Baseball's Hall of Fame or Hall of Shame (15 page)

Also, like Fisk, Carter finished in the top five in the league MVP voting twice, and in the top ten another two times. Like Fisk, he was selected to the All-Star Team 11 times. In addition, Carter was an excellent defensive receiver, with three Gold Gloves to his credit, as opposed to just one for Fisk. He led the league five times in assists, and six straight years in putouts.

There are three possible explanations as to why it took Carter longer to get elected to Cooperstown. The first lies in the fact that, due to his greater longevity, Fisk’s career numbers are slightly superior to Carter’s. Secondly, Fisk remained an effective offensive player for most of his career, becoming a liability at the plate in just his final two seasons. Meanwhile, the image that many people have of Carter towards the end of his career is probably that of someone who was hanging on to the very end. He failed to hit more than 11 home runs or drive in more than 46 runs in any of his final five seasons. Perhaps even more telling, though, is the fact that many members of the press (the people that have the final say as to who goes into the Hall) were put off somewhat by what they perceived to be Carter’s constant posturing for media and fan attention during his playing days. He took every opportunity he could to talk to the press, and he enjoyed being the center of attention. This alienated some of his teammates in Montreal, and irked many outsiders as well.

Probably more than anything else, this is what also kept him out of the Hall of Fame for three or four years, because Carter should have been viewed in much the same light as Fisk. He was a very good player whose selection was a pretty good one. However, like Fisk, he should be viewed as someone who was not an obvious selection.

Ernie Lombardi

With the exception of Gabby Hartnett, Ernie Lombardi was probably the National League’s best catcher during the first half of the 20th century. Playing primarily for the Cincinnati Reds and New York Giants, Lombardi succeeded Hartnett during the late 1930s as the league’s top receiver. He won the batting title in 1938, with an average of .342, and was voted the league’s Most Valuable Player that year. During his career, he batted over .300 ten times, surpassing the .330-mark five times. He was clearly the N.L.’s best catcher from 1936 to 1942, and was selected to the All-Star Team seven times.

However, with the possible exception of the 1938 and 1940 seasons, Lombardi was never considered to be the best catcher in baseball (Hartnett and Dickey were both rated above him for most of his career). In addition, while he was an excellent hitter, Lombardi was far from a complete player. During his career, he was well known for being the slowest player in the game and a completely immobile, below-average defensive catcher.

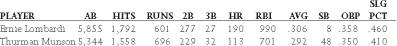

Because he was so slow, he never scored more than 60 runs in any season. Although he batted over .300 ten times, he never had as many as 500 at-bats in any season, and he topped 400 plate appearances only four times. Primarily because of his limited number of at-bats, Lombardi never knocked in more than 95 runs in a season, and he compiled as many as 80 RBIs only twice. If his numbers are viewed alongside those of Thurman Munson, who is not in the Hall of Fame, it appears that the two catchers were fairly comparable as offensive players:

While, on the surface, Lombardi’s statistics seem more impressive than Munson’s, they really were not. To begin with, Lombardi played during the 1930s and 1940s, in much more of a hitter’s era than when Munson played, during the 1970s. Lombardi also had the advantage of spending most of his career playing in good hitter’s parks in Cincinnati’s Crosley Field and New York’s Polo Grounds. Meanwhile, Munson had to play half his games in Yankee Stadium, which has always been an extremely difficult ballpark for righthanded batters.

Furthermore, on Munson’s behalf, he had more than 500 at-bats in seven of his ten seasons, something Lombardi failed to do even once. He had three straight seasons in which he knocked in over 100 runs (something else Lombardi never did) and batted over .300. Munson batted over .300 five times during his career and scored more than 80 runs three times. In addition, prior to being slowed by shoulder and knee problems that plagued him during the latter stages of his career, Munson was an excellent defensive catcher, winning three Gold Gloves. He was a superb handler of pitchers and, as captain of the Yankees, was a true team leader. He was selected to the A.L. All-Star Team seven times, was named the league’s MVP in 1976, and finished in the top 10 in the voting two other times. He was the top catcher in the American League from 1973 to 1976, and the best in baseball in 1976 and, perhaps, in 1975 as well. In his prime, he was considered to be at least the equal of his Boston counterpart, Carlton Fisk, who is in the Hall of Fame.

All this is not to suggest that Thurman Munson should be elected to the Hall of Fame. Frankly, as good as he was, his career was too short, and his career numbers are not impressive enough. But, while Ernie Lombardi was a slightly better hitter, Munson was a better all-around player who deserves to be in Cooperstown as much as Lombardi. Unfortunately, when the Veterans Committee elected Lombardi in 1986, it was not a very good decision.

