Batavia (6 page)

Authors: Peter Fitzsimons

No matter that Jacobsz was a superb mariner, the truth of it was that, within the confines of a VOC ship, Pelsaert had nearly all the power and Jacobsz next to none, apart from that which directly concerned the sailing of the ship. A lesser man than Jacobsz might have swallowed his contempt for Pelsaert and everything he stood for, but Jacobsz, a skipper given to choleric outbursts of anger, could not. In fact, his first verbally violent confrontation with Pelsaert came so early in the voyage that . . . well . . . the

Dordrecht

was still berthed in the harbour at the time, getting ready to sail.

Pelsaert was not the only one scandalised by Jacobsz’s insolence. It is recorded that immediately after the confrontation, two senior VOC officers also on board addressed Jacobsz in the strongest possible terms and informed him that this was ‘

not the manner in which to sail

to the Fatherland. Jacobsz must behave himself differently toward Pelsaert.’ Seething, Jacobsz just managed to control himself, grumbled a rough apology and kept his distance from the infernally prissy and officious Pelsaert for the rest of the journey.

In the Dutch Republic, meanwhile, a man by the name of Jeronimus Cornelisz was becoming very nervous. Hailing from the northern province of Friesland, Jeronimus was a tall, exceptionally lean man with a delicate, almost feminine, face of the finely drawn variety, and the lazy, hooded eyes of a cobra. A refined, silken, louche man, he boasted long ringlets of hair that cascaded softly over his narrow shoulders and, strangely, always seemed to have the barest hint of perfume about him. Jeronimus was a dandy with a death’s head smile, a man with a malevolent and Machiavellian charisma, softly spoken and persuasive, yet entirely without conscience. In his late 20s, he had become a member of the intimate circle of the notorious artist Torrentius, whose name had become a byword for evil.

There was no doubt about Torrentius’s skill as a painter, as he was highly regarded for his still lifes and portraiture. That was not the issue. Nor was it just that Torrentius was a blasphemer. It was the terrible things that his lack of respect for the Lord made him do. In his life of drunken dissolution, he frequently and publicly expressed heretical views that there were no such things as heaven and hell. What is more, he claimed that since they didn’t exist, there was no risk in doing nominally bad things on earth. And besides, because God was omnipresent, and God was in us all, there was nothing one could do that wasn’t God’s will in the first place. Therefore, one was entirely free to do whatever one wanted, such as solely devoting oneself to the pursuit of pleasure, and Torrentius was certainly one to practise what he preached.

Perhaps worst of all in the eyes of the authorities, though, Torrentius was rumoured to be a member of the secret and sacrilegious Rosicrucian order, established some 200 years earlier by the German mystic Christian Rosenkreuz. Of course, any secret organisation composed of people of power and influence that was not only advocating the transformation of the entire social, intellectual, political and religious systems but also seeking adherents with equally heretical views was a threat to the Dutch state. It would, therefore, have to be dealt with by that state, using whatever means necessary.

In mid-1627, the authorities inevitably came for Torrentius. In early 1628, after months of torture and interrogation, he was sentenced to 22 years’ imprisonment. Now the authorities were hunting down all of his known associates.

As documented in Mike Dash’s book,

Batavia’s Graveyard

, Jeronimus was a man with many other pressing problems, independent of his link with Torrentius. In recent times, his business in Haarlem as an apothecary– a purveyor of potions, powders, poultices, plant life and products deriving from animals – had teetered on bankruptcy. He and his wife had recently lost an infant child to syphilis, though whether that was contracted from Jeronimus’s wife, as many claimed, or from the wet nurse, as the devastated couple insisted, was

a moot point

. Either way, there were too many people who believed the ‘Neapolitan scab’, as it was known, originated with the couple and therefore did not wish to purchase their pills and potions from one so disease-ridden. Consequently, the apothecary business of Jeronimus was soon decimated. Between his shattered reputation, penury and the authorities closing in because of his Rosicrucianism, Jeronimus came to the conclusion that

Haarlem was no place for him to be

.

