B004R9Q09U EBOK (29 page)

Authors: Alex Wright

The effort met with early success, even attracting a healthy mail

order business, in which users submitted search queries for a fee (27 francs per 1,000 cards retrieved). The service attracted more than 1,500 requests a year on subjects ranging from boomerangs to Bulgarian finance. But by 1924 the Belgian government had lost patience with the project, especially after the newly formed League of Nations chose Geneva over Brussels as its headquarters—thus robbing the

Mundaneum

of one of its primary raisons d’etre. Otlet had to relinquish his original location, moving the

Mundaneum

to a succession of smaller quarters, even landing briefly, ignominiously, in a parking garage. After a series of fiscal struggles and management missteps, Otlet finally faced the difficult but unavoidable choice of shutting down the operation in 1934. A few years later Nazi troops stormed in and carted it all away, to make way for an exhibition of Third Reich art.

“L’organisation mondiale du Travail intellectuel,” from Otlet’s

Traité de documentation

(1934).

After Otlet’s death in 1944, what survived of the original

Mundaneum

was left to languish in an old anatomy building of the Free University in the

Parc Leopold

, all but forgotten for three decades, until Boyd Rayward found his way into Otlet’s old office. Over

the ensuing half-century, more than 70 tons of its original contents were destroyed. Finally, in the mid-1990s a group of volunteers began resurrecting Otlet’s original vision, hoping to preserve and refurbish the original

Mundaneum

. In 1996 the new

Mundaneum

opened in Mons, Belgium, to preserve Otlet’s legacy and his vision of the “Universal Book.” While today’s

Mundaneum

serves primarily as a museum and learning center rather than as a working incarnation of Otlet’s original plan, the new institution does an admirable job of perpetuating his legacy and reminding us of Otlet’s premonitory vision of a worldwide networked information environment.

In a bitter irony, the

Mundaneum

’s 1934 closure coincided almost exactly with the publication of Otlet’s masterwork, the

Traité de documentation

, a manifesto crystallizing 40 years’ worth of writing and research into the possibilities of networked information structures. Rayward describes the

Traité

as “perhaps the first systematic, modern discussion of general problems of organising information.” With the faceted philosophy of the UDC as backdrop, the

Traité

posited a universal “law of organization” declaring that no document could ever be fully understood by itself, but that its meaning becomes clarified through mining its relationship with other documents. “[A]ll bibliological creation,” he said, “no matter how original and how powerful, implies redistribution, combination and new amalgamations.”

4

While that sentiment may sound postmodernist in spirit, Otlet was no semiotician; he simply believed that documents could best be understood as three-dimensional things, with the third dimension being their social context: their relationship to place, time, language, as well as other readers, writers, and topics. Otlet believed in the possibility of empirical truth, or what he called “facticity”—a property that emerged over time, and through the ongoing collaboration between readers and writers. In Otlet’s world each user would leave an imprint, a trail, which would then become part of the explicit history of each document.

Vannevar Bush and Ted Nelson would later voice strikingly similar ideas about the notion of associative “trails” between documents. Distinguishing Otlet’s vision from the later ideas of Bush, Nelson, and Berners-Lee is the conviction—long since fallen out of favor—in

the possibility of a universal subject classification working in concert with the mutable social forces of scholarship. Otlet’s vision suggests an intellectual cosmos illuminated by both objective classification and the direct influence of readers and writers: a system simultaneously ordered and self-organizing and endlessly reconfigurable by the individual reader.

Jorge Luis Borges’s fictional Library of Babel was a place containing “all the possible combinations of the twenty-odd orthographical symbols … the translation of every book in all languages, the interpolations of every book in all books.” For Borges the universal library was a literary conceit. For Otlet it was an achievable dream: an “edifice containing all the books and the information together with all the resources of space needed to record and manage them.” Otlet also recognized the practical importance of “search and retrieval performed by an appropriately qualified permanent staff.” Substitute the word “Google” for “permanent staff,” and Otlet’s vision starts sounding a lot like the World Wide Web.

While it would be an exaggeration to claim that Otlet exerted any direct influence on the later development of the Web, it would be no exaggeration to say that he anticipated many of the problems bedeviling the Web today: the explosion of published information, the limitations of fixed documents, and the opportunities for scholarship that open up when readers can penetrate the “meta” content surrounding a document to get at the contents inside. In the Web’s current incarnation, individual “authors” (including both individuals and institutions) exert direct control over fixed documents. Each document is essentially a fait accompli, with its own self-determined set of relationships to other documents. It takes a meta-application like Google or Yahoo! to discover the broader relationships between documents (usually through some combination of syntax, semantics, and reputation). But those relationships, however sophisticated the algorithm, remain largely unexposed to the end user, never becoming an explicit part of the document’s history. In Otlet’s vision those pathways constituted vital information, making up the third dimension of social context that made his system so potentially revolutionary.

Would Otlet’s Web have turned out any differently? We may yet

find out. The explosive growth of socially driven Web applications—like

secondlife.com

,

MySpace.com

,

Flickr.com

, and

del.icio.us

—suggest that many Web users are clamoring for social context, relying less on formal ontologies than on socially constructed information spaces. At the same time, many of these social systems suffer from problems of fluidity and instability; they are moving targets. Otlet’s vision holds out a tantalizing possibility: marrying the determinism of a top-down classification system with the bottom-up relativism of emergent social networks.

