Batavia (3 page)

Authors: Peter Fitzsimons

To do the story justice, thus, and put it all in context, let us begin some 135 years before its principal events occurred...

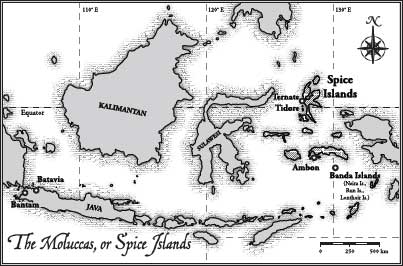

In 1492, it wasn’t just the Italian explorer Christopher Columbus who was sailing the ocean blue. Christoffa Corombo, sailing for Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella of Castile, was just one of many mariners heading out from Europe, looking for a route to the place known as the Spice Islands.

While gold may have been the common obsession of mankind since antiquity, the thing that ran it close and then surpassed it in the 1500s and 1600s was spice. Cinnamon, particularly, was so vaunted for its extraordinary medicinal powers that it was considered a cure for nothing less than the plague – ‘

No man should die

who can afford cinnamon’ was a saying of the time – and it was also regarded as an aphrodisiac, as were cloves. The reputation of cloves was particularly widespread, with the Chinese believing that, as well as being the base of perfumes, cloves mixed with milk vastly improved the pleasures of sex.

Other spices, such as nutmeg and mace – both derived from the same fruit – were valued for their medicinal qualities and as preserving agents. Most importantly, these spices, along with pepper, were prized for their extraordinary effect on the flavour of otherwise bland food. Even an amount sprinkled more sparsely than parsley could make a meal taste fit for a king, and the rich people of Europe were therefore prepared to pay a king’s ransom for it.

Pepper was so valuable it was sometimes referred to as ‘black gold’. And, while one could buy a small barrel of nutmeg weighing ten pounds in the East Indies for as little as the equivalent of a penny, in London that same amount was worth 50 shillings –

600 times its original price

.

Very few traders, other than those who conducted their business near the point of origin, actually knew where the spices came from. In order to preserve the commercial advantage of those in possession of the truth, the locations were kept a closely guarded secret – keeping the Europeans, in particular, wildly guessing.

Some said they came from tiny, exotic islands far, far to the east, protected by a monster of ‘devilish possession’ that liked nothing better than attacking passing ships. Others talked of

a faraway land peopled by warriors

whose special delight was displaying the rotting heads of their victims upon the walls of their huts. Still others believed that spices came from, or near, the Garden of Eden, which was a real place located somewhere in Asia. The point that all these stories had in common was that the spices came from a place very far away and very dangerous to reach.

The Portuguese were the first to truly locate and settle on the Spice Islands, or Moluccas. In early 1512, the Portuguese navigator António de Abreu led two ships there – specifically, to the Banda Islands – practically

smelling

their way for the last ten miles, as the delicious scent of nutmeg was carried to them across the waters. Their initial relations with the natives were friendly. For a pittance, they were able to fill their holds with both nutmeg and the cloves that came from the islands of Ternate and Tidore just over 300 miles to their north. They safely returned to Lisbon with their precious cargo, along with something equally valuable: charts directing their countrymen to the bounteous islands.

And yet, a particularly significant breakthrough followed in the early 1590s, when two Dutch brothers, by the names of Cornelis and Frederick de Houtman, were sent by a consortium of nine Dutch merchants to Lisbon to begin trading relations and find out as much about the location of the Spice Islands as they could. With precisely the latter in mind, they stole the Portuguese’s closely protected seafaring charts and were imprisoned for their trouble.

No matter. Once back in Amsterdam after three years in prison, Cornelis de Houtman managed to raise 300,000 guilders to build four ships designed specifically to get to the Spice Islands.

After engaging a crew and purchasing merchandise for trade, the de Houtmans set sail on 2 April 1595 with the

Amsterdam

,

Hollandia

,

Mauritius

and

Duyfken

– all under Cornelis’s command – for the port of Bantam, situated in the Sunda Strait, on the western tip of Java.

In many ways, it proved to be a disastrous trip, more to do with murder and pillage than with trade, but the bottom line – and that was the very line the Dutch merchants always looked to, regardless of human cost – was that when the surviving vessels got back to Amsterdam two years later, on 11 and 14 August 1597, missing two-thirds of their original crew but carrying some spice, all of Amsterdam was agog. The sale of those spices covered the 300,000 guilders invested, with a little left over.

And so it began. In March 1599, a fleet of eight ships under Jacob van Neck reached the Spice Islands. Over the next six years,

eight different companies dispatched a total of 65 ships

spread over 15 fleets, most of which returned laden with lucrative spices – although, again, there proved to be a serious commercial problem. It was one thing to have broken the Portuguese monopoly at one end, but the trade could only be truly lucrative if the Dutch merchants could establish their

own

monopoly at the other end.

There were simply too many merchants competing with each other, which drove up the price of spice in the East Indies and drove it so far down back in the Dutch Republic that it began to defeat the purpose of getting it in the first place.

Could something not be done?

To this point, Dutch merchants from six different Dutch towns had combined their resources to fund and then divide the profits from individual ventures, with this commercial union being dissolved the moment their cargo came back. But now, suddenly, a different idea, a

revolutionary

idea, took hold. Why not stay together? Why not form a ‘company’ of merchants that could establish a Dutch cartel over both the purchase and the sale of the spices? This would allow all investors in the said company to share both the risk, which would be minimised, and the profits, which would be maximised. Investors in the company could even have a certain number of ‘shares’ to register what proportion of the company they owned, shares that could rise or fall in value according to the profit being made.