With that, in early October 1628, he left the northern city without his wife to go to Amsterdam in the east, to look for an opportunity to start over. Yes, Amsterdam, Europe’s great city of trade, was the place for Jeronimus to lose himself and then find himself again, to seek out an opportunity to completely change his life. Well educated by the standards of the day, he was not without his prospects for gainful employment. However, with no money, no backing, few friends and no certainty that the authorities would not soon pursue him there, he was never going to find it easy.

With time of the essence, Jeronimus pressed on, looking for employment in any maritime venture that would take him far from the strictures of the Dutch Republic and perhaps allow him to start afresh in a new world, where there might be no strictures at all . . .

His timing was good. For, just a month before Jeronimus arrived in Amsterdam, the outgoing Governor-General of Batavia in the Dutch East Indies, General Pieter Carpentier, whom Coen had replaced, returned to the Dutch capital in triumph. Now the VOC’s commercial chief of the entire VOC fleet, in charge of overseeing and controlling all new trading opportunities and financial operations, Carpentier personally commanded the successful return to Amsterdam of five VOC ships, heavily laden with spices and worth a fortune to the Company. Clearly, the conditions were right at that time for importing ever more spices from the East Indies, and the mighty

Heeren XVII

moved quickly to send as many ships as possible to Batavia, which would, God willing, quickly return fully laden with the precious, lucrative cargo.

There proved to be 11 such ships available to leave at relatively short notice, the pride of which was the mighty

Batavia

. She hadn’t been built so much as crafted over the previous year and was just being made ready to launch on this, her maiden voyage. Constructed in the Amsterdam shipyards – the

Peperwerf

on the small island of Rapenburg – the

Batavia

was a classic

retourschip

, return ship, designed specifically for the journey to the East Indies and back. At 165 feet long and an even more impressive 40 feet wide in the beam and 16 and a half feet deep at the keel, this

retourschip

was three times the size of the

Santa María

, the ship in which Christopher Columbus had sailed in 1492.

The

Batavia

had three enormous masts of Scandinavian pine capable of holding ten sails with just under 9000 square feet of canvas to the wind. At a cost of 100,000 guilders, she was built by none other than the pre-eminent shipbuilder of the day, Jan Rijksen, who closely supervised the whole construction process. The heavy timber frame was composed of massive pieces of oak, specially selected because their natural shape suited the design. Each piece was soaked in seawater for a full six months before being further coaxed into precisely the desired camber, with planks of the finest Danish oak forming the shell of the round-bellied hull. For protection against shipworm – known as the ‘termites of the sea’ for their propensity for boring into all wood immersed in the ocean – Rijksen put a layer of tar mixed with horsehair on the outside of the hull and sheathed the whole thing with a thin layer of pine studded with thick iron nails, upon which no shipworm would make any headway, at least not for some time. Those nails had large square heads, hammered so close to each other that they formed another impenetrable layer of rusty iron. Still not done in providing protection, Rijksen saw that the whole outside layer was laboriously painted with a ghoulish mix designed to forestall any shipworm even beginning to bore – a concoction of lime, oil, resin and sulphur. If this ship ever sank, it would not be because of shipworm.

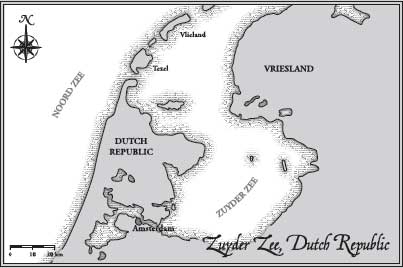

After five or so months, once that shell was completed, it was floated some 50 yards out in the

Zuyder Zee

, Southern Sea, a shallow bay of the North Sea that extends some 60 miles into the heart of the Netherlands. Here, the ship was ‘caged’ in a wooden enclosure of palisades set firmly into the river bottom. This meant that the

Peperwerf

could be freed up to build the next ship, while workers could continue within that shell, adding the three basic decks lying at the

Batavia

’s core.