Rick Ferrell

The Veterans Committee’s selection of Rick Ferrell in 1984 was an even worse one than it would make two years later with Lombardi. It is one of those that just leaves you scratching your head and wondering to yourself, “What were they thinking?” Ferrell, who caught for the St. Louis Browns, Boston Red Sox, and Washington Senators during his 18-year career, has, by far, the worst offensive numbers of any catcher in the Hall of Fame who played after the Deadball Era. Let’s take a look at his statistics:

That’s right—28 home runs, 734 RBIs and 687 runs scored in over 6,000 career at-bats! Add to that the fact that Ferrell had only six seasons in which he had as many as 400 at-bats (like Lombardi, he never had 500 in a season), never knocked in more than 77 runs in a season, and never scored more than 67, and what you have essentially is a nice player who was among the better catchers of his era. However, he was always rated far behind both Bill Dickey and Mickey Cochrane in the American League during his career, and he probably doesn’t even rank among the 25 or 30 best catchers in the history of the game. Yet, Ferrell was well-liked and had friends on the Veterans Committee. Therefore, he was able to get elected to the Hall of Fame.

Roger Bresnahan/Ray Schalk

The selections of Bresnahan and Schalk, both completely unwarranted, are extreme examples of the politics involved in the Hall of Fame elections.

Roger Bresnahan played primarily with the New York Giants, St. Louis Cardinals, and Chicago Cubs at the turn of the last century. He was the Giants’ regular catcher from 1903 to 1908. During that time, he established a very good relationship with Giants manager John McGraw, one of the most influential men in the game. He became one of McGraw’s favorites, eventually working under him as one of the team’s coaches. During his playing career, Bresnahan stole 212 bases and finished with a very respectable .386 on-base percentage. However, he also finished with just under 4,500 at-bats, 1,252 hits, 530 runs batted in, 682 runs scored, and a .279 batting average—hardly Hall of Fame numbers.

Ray Schalk spent virtually his entire 18-year career with the Chicago White Sox, and was a member of the 1919 squad that was accused of throwing the World Series. He was an excellent receiver and handler of pitchers, but was a relatively weak hitter, batting only .253, hitting only 11 home runs, driving in just 594 runs, and scoring only 579 others in just over 5,300 career at-bats. He never batted any higher than .282, knocked in more than 61 runs, or scored more than 64 runs during his 18 seasons, and he finished with a feeble .316 slugging percentage.

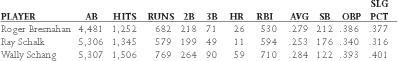

If you look at the numbers of both players alongside those of Wally Schang, a contemporary of Schalk who caught for the Philadelphia A’s, Boston Red Sox, New York Yankees, and St. Louis Browns during a career that spanned the years 1913-1931, it becomes even more difficult to understand why Bresnahan and Schalk were elected:

In virtually the same number of at-bats, Schang, who is not in the Hall of Fame, finished well ahead of both men in every offensive category, except stolen bases. In addition, he was considered to be a fine defensive catcher, and he played on five pennant-winning teams and three world champions in Philadelphia and New York.

Why, then, are Bresnahan and Schalk in, while Schang isn’t? In Bresnahan’s case, his relationship with McGraw was clearly one of the reasons. McGraw was thought of very highly in baseball circles, and his opinions drew a great deal of respect. The fact that Bresnahan was one of his favorites was certainly a contributing factor. In addition, Bresnahan passed away in December of 1944. His election in 1945 was undoubtedly aided by his passing, since many of the committee members must have voted for him out of sympathy. In the case of Schalk, his selection by the Veterans Committee in 1955 was likely his reward for not taking part in the conspiracy to throw the 1919 World Series. Whatever the reasons, the selections of both men were poor ones that did irreparable damage to the Hall of Fame by lowering the standards for future generations of players, and by lessening the integrity of the voting process.

CHANGE IN VOTING PHILOSOPHY, OR LOWERING OF THE STANDARDS?

CHANGE IN VOTING PHILOSOPHY, OR LOWERING OF THE STANDARDS?

This would probably be a good time to take a brief break from the player analysis and focus on the change in voting philosophy that has apparently transpired over the years. This change can be evidenced in two ways. First, there are the increasingly high voting percentages attained in recent years by players upon their election to the Hall of Fame. During the past two decades, a trend has developed that has enabled players whose credentials were less impressive than those of some of the great players from prior generations to garner a higher percentage of the total number of votes cast by the members of the BBWAA upon their election. In addition, once they become eligible for election, players are now being voted in far more rapidly than they were in the past.

A player who was not truly great, but merely very good, is now elected the first or second time his name appears on the ballot. Meanwhile, some of the greatest players in the history of the game previously had to wait several years before being elected. Let’s take a closer look at these trends.

