B0041VYHGW EBOK (55 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

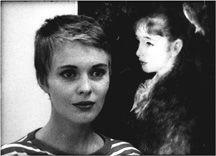

In

Breathless,

director Jean-Luc Godard juxtaposes Jean Seberg’s face with a print of a Renoir painting

(

4.106

).

We might think that Seberg is giving a wooden performance, for she simply poses in the frame and turns her head. Indeed, her acting in the entire film may seem flat and inexpressive. Yet her face and general demeanor are visually appropriate for her role, a capricious American woman unfathomable to her Parisian boyfriend.

4.106 Jean Seberg in

Breathless,

an inexpressive performance or an enigmatic one?

The context of a performance may also be shaped by the technique of film editing. Because a film is shot over a period of time, actors perform in bits. This can work to the filmmaker’s advantage, since these bits can be selected and combined to build up a performance in ways that could never be accomplished on the stage. If a scene has been filmed in several shots, with alternate takes of each shot, the editor may select the best gestures and expressions and create a composite performance better than any one sustained performance is likely to be. Through the addition of sound and the combination with other shots, the performance can be built up still further. The director may simply tell an actor to widen his or her eyes and stare offscreen. If the next shot shows a hand with a gun, we are likely to think the actor is depicting fear quite effectively.

Camera techniques also create a controlling context for acting. Film acting, as most viewers know, differs from theatrical acting. At first glance, that suggests that cinema always call for more underplaying, since the camera can closely approach the actor. But cinema actually calls for a stronger interplay between restraint and emphasis.

In a theater, we are usually at a considerable distance from the actor on the stage. We certainly can never get as close to the theater actor as the camera can put us in a film. But recall that the camera can be at

any

distance from the figure. Filmed from very far away, the actor is a dot on the screen—much smaller than an actor on stage seen from the back of the balcony. Filmed from very close, the actor’s tiniest eye movement may be revealed.

Thus the film actor must behave differently than the stage actor does, but not always by being more restrained. Rather, she or he must be able to

adjust to each type of camera distance.

If the actor is far from the camera, he or she will have to gesture broadly or move around to be seen as acting at all. But if the camera and actor are inches apart, a twitch of a mouth muscle will come across clearly. Between these extremes, there is a whole range of adjustments to be made.

“You can ask a bear to do something like, let’s say, ‘Stand up,’ and the bear stands up. But you cannot say to a bear, ‘Look astonished.’ So you have him standing up, but then you have to astonish him. I would bang two saucepans, or get a chicken from a cage, then shake it so it squawked, and the bear would think, ‘What was that?’ and ‘click’ I’d have that expression.”

— Jean-Jacques Annaud, director,

The Bear

Basically, a scene can concentrate on either the actor’s facial expression or on pantomimic gestures of the body. Clearly, the closer the actor is to the camera, the more the facial expression will be visible and the more important it will be (although the filmmaker may choose to concentrate on another part of the body, excluding the face and emphasizing gesture). But if the actor is far away from the camera, or turned to conceal the face, his or her gestures become the center of the performance.

Thus both the staging of the action and the camera’s distance from it determine how we will see the actors’ performances. Many shots in Bernardo Bertolucci’s

The Spider’s Stratagem

show the two main characters from a distance, so that their manner of walking constitutes the actors’ performances in the scene

(

4.107

).

In conversation scenes, however, we see their faces clearly, as in

4.108

.

4.107 In this long shot from

The Spider’s Stratagem,

the stiff, upright way in which the heroine holds her parasol is one of the main facets of the actress’s performance . .

4.108 … while in a conversation scene we can see details of her eye and lip movements.

Such factors of context are particularly important when the performers are not actors, or even human beings. Framing, editing, and other film techniques can make trained animals give appropriate performances. Jonesy, the cat in

Aliens,

seems threatening because his hissing movement has been emphasized by lighting, framing, editing, and the sound track

(

4.109

).

Editing makes it seem that the cat is reacting angrily to something within the scene where the shot appears, yet in reality it probably hissed at something quite different.

4.109 A cat “acting” in

Aliens.

As with every element of a film, acting offers an unlimited range of distinct possibilities. It cannot be judged on a universal scale that is separate from the concrete context of the entire film’s form.

Sandro and Claudia are searching for Anna, who has mysteriously vanished. Anna is Claudia’s friend and Sandro’s lover, but during their search, they’ve begun to drift from their goal of finding her. They’ve also begun a love affair. In the town of Noto, they stand on a church rooftop near the bells, and Sandro says he regrets giving up architectural design. Claudia is encouraging him to return to his art when suddenly he asks her to marry him.

She’s startled and confused, and Sandro comes toward her. She is turned away from us. At first, only Sandro’s expression is visible as he reacts to her plea “Why can’t things be simpler?”

(

4.110

).

Claudia twists her arms around the bell rope, then turns away from him, toward us, grasping the rope and fluttering her hand. Now we can see that she’s quite distraught. Sandro, a bit uneasy, turns away as she says anxiously, “I’d like to see things clearly”

(

4.111

).

4.110 A striking instance of frontality in

L’Avventura:

The characters alternate …

4.111 … turning their backs on the camera.

Brief though it is, this exchange in Michelangelo Antonioni’s

L’Avventura

(

The Adventure

) shows how the tools of mise-en-scene—setting, costume, lighting, performance, and staging—can work together smoothly. We’ve considered them separately in order to examine the contribution each one makes, but in any shot, they mesh. They unfold on the screen in space and time, fulfilling several functions.

Most basically, the filmmaker has to guide the audience’s attention to the important areas of the image. We need to spot the items important for the ongoing action. The filmmaker also wants to build up our interest by arousing curiosity and suspense. And the filmmaker tries to add expressive qualities, giving the shot an emotional coloration. Mise-en-scene helps the filmmaker achieve all these purposes.

How did Antonioni guide our attention in the Claudia–Sandro exchange? First, we’re watching the figures, not the railing behind them. Based on the story so far, we expect Sandro and Claudia to be the objects of interest. At other points in the film, Antonioni makes his couple tiny figures in massive urban or seaside landscapes. Here, however, his mise-en-scene keeps their intimate interchange foremost in our minds.

Consider the first image merely as a two-dimensional picture. Both Sandro and Claudia stand out against the pale sky and the darker railing. They’re also mostly curved shapes—heads and shoulders—and so they contrast with the geometrical regularity of the posts. In the first frame, light strikes Sandro’s face and suit from the right, picking him out against the rails. His dark hair is well positioned to make his head stand out against the sky. Claudia, a blonde, stands out against the railing and sky less vividly, but her polka-dot blouse creates a distinctive pattern. And considered only as a picture, the shot roughly balances the two figures, Sandro in the left half and Claudia in the right.