Right from the beginning, those investors in the shares were drawn from all walks of Dutch life, from wealthy merchants to

labourers, housemaids and clergymen

. Their names would go into a registry and they would get receipts acknowledging how much stock they had and what they had paid for it. Now, to help those who wished to buy or sell their parts in the company, there soon developed a lively trade in those receipts, where, effectively, the stock was exchanged – so lively that a whole separate institution was soon established, called a ‘stock exchange’.

The truly revolutionary part, though, was that the members of the public who invested in the company would be able to receive regular dividends once the profits rolled in. And yet another new concept was that the company would effectively be ‘multinational’ – a business that would transcend many national borders. It would be an entirely different way of doing business.

And so, following the lead of the English, who had formed their own East India Company two years earlier – even though the English had not embraced the full corporate model – on 20 March 1602 the Dutch formed the Dutch East India Company (

Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie

, or VOC), with the full force of the Dutch Government behind it.

The VOC was granted by its government not only the sole right to Asian trade but also the right to engage in areas of activity usually reserved for the state: establishing colonies, coining monies, maintaining private armies and navies, fighting the enemies of the Republic, signing treaties with Asian potentates, building forts in the islands they were trading with and even subjugating entire populations. Not for nothing was it known as a state within a state. In fact, it was one destined to soon be more powerful than the state that had fathered it, as it had the entire world in which to expand.

The leadership of the VOC, known as the

Heeren XVII

, the Lords XVII, directed everything from the shipbuilding activities in their six trading towns (Amsterdam, Middelburg, Hoorn, Deft, Rotterdam and Enkhuizen) to determining precisely where those ships would sail, who would man them and who they would trade with. Each ship proudly flew the company’s own flag from her stern, with the initial of the originating town worked into the company’s logo – the first logo of the first public company. Henceforth in Dutch national life, any reference to ‘the Company’, of course with a capital ‘C’, was ever and always a reference to the single most important institution in the country, the VOC.

With such extraordinary profits on offer, wasted time was wasted money – and, as a secondary consideration, wasted lives. Many men could be expected to die in a gruelling year-long journey to the East Indies, and the majority of those deaths typically came in the last months. If a quicker way to travel could be found, there would be far less bother about always having to find new employees to replace the perished ones.

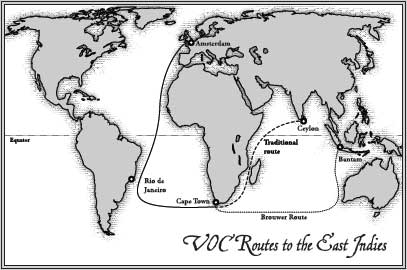

A notable breakthrough came in 1611 when a brave captain with the VOC, Hendrick Brouwer, decided to try something new. Up until then, having passed the tip of South Africa heading east, one tightly adhered to the sight of land then bobbled roughly north-eastwards up along the east African coast, via Mombasa, meandered across the Arabian Sea to India, then on to Ceylon, before at last heading over to the East Indies via the Strait of Malacca.

Brouwer had no patience for this ‘slow boat to China’ method, which required around 12 months’ sailing to get from Amsterdam to the East Indies, and wondered what winds might be out in the open ocean that – despite the risk of being well away from land – would make the trip quicker. Thus, having rounded the Cape of Good Hope, instead of navigating nor’ by nor’-east to keep the east coast of Africa off his port quarter, he headed east and . . .

And he was soon near blown away by what he discovered. Once he was out into that open ocean, there proved to be a consistent enormous wind blowing from right behind him, a wind they called

Westenwindengordel

, west-wind-belt. Captain Brouwer and his crew were soon hurtling eastwards at a speed never before imagined possible. The

Westenwindengordel

, it was found, was at its strongest and most constant in the latitudes between 40 and 50 degrees south – a region that would become known as the Roaring Forties.

Brouwer’s plan at this point was to keep close estimation of the distance travelled each day so he would be able to work out when he was due south of the East Indies, on a longitude some 4000 miles east of the Cape, at which point he intended to turn north towards the Sunda Strait.

It all worked perfectly. Brouwer made his calculations, turned to the north at the right time and his ship arrived in Bantam a staggering six months earlier than predicted – what’s more, with a crew that was much healthier than normal. A new era in international maritime trade had begun.

It was not always so easy, however, to calculate the right time for turning north, as a Dutch captain by the name of Dirk Hartog discovered while testing it in 1616. He left Texel – the island north-west of Amsterdam used as a roadstead for a lot of Dutch shipping – on 23 January in his ship the

Eendracht

on her maiden voyage, carrying ten money chests loaded with 80,000 reals, the silver Spanish coins also known as pieces of eight. They reached the Cape of Good Hope on 5 August and stayed there for just over three weeks, before heading out on Brouwer’s route.

Now, likely because of the vagaries of the currents, Hartog turned his ship north at a later point than Brouwer had, and, while crossing the line of roughly 26 degrees south on 25 October 1616, he suddenly came upon

‘various islands, which were, however, found uninhabited’

. After dropping anchor, Hartog was rowed ashore and briefly explored the main island, staying there for three days and naming it Eendrachtsland, after his ship.