Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (146 page)

Read Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era Online

Authors: James M. McPherson

Tags: #General, #History, #United States, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #United States - History - Civil War; 1861-1865, #United States - History - Civil War; 1861-1865 - Campaigns

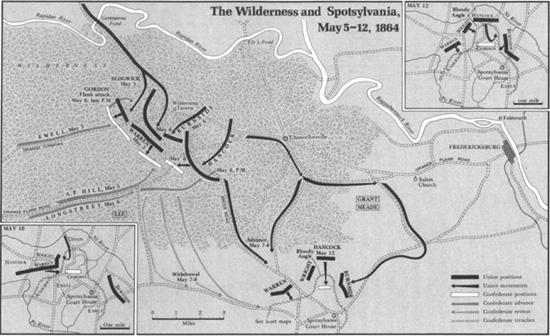

The failure of Grant's leg-holders in Virginia complicated the task of skinning Lee. The Armies of the Potomac and of Northern Virginia had wintered a few miles apart on opposite sides of the Rapidan. As the dogwood bloomed, Grant prepared to cross the river and turn Lee's right. He hoped to bring the rebels out of their trenches for a showdown battle somewhere south of the Wilderness, that gloomy expanse of scrub oaks and pines where Lee had mousetrapped Joe Hooker exactly a year earlier. Remembering that occasion, Lee decided not to contest the river crossing but instead to hit the bluecoats in the flank as they marched through the Wilderness, where their superiority in numbers—115,000 to 64,000—would count for less than in the open.

12

.

O.R.

, Ser. I, Vol. 46, pt. 1, p. 20.

13

.

Ibid

., Vol. 36, pt. 2, p. 840.

Accordingly on May 5 two of Lee's corps coming from the west ran into three Union corps moving south from the Rapidan. For Lee this collision proved a bit premature, for Longstreet's corps had only recently returned from Tennessee and could not come up in time for this first day of the battle of the Wilderness. The Federals thus managed to get more than 70,000 men into action against fewer than 40,000 rebels. But the southerners knew the terrain and the Yankees' preponderance of troops produced only immobility in these dense, smoke-filled woods where soldiers could rarely see the enemy, units blundered the wrong way in the directionless jungle, friendly troops fired on each other by mistake, gaps in the opposing line went unexploited because unseen, while muzzle flashes and exploding shells set the underbrush on fire to threaten wounded men with a fiery death. Savage fighting surged back and forth near two road intersections that the bluecoats needed to hold in order to continue their passage southward. They held on and by dusk had gained a position to attack Lee's right.

Grant ordered this done at dawn next day. Lee likewise planned a dawn assault in the same sector to be spearheaded by Longstreet's corps, which was on the march and expected to arrive before light. The Yankees attacked first and nearly achieved a spectacular success. After driving the rebels almost a mile through the woods they emerged into a small clearing where Lee had his field headquarters. Agitated, the gray commander tried personally to lead a counterattack at the head of one of Longstreet's arriving units, a Texas brigade. "Go back, General Lee, go back!" shouted the Texans as they swept forward. Lee finally did fall back as more of Longstreet's troops double-timed into the clearing and brought the Union advance to a halt.

The initiative now shifted to the Confederates. By mid-morning Longstreet's fresh brigades drove the bluecoats in confusion almost back to their starting point. The southerners' local knowledge now came into play. Unmarked on any map, the roadbed of an unfinished railroad ran past the Union left. Vines and underbrush had so choked the cut that an unwary observer saw nothing until he stumbled into it. One of Longstreet's brigadiers knew of this roadbed and suggested using it as a concealed route for an attack against the Union flank. Longstreet sent four brigades on this mission. Shortly before noon they burst out of thickets and rolled up the surprised northern regiments. Then tragedy struck the Confederates as it had done a year earlier only three miles away in this same Wilderness. As the whooping rebels drove in from the flank they converged at right angles with Longstreet's other units attacking straight ahead. In the smoke-filled woods Longstreet went down with a bullet in his shoulder fired by a Confederate. Unlike Jackson he recovered, but he was out of the war for five months.

