B004R9Q09U EBOK (25 page)

Authors: Alex Wright

Jefferson’s endorsement of Linnaean classification would not mark the last time the gentleman from Monticello influenced the course of information science. Jefferson’s legacy as a naturalist has long since faded in the shadow of his great contributions as a statesman—as president, vice president, and author of the Declaration of Independence and the Virginia Statute of Religious Freedom. Jefferson, however, prided himself first and foremost on being a naturalist. He is said to have considered it a higher honor to have been named president of the American Philosophical Society than to have been elected vice president of the United States. “Nature intended me for the tranquil pursuits of science,” he once wrote, “by rendering them my supreme delight.”

Almost 30 years after he left Paris, Jefferson would again make a final grand gesture with lasting effects on the structure of information systems. In the autumn of 1814 (after he had retired from the presidency), the British sacked Washington, destroying much of the federal government’s physical infrastructure, including its nascent library. Just as previous wars had left burning libraries in their wake (see also Alexandria, the Aztecs, and the Chinese emperor Shi Huangdi), the British had tried to burn down the young nation’s intellectual capital.

As Washington recovered from the British attack, Jefferson

penned a letter to his longtime friend Samuel H. Smith, then serving as chairman of the congressional Library Committee. Jefferson offered his entire personal library as a replacement for the Library of Congress.

Jefferson had amassed an enormous collection, much of it during his tenure in Paris, where he scoured local bookstores and established standing orders with book dealers in Amsterdam, Frankfurt, Madrid, and London. “[S]uch a collection was made as probably can never again be effected,” wrote Jefferson. By 1814 Jefferson’s library ranked among the largest private book collections in the world: 6,500 volumes, consisting of “what is chiefly valuable in science and literature generally, [it] extends more particularly to whatever belongs to the American statesman. In the diplomatic and parliamentary branches, it is particularly strong.” His collection embodied a monumentally important transfer of knowledge between continents.

Fifty years in the making, Jefferson’s library at Monticello constituted a formidable intellectual warehouse. Among the volumes Jefferson prized most were Milton’s

Paradise Lost

, Sir Isaac Newton’s

Optics

, works by Thomas More and Alexander Pope, numerous histories, and a 10-volume gardener’s dictionary. He also had 20 copies of the Bible and two of the Koran.

Congress accepted Jefferson’s offer but not without a bout of partisan intellectual wrangling. “The grand library of Mr. Jefferson will undoubtedly be purchased,” wrote the

Boston Gazette

, “with all its finery and philosophical nonsense.” Massachusetts Rep. Cyrus King, in high Puritan dudgeon, insisted that the collection be purged of “all books of an atheistical, irreligious, and immoral tendency.” After a bout of acrimonious debate, the gentleman from Massachusetts eventually withdrew his objection. In this small gesture he may well have influenced the course of history.

Finally, Jefferson loaded his library on 10 wagons packed with pine bookcases for the trip from Monticello to Washington. “I hope it will not be without some general effect on the literature of our country,” he later wrote.

While Jefferson’s library was impressive in size, far more interesting was its complex semantic structure. At the time, libraries typically

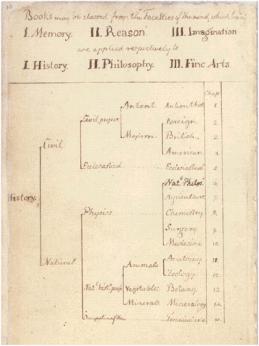

arranged their books by alphabetical order. In describing his own collection, Jefferson explained to Librarian of Congress George Watterston that he had abandoned the popular convention and chosen as his philosophical reference point “Lord Bacon’s table of science,” a hierarchical classification scheme that divided the whole of human knowledge into three broad categories: Memory (history), Reason (philosophy), and Imagination (fine arts).

A page from Thomas Jefferson’s 1783 Library Catalog. Reproduced by permission of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, MA.

(See

Appendix B

for the full classification scheme.)

Jefferson modified the scheme to suit his own needs, developing a permuted classification system that would sometimes classify books by subject, sometimes by chronology, “& sometimes a combination of both.” It is worth noting that Jefferson’s scheme, like so many other hierarchical classification systems, extends five levels deep, echoing the structure of ancient folk taxonomies.

Like Aristotle, Jefferson had created a great personal library, cataloged it, and then donated it as the foundation for a budding national library. And just as Aristotle’s own library catalog, coupled with his writings on natural classification, would reverberate long after his passing, Jefferson exerted a similar influence on the intellectual underpinnings of the United States of America. He rarely receives the credit he deserves as a forefather of information science. Jefferson’s decisions—embracing Linnaean taxonomy and Baconian empiricism over the competing theories of Buffon and others—set the stage for the information architecture of the young republic.

A library book … is not, then, an article of mere

consumption but fairly of capital.

Thomas Jefferson to James Madison, September 1821

In 1909 a Boston gentleman named Edmund Lester Pearson remarked on the proliferation of a new apparatus fast becoming a fixture in library reading rooms: the card catalog. “As these cabinets of drawers increase in number,” he wrote, “it seems as if the old joke about the catalogues of the Boston Public Library and Harvard University meeting on Harvard Bridge might become literally true.”