When the first elections were held in 1936, with 226 members of the BBWAA casting ballots, 170 votes were needed to satisfy the minimum 75 percent requirement for election. Only Ty Cobb (222), Babe Ruth and Honus Wagner (215 each), Christy Mathewson (205), and Walter Johnson (189) received enough support from the writers to get elected. Napoleon Lajoie (146), Tris Speaker (133), Cy Young (111), and Rogers Hornsby (105) were the others who came closest to being voted in. Lajoie, Speaker, and Young were all elected the following year, and Grover Cleveland Alexander was the lone selection in 1938. In 1939, with 206 votes needed for election, George Sisler (235), Eddie Collins (213), and Willie Keeler (207) were all voted in. Hornsby, with 176 votes, once again fell short. Since no election was held in either 1940 or 1941, Hornsby had to wait until 1942 to finally be elected. Thus, one of the very greatest players in the history of the game, and the man considered by many to be the greatest righthanded hitter in baseball history, failed in his first four attempts to get elected to the Hall of Fame.

A primary source of the frustration Hornsby and several other outstanding players must have felt was unquestionably the backlog of qualified candidates that existed at that time. With the names of 15 or 20 former greats appearing on the ballot every year, the writers’ votes tended to be more scattered, and it was more difficult for any one or two players to meet the minimum 75 percent requirement. Thus, in some years, no players were selected, and some truly great ones had to wait several years before they were eventually enshrined.

However, it also appears that the writers tended to take a different attitude with them to the elections in those years, and that they viewed a player’s selection more as an

honor

than as a

right

, as they appear to do now at times. They seemed to feel that a great player eventually deserved to be voted in to the Hall of Fame, but that it would be even more of an honor if he had to wait a few years.

These days, the prevalent attitude seems to be: “Was he a very good player who probably deserves to be in Cooperstown? Yes? Okay, then let’s put him in right away.”

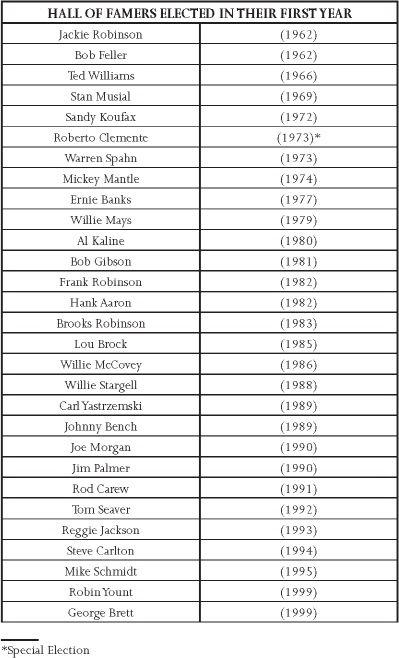

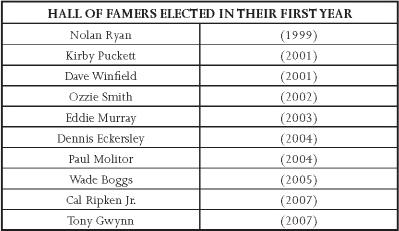

Thus, over the past two decades, some players who were clearly not among the all-time greats have been inducted into the Hall of Fame in their first year of eligibility. Following is a chart listing of all the players who have been elected to Cooperstown in the first year that their name appeared on the ballot:

This list reveals that no player was elected in his first year of eligibility prior to 1962. A look at the names on the list also reveals that all those players who were elected the first time their name appeared on the ballot during the 1960s and 1970s were among the very greatest players of all-time. However, this trend began to change somewhat during the 1980s. While Lou Brock, Willie McCovey, and Willie Stargell were all exceptional players who clearly belong in Cooperstown, could it honestly be said that they were among the all-time greats? They were certainly not on the same level as Ted Williams, Stan Musial, Mickey Mantle, and Willie Mays.

In every year from 1988 to 1995, at least one player was elected in his first year of eligibility, and, during the 1990s, the caliber of player being elected in this manner continued to decline. From Reggie Jackson (a lifetime .262 hitter) in 1993, to Robin Yount (a very good player, but certainly not a great one) in 1999, to Kirby Puckett (a borderline Hall of Famer) in 2001, the standards for first-ballot Hall of Famers have hit an all-time low.

This should not be misinterpreted to mean that these players do not belong in the Hall of Fame; they all do, with the possible exception of Puckett. But how can their first-time elections be justified when some truly great players from previous generations had to wait several years before they were finally inducted.

