B0041VYHGW EBOK (75 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

5.77 John McTiernan’s

Die Hard.

5.78 In this busy scene from

Chunhyang,

our eye shuttles around the widescreen frame according to who is speaking, who is facing us, and who responds to the speaker.

The rectangular frame, while by far the most common, has not prevented filmmakers from experimenting with other image shapes within the rectangular frame. This has usually been done by attaching

masks

over either the camera’s or the printer’s lens to block the passage of light. Masks were quite common in the silent cinema. A moving circular mask that opens to reveal or closes to conceal a scene is called an

iris

. In

La Roue,

Gance employed a variety of circular and oval masks

(

5.79

).

In

5.80

, a shot from Griffith’s

Intolerance,

most of the frame is boldly blocked out to leave only a thin vertical slice, emphasizing the soldier’s fall from the rampart. A number of directors in the sound cinema have revived the use of irises and masks. In

The Magnificent Ambersons

(

5.81

),

Orson Welles used an iris to close a scene; the old-fashioned device adds a nostalgic note to the sequence.

5.79 Gance’s

La Roue.

5.80 Griffith’s

Intolerance.

5.81 Welles’s

The Magnificent Ambersons.

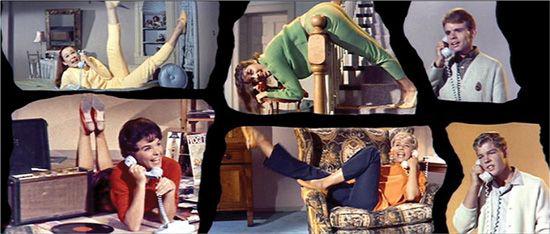

We also should mention experiments with

multiple-frame,

or

split-screen,

imagery. In this process, two or more images, each with its own frame dimensions and shape, appear within the larger frame. From the early cinema onward, this device has been used to present scenes of telephone conversations

(

5.82

).

Split-screen phone scenes were revived for phone conversations in

Bye Bye Birdie

(

5.83

)

and other 1960s widescreen comedies. Multiple-frame imagery is also useful for building suspense, as Brian De Palma has shown in such films as

Sisters.

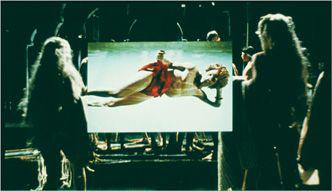

We gain a godlike omniscience as we watch two or more actions at exactly the same moment. Peter Greenaway used split screen more experimentally in

Prospero’s Books,

juxtaposing images suggested by Shakespeare’s

The Tempest

(

5.84

).

5.82 Philips Smalley’s 1913

Suspense

uses a three-way split screen.

5.83 Teenagers share the latest gossip in

Bye Bye Birdie

’s split-screen conversation.

5.84 The actor playing Ariel in

Prospero’s Books

hovers over the scene in a separate space.

As usual, the filmmaker’s choice of screen format can be an important factor in shaping the viewer’s experience. Frame size and shape can guide the spectator’s attention. It can be concentrated through compositional patterns or masking, or it can be dispersed by use of various points of interest or sound cues. The same possibilities exist with multiple-frame imagery, which must be carefully coordinated either to focus the viewer’s attention or to send it ricocheting from one image to another.

Whatever its shape, the frame makes the image bounded or limited. From an implicitly continuous world, the frame selects a slice to show us, leaving the rest of the space

offscreen.

If the camera leaves an object or person and moves elsewhere, we assume that the object or person is still there, outside the frame. Even in an abstract film, we cannot resist the sense that the shapes and patterns that burst into the frame come from somewhere.

Film aesthetician Noël Burch has pointed out six zones of offscreen space: the space beyond each of the four edges of the frame, the space behind the set, and the space behind the camera. It is worth considering how many ways a filmmaker can imply the presence of things in these zones of offscreen space. A character can aim looks or gestures at something offscreen. As we’ll see in

Chapter 7

, sound can offer potent clues about offscreen space. And, of course, something from offscreen can protrude partly into the frame. Virtually any film could be cited for examples of all these possibilities, but attractive instances are offered by films that use offscreen space for surprise effects.

In a party scene in William Wyler’s

Jezebel,

the heroine, Julie, is the main focus of attention until a man’s hand comes abruptly into the frame

(

5.85

–

5.88

).

The intrusion of the hand abruptly signals us to the man’s presence; Julie’s glance, the camera movement, and the sound track confirm our new awareness of the total space. The director has used the selective powers of the frame to exclude something of great importance and then introduce it with startling effect.

5.85 In

Jezebel,

the heroine, Julie, greets some friends in medium shot …