1

The image of catalogs colliding seems an apt metaphor for the bibliographical boom that was sweeping the library world. The Industrial Revolution had spawned more than factories, textile mills, and Marxists. It had also transformed the economy of the written word. New steam-driven mechanical presses were stamping out thousands of pages an hour, powering the rise of great publishing houses that turned out books and newspapers in mass quantities, catering to a growing market of newly literate readers (thanks to another industrial innovation: public education). Novels, magazines, pamphlets, and all manner of printed artifacts sluiced through the literary mills. Books became industrial products, even commodities.

Libraries struggled to keep pace. Before the nineteenth century was out, they too would find themselves transformed into industrialized institutions. Preindustrial libraries had been little more than gen

teel reading rooms, staffed by learned gentleman curators who looked after modest collections of hand-bound leather volumes. Some university libraries employed a “professor of books,” a descendent of the medieval

armarius

, to help guide the bookish student, but there were few “librarians” in the modern sense. Public libraries were all but unheard of; most libraries belonged to universities, learned societies, or private citizens (although some cities boasted private subscriptionbased libraries for upper-crust society men, like the Boston Athenæum). Those few libraries with collections large enough to warrant a catalog usually maintained an alphabetical list of holdings in leather-bound book catalogs. These were typically little more than inventories, designed to keep track of the collection and allow readers to locate a specific book on the shelf.

The industrialization of the printing press and the rise of a growing literate populace exerted severe pressures on these formerly placid institutions. In 1800 the library of the British Museum (precursor to the modern British Library) held 48,000 volumes. By 1833 the collection had quintupled to more than a quarter million.

2

As collections grew, libraries found it increasingly difficult to maintain their old leather-bound catalogs. Faced with rapidly growing collections, libraries inevitably started to mirror the industrial methods that were causing the disruption. Faced with processing backlogs and bulging catalogs, they succumbed to the inexorable logics of industrialization, seeking operating efficiencies, standardizing roles, and normalizing their data. As the nineteenth century progressed, the effects of industrialization would transform the enterprise of the library from a bookman’s craft into a bibliographical assembly line.

Today, if you walk into almost any library, you will find what is still, at its core, a nineteenth-century institution. The primary feature of most libraries is still a set of long shelves populated by industrially printed books, organized according to a proscribed hierarchical system of call numbers, maintained by specially trained workers laboring in a highly regimented organizational system. The old card catalog may have given way to computer terminals, but the underlying organizational and ontological structures of the modern library have hardly changed at all. Librarians still follow cataloging practices that

originated in the 1850s; library organizations are notoriously top-down, hierarchical, and process-oriented operations. And like steel mills, factories, secondary schools, and other institutional offspring of the nineteenth century, libraries are struggling to reinvent themselves in a postindustrial age.

To appreciate the legacy of the industrial library—and why it has proved such a durable fixture even in our digital age—we must look to where the revolution began: Great Britain.

In 1831 the British Museum hired Anthony Panizzi as its new assistant keeper of printed books. By this time there were already early rumblings of the industrial printing boom. Books were streaming in and so were readers. In 1759 the library had attracted five visitors a month. A century later there were 180 visitors a day. Changing conditions seemed to demand a radical rethinking of the library operation. Fortunately for the British Museum, the man they had just hired was no stranger to radical causes.

A lawyer by training, Panizzi had fled Italy after escaping arrest for his membership in a secret revolutionary group struggling to liberate Italy from the grips of the Austrian empire. After a dramatic getaway, Panizzi traveled all over Europe before landing in England. Although he would spend the rest of his life in exile, Panizzi never lost his revolutionary disposition. The fiery young Italian appears to have struck quite a figure among his staid British colleagues. One of his early biographers, Louis Fagan, describes him as “tall, thin and of dark complexion; in temper somewhat hot and hasty, but of calm and even judgment. … He must have been most diligent in his pursuit of knowledge, losing no opportunity of study, for he is described as constantly engaged in reading, even while walking from his house to the office.”

3

In the years that followed, the energetic Panizzi would stir up more than his share of trouble with the British establishment, bringing his revolutionary zeal to bear in forming a new, highly politicized philosophy of librarianship and leaving behind a legacy of committed, socially engaged librarianship that still resonates today.

By the time Panizzi arrived, the British Museum’s library catalog was in desperate need of an overhaul. In 1810 the printed catalog had run to 7 volumes; when Panizzi took over in 1831, it had bulged to 48

volumes, overflowing with inserts and scribbled errata. When the museum’s commissioners asked their young hire to begin work on revising the catalog, they may have thought they were assigning a rote task to a junior employee. But Panizzi, the exiled radical, surprised everyone by coming back to propose the most ambitious revision to the catalog since Callimachus.

Panizzi saw the incoming flurry of books as more than just an inventory problem. He saw the makings of a larger opportunity for the cause of education and literacy. He wanted to reconceive the catalog in a new populist spirit. He began by introducing a subject catalog. While great libraries of the past had cataloged books by subject, no one had ever tried to create Panizzi’s kind of comprehensive classification. He created a new schedule of tiered subject headings, a carefully constructed classification system that reflected the universalist ambitions of the British Empire at the height of its power. “Some would argue [the subject headings] were too ambitious,” writes Elaine Svenonius, “that there was no need to construct elaborate Victorian edifices since jerrybuilt systems could meet the needs of most users most of the time.”

4

But the introduction of subject headings at all marked a major philosophical step toward opening up the catalog to a broader audience.