As an example, one needs merely to look at the elections of 1945 and 1946, when no player satisfied the minimum 75 percent requirement despite the presence on the ballot of names such as Jimmie Foxx, Lefty Grove, Charlie Gehringer, Al Simmons, Carl Hubbell, Bill Dickey, and Mickey Cochrane. Hubbell, Cochrane, and Grove were elected in 1947, along with Frankie Frisch, but Gehringer had to wait until 1949, Foxx until 1951, Simmons until 1953, and Dickey until 1954.

Even the great Joe DiMaggio, whose name appeared on the ballot for the first time in 1953, had to wait until his third year of eligibility to be voted in. In that first year, 198 votes were needed for election, but DiMaggio was named on only 117 of the ballots, thereby falling 81 votes short. Dizzy Dean and Al Simmons were elected that year. In 1954, with 189 votes needed, DiMaggio could muster only 175, thereby finishing fourth behind Rabbit Maranville, Bill Dickey, and Bill Terry, each of whom was elected that year. Finally, in 1955, when 188 votes were needed, DiMaggio was named on 223 of the ballots, thereby gaining admittance to Cooperstown.

Other outstanding players who were not elected in their first year of eligibility include:

Frankie Frisch

—elected in 1947, in his sixth time on the ballot;

Harry Heilmann

—elected in 1952, in his twelfth time on the ballot;

Bill Terry

—elected in 1954, in his fourteenth time on the ballot;

Joe Medwick

—elected in 1968, in his eighth time on the ballot;

Roy Campanella

—elected in 1969, in his fifth time on the ballot;

Yogi Berra

—elected in 1972, in his second time on the ballot;

Eddie Mathews

—elected in 1978, in his fifth time on the ballot

Some of the more notable injustices include:

Jimmie Foxx

: When Foxx’s playing career ended in 1945, it was not necessary for a player to have been retired for five seasons before he could become eligible for election. In 1946, he was named on only 26 ballots, and, in 1947, he received only 10 votes. He was finally elected in 1951, in the sixth year his name appeared on the ballot.

Lefty Grove:

In 1945, his first year of eligibility, he was named on only 28 ballots. He was elected in 1947, in his third year of eligibility.

Hank Greenberg:

In 1949, his first year of eligibility, he received only 67 votes. He was finally elected in 1956, in his eighth year of eligibility.

Carl Hubbell:

He was elected in 1947, in his fourth year of eligibility, after receiving only 24 votes in his first year.

Al Simmons:

He was elected in 1953, in his eighth year of eligibility, after receiving only one vote in his first year, and six in his second.

Charlie Gehringer:

He was elected in his fifth year of eligibility, in 1949, after receiving only ten votes in his first year.

Goose Goslin:

His name remained on the ballot from 1948 to 1962, when it was finally dropped after he received no more than 30 votes in any of his 15 years of eligibility. He was finally elected by the Veterans Committee in 1968.

Sam Crawford:

He never received more than 11 votes during his eligibility period. He was finally elected by the Veterans Committee in 1957.

Johnny Mize:

His name remained on the ballot from 1960 to 1973, until his eligibility period expired. In his first year of eligibility, he received only 45 votes. He was finally elected by the Veterans Committee in 1981.

Arky Vaughan:

He was passed on by the BBWAA from 1953 to 1968. In his first year of eligibility, he received just one vote. He was elected by the Veterans Committee in 1985.

Most of these players were as good as some of those who were later elected to the Hall of Fame in their first year of eligibility. Yet they were not ushered in with the same alacrity, in part because of the circumstances surrounding the elections in the early years, and also because of a difference in voting philosophy. This difference in philosophy can also be seen in the disparity in the voting percentages garnered by certain players at the time of their election.

For example, when Nolan Ryan was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1999, he was named on 491 of the 497 ballots cast. That comes out to 98.79 percent—the second highest percentage in the history of the voting (Tom Seaver was named on 98.8 percent of the ballots when he was elected in 1992). That means that a man who lost almost as many games as he won during his career fared better in the voting than virtually every other player who has ever lived! While Ryan was an exceptional pitcher—one who, when he was at his best, was one of the most dominant hurlers the game has seen—his career was marked with inconsistency, and it would be difficult to rank him even among the 20 greatest pitchers of all time.

Then, there is George Brett, who was also elected in 1999 when he was named on 488 of the 497 ballots cast, just three fewer than Ryan. That comes out to a percentage of 98.19, or the fourth highest ever awarded to a player. While Brett was a truly great hitter, and one of the best players of his generation, was he more deserving than Willie Mays, who, when he was elected in 1979, was named on “just” 94.7 percent of the ballots?

When Reggie Jackson was elected in 1993, he was named on 93.6 percent of the ballots. Yet, Ted Williams was named on only 93.4 percent in 1966, and Stan Musial was named on just 93.2 percent in 1969. Jackson was a great slugger, but not very many people would even mention him in the same breath with either Williams or Musial.