With Longstreet's wounding the steam went out of this southern assault. Lee straightened out the lines and renewed the attack in late afternoon. Combat raged near the road intersection amid a forest fire that ignited Union breastworks. The Federals held their ground and the fighting gradually died toward evening as survivors sought to rescue the wounded from cremation. At the other end of the line General John B. Gordon, a rising brigadier from Georgia, discovered that Grant's right flank was also exposed. After trying for hours to get his corps commander Richard Ewell to authorize an attack, Gordon went to the top and finally obtained Lee's permission to pitch in. The evening assault achieved initial success and drove the Federal flank back a mile while capturing two northern generals. Panic spread all the way to Grant's headquarters, where a distraught brigadier galloped up on a lathered horse to tell the Union commander that all was lost—that Lee was repeating Jackson's tactics of a year earlier in these same woods. But Grant did not share the belief in Lee's superhuman qualities that seemed to paralyze so many eastern officers. "I am heartily tired of hearing what Lee is going to do," Grant told the brigadier. "Some of you always seem to think he is suddenly going to turn a double somersault, and land on our rear and on both our flanks at the same time. Go back to your command, and try to think what we are going to do ourselves, instead of what Lee is going to do."

14

Grant soon showed that he meant what he said. Both flanks had been badly bruised, and his 17,500 casualties in two days exceeded the Confederate total by at least 7,000. Under such circumstances previous Union commanders in Virginia had withdrawn behind the nearest river. Men in the ranks expected the same thing to happen again. But Grant had told Lincoln that "whatever happens, there will be no turning back."

15

While the armies skirmished warily on May 7, Grant prepared to march around Lee's right during the night to seize the crossroads village of Spotsylvania a dozen miles to the south. If successful, this move would place the Union army closer to Richmond than the enemy and force Lee to fight or retreat. All day Union supply wagons and the reserve artillery moved to the rear, confirming the soldiers' weary expectation of retreat. After dark the blue divisions pulled out one by one. But

14

. Horace Porter,

Campaigning with Grant

(New York, 1897), 69–70.

15

. Foote,

Civil War

, III, 186.

instead of heading north they turned

south

. A mental sunburst brightened their minds. It was not "another Chancellorsville . . . another skedaddle" after all. "Our spirits rose," recalled one veteran who remembered this moment as a turning point in the war. Despite the terrors of the past three days and those to come, "we marched free. The men began to sing." For the first time in a Virginia campaign the Army of the Potomac stayed on the offensive after its initial battle.

16

Sheridan's cavalry had thus far contributed little to the campaign. Their bandy-legged leader was eager to take on Jeb Stuart's fabled troopers. Grant obliged Sheridan by sending him on a raid to cut Lee's communications in the rear while Grant tried to pry him out of his defenses in front. Aggressive as always, Sheridan took 10,000 horsemen at a deliberate pace southward with no attempt at deception, challenging Stuart to attack. The plumed cavalier chased the Yankees with only half his men (leaving the others to patrol Lee's flanks at Spotsylvania), nipping at Sheridan's heels but failing to prevent the destruction of twenty miles of railroad, a quantity of rolling stock, and three weeks' supply of rations for Lee's army. On May 11, Stuart made a stand at Yellow Tavern, only six miles north of Richmond. Outnumbering the rebels by two to one and outgunning them with rapid-fire carbines, the blue troopers rolled over the once-invincible southern cavalry and dispersed them in two directions. A grim bonus of this Union victory was the mortal wounding of Stuart—a blow to Confederate leadership next only to the death of Jackson a year and a day earlier.

While the cavalry played its deadly game of cut and thrust near Richmond, the infantry back at Spotsylvania grappled like muscle-bound giants. By this stage of the war the spade had become almost as important for defense as the rifle. Wherever they stopped, soldiers quickly constructed elaborate networks of trenches, breastworks, artillery emplacements, traverses, a second line in the rear, and a cleared field of fire in front with the branches of felled trees (abatis) placed at point-blank range to entangle attackers. At Spotsylvania the rebels built the strongest such fieldworks in the war so far. Grant's two options were to flank these defenses or smash through them; he tried both. On May 9 he sent Winfield Scott Hancock's 2nd Corps to turn the Confederate left. But this maneuver required the crossing of a meandering river twice, giving Lee time to shift two divisions on May 10 to counter it. Believing that this weakening of the Confederate line made it vulnerable to assault,

16

.

