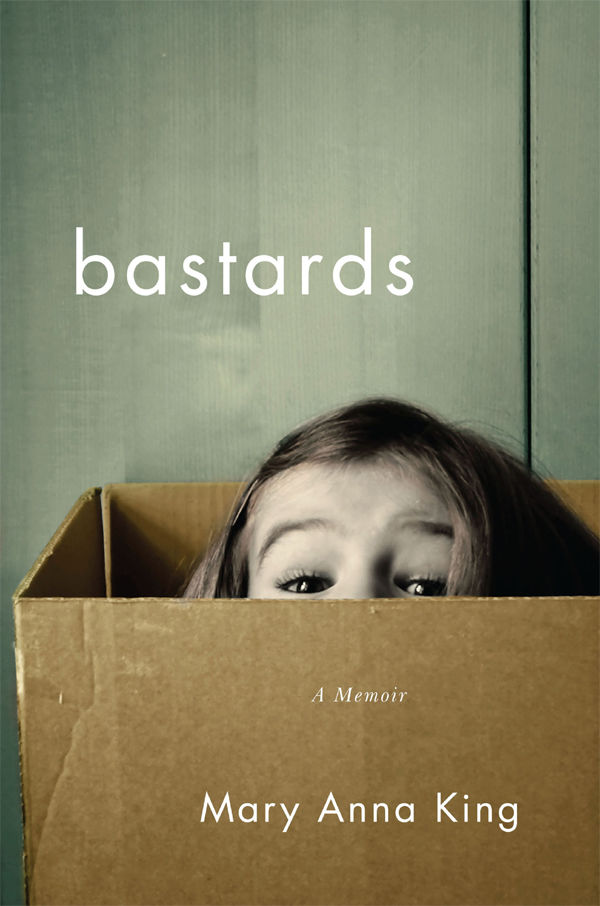

Bastards: A Memoir

Read Bastards: A Memoir Online

Authors: Mary Anna King

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Nonfiction, #Personal Memoirs, #Retail

bastards

a m e m o i r

MARY ANNA KING

For

Jacob, Becca, Lisa, Rebekah, Meghan, & Lesley

I love you, Bananas.

Contents

The Secondhand Washing Machine

Things You Can Tell Just by Looking

Note

To write this book I consulted my personal journals from my childhood. I spoke with my sisters, brother, mothers, and father, who lived through certain bits of it alongside me, though these are the events as I recall them.

When necessary, time frames have been condensed, though only when doing so would not compromise the underlying truth of the narrative. One minor character is a composite. Many names have been changed.

bastards

2009

R

emember . . . the last sense you lose is your hearing.”

My friend on the other side of the phone is a veteran intensive care nurse, so she ought to know.

“As long as she is breathing, she can hear you.”

I nod into the phone and wait for someone to helpfully shout into the receiver,

She’s nodding

, like my brother did once when we were kids. But I am standing in an airport departure gate where I am just another stranger on a cell phone, another transient whom no one will remember. My nurse friend’s voice drops into the woolly alto register of one accustomed to soothing other people.

“Don’t be surprised if it goes quickly . . . once she realizes that everyone is there.”

“Okay.”

It’s New Year’s Eve, and I’m headed to Oklahoma because my mother is dying.

I keep repeating that phrase—my mother is dying—although it isn’t quite true. I say “my mother,” because that is what people will understand.

My mother is dying

was what I said to my boss when I called him from the cab on the way to the airport, so it would be easy for him to comprehend, so the appropriate proto cols could be observed. But Mimi is not the woman who raised me all my life. She could have been, but she wasn’t. It is that arbitrariness that has led me to struggle for as long as I can remember to reconcile the person I am with the one I might have been.

As I board my plane in Los Angeles, my brother, Jacob, begins his drive to Oklahoma from south Texas, where he is stationed with the U.S. Army. When my plane lands in Dallas for a two-hour layover, he is my first phone call. On paper, Jacob is in fact my

nephew

, but to call my brother my nephew is surreal and inconceivable. “I’m a mile away, I’m coming to get you,” he says in his New Jersey drawl. In another life I had that accent, too.

I slip into the passenger seat of Jacob’s beige sedan and we drive into the worst ice storm that has hit the center of the country in one hundred years.

“Mind if I smoke?” he asks.

“Not if you give me one, too.”

He smirks and hands me the cigarette he just lit, pulling one for himself from the pack in the cup holder. We leave a trail of smoke as we drive up Interstate 35, unimpeded except for the occasional patch of black ice. Local newscasters’ crowing about the Storm of the Century has kept most other drivers off the road tonight. That and the fact that it’s New Year’s Eve. Most people in the Interstate 35 corridor from Dallas to Oklahoma City are at parties, drinking champagne and waiting for balls to drop. Mimi gave me my first sip of champagne on a New Year’s Eve seventeen years ago. I was ten years old and we were waiting to watch the fireworks over downtown Oklahoma City. She handed me a saucerlike glass with a sparkling pink liquid in it—half champagne and half strawberry Nehi soda. It was sweet and bitter and the bubbles made me sneeze.

I ask Jacob what he remembers about Oklahoma, the few years that he lived there with me, our sister Rebecca, Granddad, and Mimi. “Nothing,” he says. He clicks the radio dial to find a station that will stay free of static. We smoke two more cigarettes. We’re in the flat middle of the country. There is nothing to block the frigid wind whistling over our windshield.

