B0041VYHGW EBOK (39 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

CONNECT TO THE BLOG

For a discussion of how characters’ goals can be crucial to major transitions in the plot, see “Time goes by turns,” at

www.davidbordwell.net/blog/?p=2448

.

Specific devices make plot time depend on the story’s cause–effect chain. The

appointment

motivates characters’ encountering each other at a specific moment. The

deadline

makes plot duration dependent on the cause–effect chain. Throughout, motivation in the classical narrative film strives to be as clear and complete as possible—even in the fanciful genre of the musical, in which song-and-dance numbers become motivated as either expressions of the characters’ emotions or stage shows mounted by the characters.

Narration in the classical Hollywood cinema exploits a variety of options, but there’s a strong tendency for it to be objective in the way discussed on

pages 95

–97. It presents a basically objective story reality, against which various degrees of perceptual or mental subjectivity can be measured. Classical cinema also tends toward fairly unrestricted narration. Even if we follow a single character, there are portions of the film giving us access to things the character does not see, hear, or know.

North by Northwest

and

The Road Warrior

remain good examples of this tendency. This weighting is overridden only in genres that depend heavily on mystery, such as the detective film, with its reliance on the sort of restrictiveness we saw at work in

The Big Sleep.

Finally, most classical narrative films display a strong degree of

closure

at the end. Leaving few loose ends unresolved, these films seek to complete their causal chains with a final effect. We usually learn the fate of each character, the answer to each mystery, and the outcome of each conflict.

Again, none of these features is necessary to narrative form in general. There is nothing to prevent a filmmaker from presenting the dead time, or narratively unmotivated intervals between more significant events. (Jean-Luc Godard, Carl Dreyer, and Andy Warhol do this frequently, in different ways.) The filmmaker’s plot can also reorder story chronology to make the causal chain

more

perplexing. For example, Jean-Marie Straub and Daniéle Huillet’s

Not Reconciled

moves back and forth among three widely different time periods without clearly signaling the shifts. Duˇsan Makavejev’s

Love Affair, or the Case of the Missing Switchboard Operator

uses flash-forwards interspersed with the main plot action; only gradually do we come to understand the causal relations of these flash-forwards to the present-time events. More recently, puzzle films (

pp. 88

–89) tease the audience to find clues to enigmatic narration or story events.

CONNECT TO THE BLOG

The classical approach to narrative is still very much alive, as we show in “Your trash, my treasure.”

The filmmaker can also include material that is unmotivated by narrative cause and effect, such as the chance meetings in Truffaut’s films, the political monologues and interviews in Godard’s films, the intellectual montage sequences in Eisenstein’s films, and the transitional shots in Ozu’s work. Narration may be completely subjective, as in

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari,

or it may hover ambiguously between objectivity and subjectivity, as in

Last Year at Marienbad.

Finally, the filmmaker need not resolve all of the action at the end; films made outside the classical tradition sometimes have quite open endings.

We’ll see in

Chapter 6

how the classical Hollywood mode also makes cinematic space serve causality through continuity editing. For now we can simply note that the classical mode tends to treat narrative elements and narrational processes in specific and distinctive ways. For all of its effectiveness, the classical Hollywood mode remains only one system among many that can be used for constructing narrative films.

Citizen Kane

With its unusual organizational style,

Citizen Kane

invites us to analyze how principles of narrative form operate across an entire film.

Kane

’s investigation plot carries us toward analyzing how causality and goal-oriented characters may operate in narratives. The film’s manipulations of our knowledge shed light on the story–plot distinction.

Kane

also shows how ambiguity may arise when certain elements aren’t clearly motivated. Furthermore, the comparison of

Kane

’s beginning with its ending indicates how a film may deviate from the patterns of classical Hollywood narrative construction. Finally,

Kane

clearly shows how our experience can be shaped by the way that narration governs the flow of story information.

Citizen Kane

We saw in

Chapter 2

that our experience of a film depends heavily on the expectations we bring to it and the extent to which the film confirms them. Before you saw

Citizen Kane,

you may have known only that it is regarded as a film classic. Such an evaluation would not give you a very specific set of expectations. A 1941 audience would have had a keener sense of anticipation. For one thing, the film was rumored to be a disguised version of the life of the newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst. Spectators would thus be looking for events and references keyed to Hearst’s life.

Several minutes into the film, the viewer can form more specific expectations about pertinent genre conventions. The early “News on the March” sequence suggests that this film may be a fictional biography, and this hint is confirmed once the reporter, Thompson, begins his inquiry into Kane’s life. The film does indeed follow the conventional outline of the fictional biography, which typically covers an individual’s whole life and dramatizes certain episodes in the period. Examples of this genre would be

Anthony Adverse

(1936) and

The Power and the Glory

(1933). (The latter film is often cited as an influence on

Citizen Kane

because of its complex use of flashbacks.)