Ibid.

, 189–91; Catton, A

Stillness at Appomattox

, 91–92.

Grant ordered five divisions to attack the enemy's left-center on a mile-wide front during the afternoon of May 10. But they found no weakness, for Lee had shifted those reinforcements from his right.

Farther along toward the center of the line, however, on the west face of a salient jutting out a half-mile along high ground and dubbed the Mule Shoe because of its shape, a Union assault achieved a potentially decisive breakthrough. Here Colonel Emory Upton, a young and intensely professional West Pointer who rarely restrained his impatience with the incompetence he found among fellow officers, made a practical demonstration of his theory on how to attack trenches. With twelve picked regiments formed in four lines, Upton took them across 200 yards of open ground and through the abatis at a run. Not stopping to fire until they reached the trenches, screaming like madmen and fighting like wild animals, the first line breached the defenses and fanned left and right to widen the breach while the following line kept going to attack the second network of trenches a hundred yards farther on. The third and fourth lines came on and rounded up a thousand dazed prisoners. The road to Richmond never seemed more open. But the division assigned to support Upton's penetration came forward halfheartedly and retreated wholeheartedly when it ran into massed artillery fire. Stranded without support a half-mile from their own lines, Upton's regiments could not withstand a withering counterattack by rebel reinforcements. The Yankees fell back in the gathering darkness after losing a quarter of their numbers.

Their temporary success, however, won Upton a battlefield promotion and persuaded Grant to try the same tactics with a whole corps backed by follow-up attacks all along the line. As a cold, sullen rain set in next day (May 11) to end two weeks of hot weather, reports by rebel patrols of Union supply wagons moving to the rear caused Lee to make a wrong guess about Grant's intentions. Believing that the wagon traffic presaged another flanking maneuver, Lee ordered the removal of twenty-two guns in preparation for a quick countermove. The apex of the salient defended by these guns was exactly the point that Hancock's corps planned to hit at dawn on May 12. Too late the guns were ordered back—just in time to be captured by yelling bluecoats as fifteen thousand of them swarmed out of the mist and burst through the Confederate trenches. Advancing another half-mile and capturing most of the famed Stonewall division, Hancock's corps split Lee's army in two. At this crisis the southern commander came forward with a reserve division. As he had done six days previously in the Wilderness, Lee started to lead them himself in a desperate counterattack. Again the soldiers—Virginians and Georgians this time—shouted "General Lee to the rear!" and vowed to drive back "those people" if Marse Robert would only stay safely behind. Lee acceded, and the division swept forward. Their counterattack benefited from the very success of the Yankees, whose rapid advance in rain and fog had jumbled units together in a disorganized mass beyond control of their officers. Forced back to the toe of the Mule Shoe, bluecoats rallied in the trenches they had originally captured and there turned to lock horns with the enemy in endless hours of combat across a no-man's land at some places but a few yards wide.

While this was going on the Union 5th and 9th Corps attacked the left and right of the Confederate line with little success, while the 6th Corps came in on Hancock's right to add weight to a renewed attempt to crush the salient. Here was the famous Bloody Angle of Spotsylvania. For eighteen hours in the rain, from early morning to midnight, some of the war's most horrific fighting raged along a few hundred yards of rebel trenches. "The flags of both armies waved at the same moment over the same breastworks," recalled a 6th Corps veteran, "while beneath them Federal and Confederate endeavored to drive home the bayonet through the interstices of the logs."

17

Impelled by a sort of frenzy, soldiers on both sides leaped on the parapet and fired down at enemy troops with bayoneted rifles handed up from comrades, hurling each empty gun like a spear before firing the next one until shot down or bayoneted themselves. So intense was the firing that at one point just behind the southern lines an oak tree nearly two feet thick was cut down by minié balls.

18