B0041VYHGW EBOK (72 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

With a matte painting, however, the actor cannot move into the painted portions of the frame without seeming to disappear. To solve this problem, the filmmaker can use a

traveling matte.

Here the actor is photographed against a blank, usually blue, background. In laboratory printing, the moving outline of the actor is cut out of footage of the desired background. After further lab work, the shot of the actor is jigsawed into the moving gap in the background footage. It is traveling mattes that present shots of Superman’s flight or of spaceships hurtling through space

(

5.51

).

The animated figures in

Who Framed Roger Rabbit?

(

5.52

)

were matted into liveaction footage shot separately.

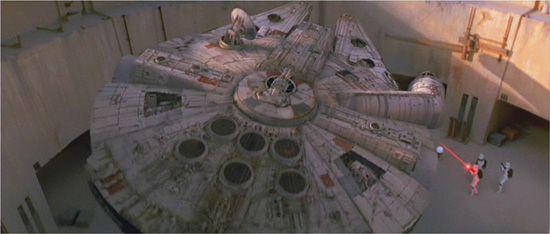

5.51 In

Star Wars: Episode IV—A New Hope,

the take-off of the

Millennium Falcon

was filmed as a model against a blue screen and matted into a shot of a building with imperial stormtroopers firing upward.

5.52 In

Who Framed Roger Rabbit?

a human director inhabits the same world as the cartoon characters starring in his film.

Before the perfecting of computer-generated imagery, traveling mattes were commonly used in all genres of mainstream cinema. Usually, they function to create a realistic-looking locale or situation. But they can also generate an abstract, deliberately unrealistic, image

(

5.53

).

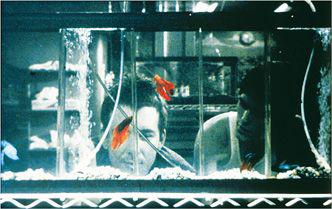

5.53 In

Rumble Fish,

a black-and-white film, Francis Ford Coppola uses traveling mattes to color the fish in an aquarium.

For many films, different types of special effects will be combined. The illustration from

The Fellowship of the Ring

in

5.50

includes a partial full-size set with an actor at the left, a miniature set in the middle ground, a matte painting of the background elements, and computer-animated waterfalls and falling leaves. A single shot of a science fiction film might animate miniatures or models through stop action, convey their movements by a traveling matte, and add animated ray bursts in superimposition while a matte painting supplies a background. For the train crash in

The Fugitive,

front and rear projection were used simultaneously within certain shots.

You may have noticed that superimpositions, projection process work, and matte work all straddle two general bodies of film techniques. These special effects all require arrangement of the material before the camera, so to some extent they are aspects of mise-en-scene. But they also require control of photographic choices (such as refilming and making laboratory adjustments) and affect perspective relations, so they involve cinematography as well. We have considered them here because, unlike effects employing models and miniatures, these effects are created through specifically photographic tricks. The general term for them,

optical effects,

suggests their photographic nature.

CONNECT TO THE BLOG

CGI can create spectacle, and some critics claim that the special effects make the story unimportant. We argue the opposite and talk about a film historian who backs us up in “Classical cinema lives! New evidence for old norms.”

With the rise of computer-generated effects, the fusion of mise-en-scene and cinematography became even more seamless. Digital compositing allows the filmmaker to shoot some action with performers and then add backgrounds, shadows, or movement that would previously have required photographed mattes, multiple exposures, or optical printing. In

Speed,

the audience sees a city bus leap a broken freeway. The stunt was performed on a ramp designed for the jump, and the highway background was drawn digitally as a matte painting

(

5.54

).

With the proliferation of specialized programs, computer-generated imagery (CGI) increasingly provides convincing effects that have all but replaced traditional optical printing. (See

“A Closer Look.”

)

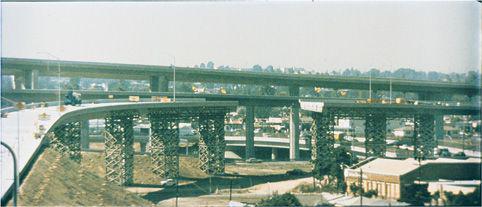

5.54 Computer-generated imagery created a gap in the freeway for the bus to leap in

Speed.

Like other film techniques, photographic manipulations of the shot are not ends in themselves. Rather, they function within the overall context of the film. Specific treatments of tonalities, speed of motion, or perspective should be judged less on criteria of realism than on criteria of function. For instance, most Hollywood filmmakers try to make their rear-projection shots unnoticeable. But in Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet’s

The Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach,

the perspective relations are yanked out of kilter by an inconsistent rear projection

(

5.55

).

Since the film’s other shots have been filmed on location in correct perspective, this blatantly artificial rear projection calls our attention to the visual style of the entire film.

5.55 The foreground plane of this shot from

The Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach

shows Bach, shot straight on, playing a harpsichord—yet the back-projected building behind him is shot from a low angle.

Similarly,

5.58

looks unrealistic unless we posit the man as being about three feet long. But director Vera Chytilova has used setting, character position, and deep focus to make a comic point about the two women’s treatment of men. Such trick perspective was designed to be unnoticeable in

The Lord of the Rings,

where an adult actor playing a three-foot-tall hobbit might be placed considerably farther from the camera than an actor playing a taller character, yet the two appeared to be talking face to face. (See

“A Closer Look,”

p. 184

) The filmmaker chooses not only how to register light and movement photographically but also how those photographic qualities will function within the overall formal system of the film.

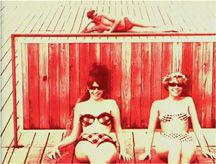

5.58 In

Daisies,

perspective cues create a comic optical illusion.

A CLOSER LOOK

FROM MONSTERS TO THE MUNDANE: Computer-Generated Imagery in

The Lord of the Rings

The films adapted from J.R.R. Tolkien’s trilogy

The Lord of the Rings (The Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers,

and

The Return of the King)

show how CGI can be used for impressive special effects: huge battle scenes, plausible monsters, and magical events. Less obviously, the films also indicate how CGI shapes many aspects of production, from the spectacular to the mundane.

CGI was used at every stage of production. In preproduction, a sort of animated storyboard (a

previz,

for “previsualization”) was made, consisting of

animatics,

or rough, computer-generated versions of the scenes. Each of the three previzes was roughly as long as each finished film and helped to coordinate the work of the huge staff involved in both digital and physical tasks.

During production of the three films, CGI helped create portions of the mise-en-scene. Many shots digitally stitched together disparate elements, blending full-size settings, miniature sets, and matte paintings (

5.50

). A total of 68 miniature sets were built, and computer manipulation was required in each case to make them appear real or to allow camera movements through them. Computer paint programs could generate matte paintings for the sky, clouds, distant cliffs, and forests that appeared behind the miniatures.

Rings

also drew on the rapidly developing capacity of CGI to create characters. The war scenes were staged with a small number of actual actors in costumes, while vast crowds of CGI soldiers appeared in motion alongside them. As happens for many films, new software programs were devised for

Rings.

A crucial program was Massive (for “Multiple Agent Simulation System in Virtual Environment”). Using motion-capture on a few

agents

(costumed actors), the team could build a number of different military maneuvers, assigning all of them to the thousands of crude, digitally generated figures. By giving each figure a rudimentary artificial intelligence—such as the ability to see an approaching soldier and identify it as friend or foe—Massive could generate a scene with figures moving differently from each other

(

5.56

).

5.56 Vast crowds of soldiers with individualized movements were generated by the Massive software program for

The Two Towers.

The monsters encountered by the characters during their quest were more elaborately designed and executed than the troops. A detailed three-dimensional model of each creature was captured with a new scanning wand that could read into recesses and folds to create a complete image from all angles. A new system, Character Mapper, captured motion from an actor, then adjusted the mass and musculature to imaginary skeletons. In the cave-troll sequence, the large, squat creature swings its limbs and flexes its muscles in a believable fashion.

Most of the speaking characters (with the important exception of the skeletal Gollum) were played by actors, but even here CGI was used. The main characters had digital look-alikes who served as stunt doubles, performing actions that were dangerous or impossible. In the cave-troll fight, the actors playing Legolas, Merry, and Pippin were all replaced by their digital doubles when they climbed or jumped on the troll’s shoulders. A requirement specific to this story was the juxtaposition of full-size actors playing threefoot-tall hobbits with other characters considerably taller than themselves. The size difference was often created during filming by using small doubles or by placing the hobbits farther from the camera in falseperspective sets.

In many cases, CGI created the kinds of special effects formerly generated on an optical printer. In

The Fellowship of the Ring,

such effects include Gandalf’s fireworks, the flood at the Fords of Bruinen, the avalanche that hits the Fellowship on the mountain pass, and the flaming Eye of Sauron.

Cinematography also depended on CGI. For the cave-troll scene, director Peter Jackson donned a virtual-reality helmet and planned camera positions by moving around a virtual set and facing a virtual troll. The camera positions were motion-captured and reproduced in the actual filming of the sequence—which has a rough, handheld style quite different from the rest of the scenes.

In postproduction, animators erased telephone poles in location shots and helicopter blades dipping into the aerial shots of the Fellowship’s voyage across mountains. Specialized programs added details, such as the ripples in the water in the Mirror of Galadriel.

Perhaps most important, digital grading altered the color of shots, giving each major location a distinctive look. Rivendell’s scenes are in autumnal tones, while the early scenes in the Shire were given a yellow glow that enhanced the sunshine and green fields. The grading also utilized an innovative program, 5D Colossus, which allowed artists to adjust the color values of individual elements within a shot. Thus in the Lórien scene in which Galadriel shows Frodo her mirror, she glows bright white, contrasting with the deep blue tones of Frodo’s figure and setting

(

5.57

).

Thanks to digital grading, CGI techniques can go beyond the creation of imaginary creatures and large crowds to shape the visual style of an entire film.

5.57 In

The Fellowship of the Ring,

selective digital color grading makes one figure bright white while the rest of the scene has a uniform muted blue tone.