When we get to Oklahoma City, we loop around the Will Rogers World Airport until Rebecca arrives from Minneapolis. It’s after ten o’clock at night by the time the three of us arrive in the intensive care unit at Baptist Hospital. Granddad is in the room with Mimi when we arrive, just as he has been since Christmas Day when she was admitted. Seventeen years ago—when Granddad became, on paper, my father—I was afraid of him, afraid of the way he could turn so quickly from the guy who sang Irving Berlin songs to wake us up in the morning to a red-faced, jaw-clenching belt-wielder. He is seventy-six now. His shoulders have rounded and he has softened.

Rebecca and I hug him and Jacob shakes his hand. “We’ll take the night shift,” I say to him. There’s a moment when all four of us look at the unconscious Mimi and listen to the sound of her breathing. It’s loud and fuzzy, an aircraft engine preparing for takeoff.

I tell Granddad what my nurse friend said on the phone, that the last sense you lose is your hearing, because I need to say something and there is nothing else to say.

He nods, and tells me he’ll be back in the morning.

Many people have an event that tears their lives into before and after. Before the divorce and after the divorce. Before the war and after the war; before 9/11 and after 9/11. If I were like most people, Mimi’s death—my mother’s death—would have been that event for me. But in fact, losing people is the only constant I know.

1983

–

1989

A

t the end of summer in 1983, I was fourteen months old, Jacob was two years, and Rebecca, whom we called Becky Jo, was two months. She was born the day after my first birthday: my only present that year. Our daddy worked construction and deejayed weddings on the weekends. Mom had been a cashier at a department store until she quit to stay home with us kids. We lived in a one-bedroom apartment in southern New Jersey, just outside of Philadelphia. My parents had been married four years. They were young. Their passions burned like an incinerator and swung wildly from love to hate and back again.

UNCLE MAC

was my daddy’s little brother, the baby of his family. He had been the best man at my parents’ wedding in 1979, and would be Becky Jo’s godfather when she was baptized. At twenty, he was a pink-cheeked homebody with a sweet singing voice and a mop of jet-black hair that waved around his cheeks and down his neck. If I dig to the deepest corners of my memory, among the pocket-lint pieces of splintered sunlight and walnut crib bars against white apartment walls, I brush against an image of my pudgy baby body lying beside my brother on deep brown shag carpet, while above us my mustachioed father and his mustachioed brother faced one another with guitars, their corded arms strumming, faces lifted like wolves howling at the moon as their voices—for moments, mere fragments of breath—met in effortless harmony. I can’t be sure if this is pure memory or something I created from stories my parents told me. My mom insists that Mac’s spirit deposited this image in my mind on one of several nights in the mid-1980s when he haunted us, his restless spirit never satisfied that we were comfortable without him.

Mac called our apartment early on Labor Day morning in 1983, before the salty south Jersey air got humid enough to suffocate a person, to invite us all to spend the day at the swimming pool where he was a lifeguard. Bringing unbaptized Becky Jo to a public pool seemed like preparing a gift too tempting for the greedy hands of fate to ignore, so Daddy told Mac that we would meet him for a cookout later that night instead.

It was late afternoon when Mac finished his shift at the pool. His friends would tell us that he was setting up the chess set in his living room, heating the grill on the balcony, and only half paying attention when his buddy Davey arrived.

Davey had just bought a gun from a guy on a gambling run at Twosies Bar across the street. It wasn’t anything fancy, a black snub-nosed .22 caliber revolver that fit in a jacket pocket, the sort of gun that wouldn’t hurt too much to lose in a round of five-card stud. Davey strolled into Mac’s apartment, put the gun to his temple, said, “Hey, look at this!” and pulled the trigger. Just joking, nothing to it, he hadn’t loaded it anyway.

If you were the kind of person who measures the success of a prank by its likelihood to cause heart attacks, this was a gold-medal winner.

The sun hadn’t yet dropped below the horizon. My mom and daddy and we three babies were stuck in a traffic jam on the White Horse Pike when the next wave of guests walked in Mac’s door. We couldn’t have been more than fifteen minutes away when Mac picked up Davey’s gun from the table, put it to his temple, and said, “Hey, look at this!”

There wasn’t any blood, the story goes. Not like you see in movies. There was only a trickle that you could make out if you got close enough to check that Mac was breathing. Everyone in the apartment thought he was horsing around. It was a really great prank, until someone realized they needed to hide the drugs and call an ambulance. There was a bullet in the chamber that sheer idiotic luck had kept from nailing Davey when he’d demonstrated the same trick.

My mom and daddy pulled into the lot of the apartment building just as the EMTs were loading Mac’s body in the ambulance. There was nothing that could be done but drive over to Grandmom Hall’s house and tell her that her baby boy was gone. Better to hear news like that from family than from a police officer. Having a grandbaby to hug can soften such a blow, too, but baby Becky Jo was a screamy thing that sucked all the available comfort out of a room, making everyone’s nerves raw and snappish. We didn’t stay long.

After that Labor Day of 1983, my daddy started disappearing. For all we knew, he was mourning in his mother’s basement, getting blasted with his construction buddies, or pawing into the ether for divine guidance to show him the way. He never packed a suitcase, never tipped his hand to us when he was planning an escape. He would go out the door one morning and not come back for days. Every time he left, it seemed like he would never return. On the nights when he did come home, he’d walk in the door, slip off his work boots, open a beer, and sit in the dark living room by himself. He’d be gone before breakfast the next morning and the cycle would start again.