a tanker truck, with Max at the wheel.

Max is at the center of the plot’s causal chain; his goals and conflicts propel the developing action. Moreover, after the anonymous narrator’s prologue, most of the film is restricted to Max’s range of knowledge. Like Philip Marlowe in

The Big Sleep,

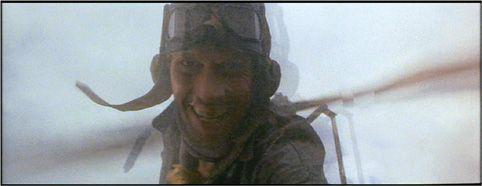

Max is present in every scene, and almost everything we learn gets funneled through him. The depth of story information is also consistent. The narration provides optical point-of-view shots as Max drives his car

(

3.36

)

or watches a skirmish through a telescope. When he is rescued after his car crash, his delirium is rendered as perceptual subjectivity, using the conventional cues of slow motion, superimposed imagery, and slowed-down sound

(

3.37

).

All of these narrational devices encourage us to sympathize with Max.

3.36 A point-of-view shot as Max drives up to an apparently abandoned gyro in

The Road Warrior.

3.37 The injured Max’s dizzy view of his rescuer uses double exposure.

At certain points, however, the narration becomes more unrestricted. This occurs principally during chases and battle scenes, when we witness events Max probably does not know about. In such scenes, unrestricted narration functions to build up suspense by showing both pursuers and pursued or different aspects of the battle. At the climax, Max’s truck successfully draws the gang away from the desert people, who escape to the south. But when his truck overturns, Max—and we—learn that the truck holds only sand. It has been a decoy. Thus our restriction to Max’s range of knowledge creates a surprise.

“Narrative tension is primarily about withholding information.”

— Ian McEwan, novelist

There is still more to learn, however. At the very end, the elderly narrator’s voice returns to tell us that he was the feral child whom Max had befriended. The desert people drive off, and Max is left alone in the middle of the highway. The film’s final image—a shot of the solitary Max receding into the distance as we pull back

(

3.38

)

—suggests both a perceptual subjectivity (the boy’s point of view as he rides away from Max) and a mental subjectivity (the memory of Max dimming for the narrator).

3.38 As the camera tracks away from Max, we hear the narrator’s voice: “And the Road Warrior? That was the last we ever saw of him. He lives now only in my memories.”

In

The Road Warrior,

then, the plot’s form is achieved not only by causality, time, and space but also by a coherent use of narration. The main portion of the film channels our expectations through an attachment to Max, alternating with more unrestricted portions. In turn, this section is framed by the mysterious narrator who puts all the events into the distant past. The narrator’s presence at the opening leads us to expect him to return at the end, perhaps explaining who he is. Thus both the cause–effect organization and the narrational patterning help the film give us a unified experience.

The number of possible narratives is unlimited. Historically, however, fictional filmmaking has tended to be dominated by a single tradition of narrative form. We’ll refer to this dominant mode as the “classical Hollywood cinema.” This mode is called “classical” because of its lengthy, stable, and influential history, and “Hollywood” because the mode assumed its most elaborate shape in American studio films. The same mode, however, governs many narrative films made in other countries. For example,

The Road Warrior,

though an Australian film, is constructed along classical Hollywood lines. And many documentaries, such as

Primary,

rely on conventions derived from Hollywood’s fictional narratives.

This conception of narrative depends on the assumption that the action will spring primarily from

individual characters as causal agents.

Natural causes (floods, earthquakes) or societal causes (institutions, wars, economic depressions) may affect the action, but the narrative centers on personal psychological causes: decisions, choices, and traits of character.

Typically what gets this sort of narragive going is someone’s

desire.

A character wants something. The desire sets up a

goal,

and the course of the narrative’s development will most likely involve the process of achieving that goal. In

The Wizard of Oz,

Dorothy has a series of goals, as we’ve seen: from saving Toto from Miss Gulch to getting home from Oz. The latter goal creates short-term goals along the way: getting to the Emerald City and then killing the Witch.

If this desire to reach a goal were the only element present, there would be nothing to stop the character from moving quickly to achieve it. But there is a counterforce in the classical narrative: an opposition that creates conflict. The protagonist comes up against a character with opposing traits and goals. As a result, the protagonist must seek to change the situation so that he or she can achieve the goal. Dorothy’s desire to return to Kansas is opposed by the Wicked Witch, whose goal is to obtain the Ruby Slippers. Dorothy must eventually eliminate the Witch before she is able to use the slippers to go home. We shall see in

His Girl Friday

how the two main characters’ goals conflict until the final resolution (

pp. 444

–445).

“Movies to me are about wanting something, a character wanting something that you as the audience desperately want him to have. You, the writer, keep him from getting it for as long as possible, and then, through whatever effort he makes, he gets it.”

— Bruce Joel Rubin, screenwriter,

Ghost

Cause and effect imply

change.

If the characters didn’t desire something to be different from the way it is at the beginning of the narrative, change wouldn’t occur. Therefore characters’ traits and wants are a strong source of causes and effects.

But don’t all narratives have protagonists of this sort? Actually, no. In 1920s Soviet films, such as Sergei Eisenstein’s

Potemkin, October,

and

Strike,

no

individual

serves as protagonist. In films by Eisenstein and Yasujiro Ozu, many events are seen as caused not by characters but by larger forces (social dynamics in the former, an overarching nature in the latter). In narrative films such as Michelangelo Antonioni’s

L’Avventura,

the protagonist is not active but passive. So the striving, goal-oriented protagonist, though common, doesn’t appear in every narrative film.

In the classical Hollywood narrative, psychological causes tend to motivate most other narrative events. Time is subordinated to the cause–effect chain. The plot will omit significant durations in order to show only events of causal importance. (The hours Dorothy and her entourage spend walking on the Yellow Brick Road are omitted, but the plot dwells on the moments during which she meets a new character.) The plot will arrange story chronology so as to present the cause–effect chain most strikingly. For instance, in one scene of

Hannah and Her Sisters,

Mickey (played by Woody Allen) is in a suicidal depression. When we next see him several scenes later, he is bubbly and cheerful. Our curiosity about this abrupt change enhances his comic explanation to a friend, via a flashback, that he achieved a serene attitude toward life while watching a Marx Brothers film.