The viewer can also quickly identify the film’s use of conventions of the newspaper reporter genre. Thompson’s colleagues resemble the wisecracking reporters in

Five Star Final

(1931),

Picture Snatcher

(1933), and

His Girl Friday

(1940). In this genre, the action usually depends on a reporter’s dogged pursuit of a story against great odds. We therefore expect not only Thompson’s investigation but also his triumphant discovery of the truth. In the scenes devoted to Susan, there are also some conventions typical of the musical film: frantic rehearsals, backstage preparations, and, most specifically, the montage of her opera career, which parodies the conventional montage of singing success in films like

Maytime

(1937). More broadly, the film evidently owes something to the detective genre, since Thompson is aiming to solve a mystery (Who or what is Rosebud?), and his interviews resemble those of a detective questioning suspects in search of clues.

Note, however, that

Kane

’s use of genre conventions is somewhat equivocal. Unlike many biographical films,

Kane

is more concerned with psychological states and relationships than with the hero’s public deeds or adventures. As a newspaper film,

Kane

is unusual in that the reporter fails to get his story. And

Kane

is not exactly a standard mystery, since it answers some questions but leaves others unanswered.

Citizen Kane

is a good example of a film that relies on genre conventions but often thwarts the expectations they arouse.

The same sort of equivocal qualities can be found in

Kane

’s relation to the classical Hollywood cinema. Even without specific prior knowledge about this film, we expect that, as an American studio product of 1941, it will obey guidelines of that tradition. In most ways, it does. We’ll see that desire propels the narrative, causality is defined around traits and goals, conflicts lead to consequences, time is motivated by plot necessity, and narration is objective, mixing restricted and unrestricted passages. We’ll also see some ways in which

Citizen Kane

is more ambiguous than most films in this tradition. Desires, traits, and goals are not always spelled out; the conflicts sometimes have an uncertain outcome; at the end, the narration’s omniscience is emphasized to a rare degree. The ending in particular doesn’t provide the degree of closure we would expect in a classical film. Our analysis will show how

Citizen Kane

draws on Hollywood narrative conventions but also violates some of the expectations that we bring to a Hollywood film.

Citizen Kane

In analyzing a film, it’s helpful to begin by segmenting it into sequences. Sequences are often demarcated by cinematic devices (fades, dissolves, cuts, black screens, and so on). In a narrative film, the sequences constitute the parts of the plot.

Most sequences in a narrative film are called

scenes.

The term is used in its theatrical sense, to refer to distinct phases of the action occurring within a relatively unified space and time. Our segmentation of

Citizen Kane

appears below. In this outline, numerals refer to major parts, some of which are only one scene long. In most cases, however, the major parts consist of several scenes, and each of these is identified by a lowercase letter. Many of these segments could be further divided, but this segmentation suits our immediate purposes.

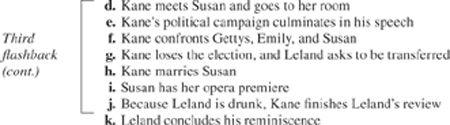

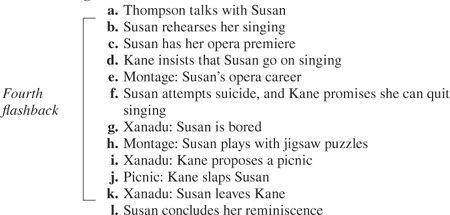

Our segmentation lets us see at a glance the major divisions of the plot and how scenes are organized within them. The outline also helps us notice how the plot organizes story causality and story time. Let’s look at these factors more closely.

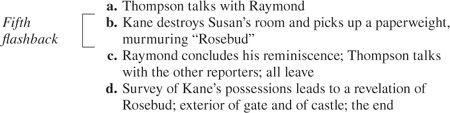

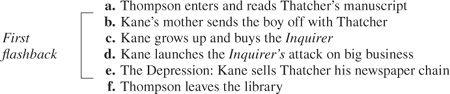

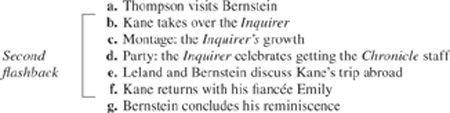

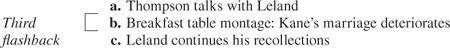

CITIZEN KANE:

PLOT SEGMENTATION

C. Credit title

- Xanadu: Kane dies

- Projection room:

- “News on the March”

- Reporters discuss “Rosebud”

- “News on the March”

- El Rancho nightclub: Thompson tries to interview Susan

- Thatcher library:

- Bernstein’s office:

- Nursing home:

- El Rancho nightclub:

- Xanadu: