B0041VYHGW EBOK (69 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

A long-focal-length lens also affects subject movement, flattening depth. Thus a figure moving toward the camera takes more time to cover what seems to be a small distance. The running-in-place shots in

The Graduate

and other films of the 1960s and 1970s were produced by lenses of very long focal length. In

Tootsie,

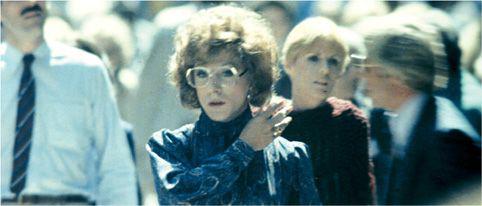

the introduction of Michael Dorsey disguised as Dorothy Michaels occurs in a lengthy telephoto shot in order for us to recognize his altered appearance and to notice that none of the people around him finds “her” unusual

(

5.26

–

5.28

).

5.26 In

Tootsie,

Dorothy becomes visible among the crowd at a considerable distance from the camera …

5.27 … and after taking 20 steps seems only slightly closer until …

5.28 … “she” finally grows somewhat larger, after a total of about 36 steps.

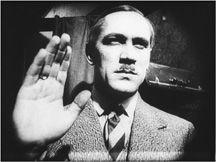

Lens length can distinctly affect the spectator’s experience. For example, expressive qualities can be suggested by lenses that distort objects or characters. We tend to see the man in

5.29

as looming, even aggressive. Moreover, choice of the lens can make a character or object blend into the setting (

5.26

) or stand out in sharp relief (

5.29

). Filmmakers may exploit the flattening effects of the long-focal-length lens to create solid masses of space

(

5.30

),

as in an abstract painting.

5.29 In Ilya Trauberg’s

China Express,

a wide-angle lens creates foreground distortion.

5.30 In

Eternity and a Day,

a long lens makes the beach and sea appear as two vertical blocks.

“I tend to rely on only two kinds of lenses to compose my frames: very wide angle and extreme telephoto. I use the wide angle because when I want to see something, I want to see it completely, with the most detail possible. As for the telephoto, I use it for close-ups because I find it creates a real ‘encounter’ with the actor. If you shoot someone’s face with a 200-millimeter lens, the audience will feel like the actor is really standing in front of them. It gives presence to the shot. So I like extremes. Anything in between is of no interest to me.”

— John Woo, director

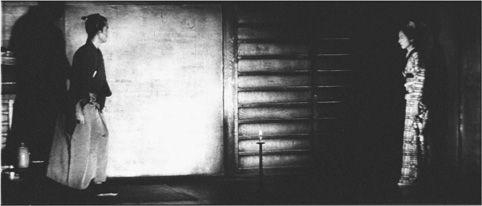

A director can use lens length to surprise us, as Kurosawa does in

Red Beard.

When the mad patient comes into the intern’s room, a long-focal-length lens filming from behind him initially makes her seem to be quite close to him

(

5.31

).

But a cut to a more perpendicular angle shows that the patient and the intern are actually several feet apart and that he is not yet in danger

(

5.32

).

5.31 In Kurosawa’s

Red Beard,

the mad patient in the background seems threateningly to approach the intern …

5.32 … until a cut reveals that she is across the room from him.

There is one sort of lens that offers the director a chance to manipulate focal length and to transform perspective relations during a single shot. A

zoom lens

is optically designed to permit the continuous varying of focal length. Originally created for aerial and reconnaissance photography, zoom lenses gradually became a standard tool for newsreel filming. It was not, however, the general practice to zoom during shooting. The camera operator varied the focal length as desired and then started filming. In the late 1950s, however, the increased portability of cameras led to a trend toward zooming while filming.

Since then, the zoom has sometimes been used to substitute for moving the camera forward or backward. Although the zoom shot presents a mobile framing, the camera remains fixed. During a zoom, the camera remains stationary, and the lens simply increases or decreases its focal length. Onscreen, the zoom shot magnifies or demagnifies the objects filmed, excluding or including surrounding space, as in

5.33

and

5.34

, from Francis Ford Coppola’s

The Conversation.

The zoom can produce interesting and peculiar transformations of scale and depth, as we shall see when we examine Michael Snow’s

Wavelength.

5.33 In the opening of

The Conversation,

a long, slow zoom-in arouses considerable uncertainty about its target …

5.34 … until it finally centers on a mime and our protagonist, surveillance technician Harry Caul.

The impact that focal length can have on the image’s perspective qualities is dramatically illustrated in Ernie Gehr’s abstract experimental film

Serene Velocity.

The scene is an empty corridor. Gehr shot the film with a zoom lens, but he did not zoom while filming the shot. Instead, the zoom permitted him to change the lens’s focal length between takes. As Gehr explains,