In total, there was no fewer than 60,000 cubic feet of oak used in her construction, giving her an unladen weight of 600 tons, even before her 30 shining cannons were rolled on board and myriad supplies laboriously loaded in the hold. All of the cannons near the helm of the ship, where all of the navigation would take place, were made of bronze rather than iron, so they would not affect the readings of the instrument upon which the lives of her crew depended: the magnetic compass. All the implements used to ram the gunpowder into the normal iron cannons, meanwhile, were made of brass – to avoid any chance of a spark lighting the gunpowder before the cannonball was loaded and ready to fire.

Because of the need for speed to get the

Batavia

on her way, the Company urgently sought to fill the roster with VOC commercial officers and an expert sailing crew, not to mention carpenters, cooks, tailors and all the rest to keep the ship smoothly functioning. Also, the Company would need enough mercenary soldiers signed to five-year contracts on-board, firstly to ensure the security of the ship against internal and external attacks – the Dutch at this point were at war with both Portugal and Spain – and secondly, upon arrival in Batavia, to fill the garrison to compensate for its dreadful rates of attrition. There was, thus, a highly disparate set of skills required at short notice to man the large fleet.

As luck would have it, the desperation of the VOC to quickly fill that roster – and not be too particular about whom they took – was precisely matched by the desperation of those applying to fill the positions. The trip to the East Indies was long, fraught and poorly paid – particularly when compared with the staggering profits that the Company could make out of it. Should one actually survive the journey, then the chances of remaining alive for any period of time in the East Indies – against the many threats of malaria, dysentery, smallpox, cholera, typhoid, leprosy, yellow fever and other miscellaneous tropical diseases and ailments, not to mention the native attacks that constantly beset Batavia’s population – were as skinny as an Amsterdam street urchin.

Hence, the link between applicants turning up to the VOC’s East India House – the imposing building that stood on the corner of Amsterdam’s

Hoogstraat

and

Kloveniersburgwal

– and even those paying passengers who sought a berth to the East Indies was an obvious one: desperation. They could be desperately poor, desperate to escape the Dutch Republic for whatever reason, desperate to join a loved one in Batavia, or just generally

a

desperate.

Jeronimus Cornelisz, who could fairly be described as fulfilling three of those four categories, decided to apply. He was in the company of ‘all sorts of krauts, bumpkins, clodhoppers, haymakers and

other raw kashoobs

with grass still stuck between their teeth’. They were an odd collection of men, looking to make a very long journey.

CHAPTER ONE

Across the Seven Seas

Zo wijd de wereld strekt. . .

(As far as the world extends . . .)

The Royal Dutch Marines’ motto

27 October 1628, Amsterdam

It is a strange thing to finally live out, moment by moment, the realisation of a lifelong dream – to compare what is happening on the instant to how you repeatedly imagined it would be.

As the strengthening breeze on the

Zuyder Zee

pushes back the single wisp of blonde hair that has just escaped from beneath Lucretia Jans’s stylish blue bonnet, the lady carefully tucks it back in. And then she leans out over the bow of the

kaag

, the small sailing vessel that is bearing her towards the spot where the

mighty East Indiaman

Batavia

awaits her, and continues waving at the tiny stick figures back on the shore. They are her two sisters and her most intimate circle of friends, who, even now, are beginning to blend into the amorphous mass of well-wishers gathered around Amsterdam’s Montelbaans Tower.

Lucretia now stands still in the early morning light, before she comes back from the railing and takes stock. Because of Amsterdam’s shallow harbour, it is necessary for all ships of the

Batavia

’s grandeur and deep draught to go to Texel, at the far end of the

Zuyder Zee

, near the entrance to the North Sea. All passengers and supplies can be brought to the large ships berthed here in smaller vessels to load them up over a period of weeks before they set sail.