In Otlet’s last book,

Monde

, he articulates a final vision of the great

réseau

that might as well serve as his last word:

Everything in the universe, and everything of man, would be registered at a distance as it was produced. In this way a moving image of the world will be established, a true mirror of his memory. From a distance, everyone will be able to read text, enlarged and limited to the desired subject, projected on an individual screen. In this way, everyone from his armchair will be able to contemplate creation, as a whole or in certain of its parts.

While Otlet’s

Mundaneum

vanished like a mirage in the wake of World War II, a similarly ambitious vision of automated information retrieval was percolating across the Atlantic. In 1945 Vannevar Bush

5

published his seminal essay, “As We May Think,” in

The Atlantic Monthly

, sketching the contours of a fictional machine dubbed the Memex. Bush envisioned the device as a scholar’s workstation, providing access to large collections of documents stored on microfilm, allowing users to read, write, and annotate documents and—most importantly—to forge “associative trails” between them. Written in the age before digital computers, Bush’s essay painted a provocative and inspiring vision of an entirely new kind of machine.

Bush’s imaginary device captured the popular imagination right away. Excerpts and feature stories appeared in the

Associated Press

,

Life

, the

New York Times,

and elsewhere. Even after the initial swell of popular interest subsided, the ideas that Bush suggested would per

colate for decades. Today, computer scientists still genuflect reflexively to the inspiration of the Memex. Yet Bush’s vision remains surprisingly misunderstood, even by many of those who claim to embrace it. “It is strange that [‘As We May Think’] has been taken so to heart in the field of information retrieval,” writes Ted Nelson, “since it runs counter to virtually all work being pursued under the name of information retrieval today.”

7

Indeed, Bush’s essay in some ways reads as an indictment of everything that was about to go wrong with the computer industry.

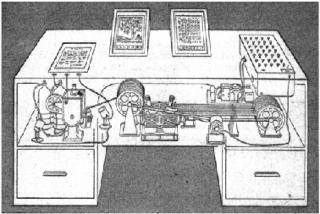

Alfred D. Cimi’s rendering of the Memex in

Life

, September 10, 1945. Caption read: “MEMEX in the form of a desk would instantly bring files and material on any subject to the operator’s fingertips. Slanting translucent viewing screens magnify supermicrofilm filed by code numbers. At left is a mechanism which automatically photographs longhand notes, pictures and letters, then files them in the desk for future reference.”

6

While Bush’s essay now ranks as one of the canonical texts in computer science—inspiring generations of programmers and, as we shall see later in this chapter, directly influencing the evolution of the World Wide Web—the essay’s fame has in some ways overshadowed

Bush’s real intellectual legacy. “As We May Think” has cast such a long historical shadow that it now obscures much of Bush’s subsequent thinking and writing about the Memex, most of which now languishes in out-of-print obscurity. Bush would have no doubt recognized the bitter irony that most of his best writing is nowhere to be found on the Web, persisting only on the shelves of the old-fashioned physical libraries he spent much of his career trying to automate out of existence.

The deeper history of the Memex suggests a vision far more provocative than the original microfilm-based device he proposed in 1945. It is not just a story about an innovative idea for managing documents; it is a parable of how a great American engineer turned into cautionary prophet, warning against the influence of corporations on the trajectory of computer science, of the predominance of mathematical and logical models of computing over what he considered a more natural biological approach, and even, in Bush’s later writing, espousing provocative and sometimes controversial views on topics like ESP and the coevolution of human brains and machines. None of these themes would emerge until after the publication of “As We May Think.”

To understand the broader implications of the Memex, we need to begin by looking at Bush’s earlier experiences in the real world of nonimaginary machines. By the time he started musing about the Memex in the late 1930s, Bush had already designed a series of analog computers dating back to the 1920s, including the successful Differential Analyzer, a room-sized machine that employed a complicated array of gears, cams, and shafts to solve complex mathematical problems like differential equations. While other engineers were probing the possibilities of computing with electrical circuits, Bush took a different, almost nineteenth-century, approach, modeling his invention after Charles Babbage’s famous gear-driven Difference Engine. Bush’s computer did not rely on electrical circuits to perform calculations; instead it only used electricity to power a set of gear shafts that did the actual math. The thing was a kind of turbocharged abacus.

In 1933 Bush published a long-overlooked essay in

Technology Review

entitled “The Inscrutable ’Thirties.” Until this point in his ca

reer, he had been a prolific inventor and engineer, publishing a string of dry technical papers and patent filings. Now, he began to carve out a more ambitious role for himself as a kind of technological Jeremiah, forecasting the future trajectory of technology by trying to identify long-term predictive trends. Bush scholars Nyce and Kahn describe the essay as “a literary satire, an ironic description of the present seen from an imaginary future when an appreciation of the ‘difficulties surrounding a former generation’ would lead the reader to marvel that so much was accomplished with so little.”

8

Bush conjures up the character of a harried professor of the 1930s, contending with, among other things, a slow-moving car and a primitive environment for conducting scholarly research: