Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (149 page)

Read Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era Online

Authors: James M. McPherson

Tags: #General, #History, #United States, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #United States - History - Civil War; 1861-1865, #United States - History - Civil War; 1861-1865 - Campaigns

Thus ended a seven-week campaign of movement and battle whose brutal intensity was unmatched in the war. Little wonder that the Army of the Potomac did not fight at Petersburg with "the vigor and force" it had shown in the Wilderness—it was no longer the same army. Many of its best and bravest had been killed or wounded; thousands of others,

34

. Catton, A

Stillness at Appomattox

, 196.

35

.

O.R.

, Ser. I, Vol. 40, pt. 2, pp. 179, 205.

36

. Catton, A

Stillness at Appomattox

, 198, 199;

O.R

., Ser. I, Vol. 40, pt. 2, pp. 156–57.

their enlistments expired or about to expire, had left the war or were unwilling to risk their lives during the few days before leaving. Some 65,000 northern boys were killed, wounded, or missing since May 4. This figure amounted to three-fifths of the total number of combat casualties suffered by the Army of the Potomac during the

previous three years

. No army could take such punishment and retain its fighting edge. "For thirty days it has been one funeral procession past me," cried General Gouverneur K. Warren, commanding the 5th Corps, "and it has been too much!"

37

Could the northern people absorb such losses and continue to support the war? Financial markets were pessimistic; gold shot up to the ruinous height of 230. A Union general home on sick leave found "great discouragement over the North, great reluctance to recruiting, strong disposition for peace."

38

Democrats began denouncing Grant as a "butcher," a "bull-headed Suvarov" who was sacrificing the flower of American manhood to the malign god of abolition. "Patriotism is played out," proclaimed a Democratic newspaper. "Each hour is but sinking us deeper into bankruptcy and desolation." Even Benjamin Butler's wife wondered "what is all this struggling and fighting for? This ruin and death to thousands of families? . . . What advancement of mankind to compensate for the present horrible calamities?"

39

Lincoln tried to answer such anguished queries in a speech to a fund-raising fair of the Sanitary Commission in Philadelphia on June 16. He conceded that this "terrible war" had "carried mourning to almost every home, until it can almost be said that 'the heavens are hung in black.' " To the universal question, "when is the war to end?" Lincoln replied: "We accepted this war for [the] worthy object . . . of restoring the national authority over the whole national domain . . . and the war will end when that object is attained. Under God, I hope it never will until that time. [Great Cheering] . . . General Grant is reported to have said, I am going through on this line if it takes all summer. [Cheers] . . . I say we are going through on this line if it takes three years more.

37

. George R. Agassiz, ed.,

Meade's Headquarters

, 1863–1865;

Letters of Colonel Theodore Lyman

(Boston, 1922), 147.

38

. John H. Martindale to Benjamin Butler, Aug. 5, 1864, in Jesse A. Marshall, ed.,

Private and Official Correspondence of General Benjamin F. Butler during the Period of the Civil War

, 5 vols. (Norwood, Mass., 1917), V, 5.

39

. Frank L. Klement,

The Copperheads in the Middle West

(Chicago, 1960), 233; Mrs. Sarah Butler to Benjamin Butler, June 19, 1864, in Marshall, ed.,

Correspondence of Benjamin Butler

, IV, 418.

[Cheers]" This Spartan call for a fight to the finish must have offered cold comfort to many listeners, despite the cheers.

40

In his speech Lincoln praised Grant for having gained "a position from whence he will never be dislodged until Richmond is taken." And indeed, despite its horrendous losses the Army of the Potomac had inflicted a similar percentage of casualties (at least 35,000) on Lee's smaller army, had driven them south eighty miles, cut part of Lee's communications with the rest of the South, pinned him down in defense of Richmond and Petersburg, and smothered the famed mobility of the Army of Northern Virginia. Lee recognized the importance of these enemy achievements. At the end of May he had told Jubal Early: "We must destroy this army of Grant's before it gets to the James River. If he gets there it will become a siege, and then it will be a mere question of time."

41

II

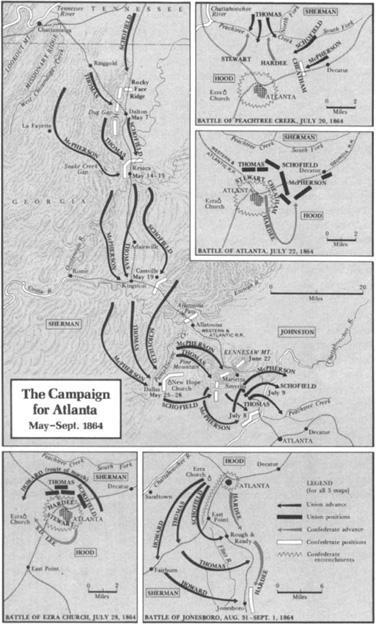

In the long run, to be sure, Lee and the South could not withstand a siege. But in the short run—three or four months—time was on the Confederacy's side, for the northern presidential election was approaching. In Georgia as well as Virginia the rebels were holding out for time. At the end of June, Joe Johnston and Atlanta still stood against Sherman despite an eighty-mile penetration by the Yankees in Georgia to match their advance in Virginia.

While Grant and Lee sought to destroy or cripple each other's army, Sherman and Johnston engaged in a war of maneuver seeking an advantage that neither found. While Grant continually moved around Lee's right after hard fighting, Sherman continually moved around Johnston's left without as much fighting. Differences in terrain as well as in the personalities of commanders determined these contrasting strategies. Unlike Lee, whom necessity compelled to adopt a defensive strategy, Johnston by temperament preferred the defensive. He seemed to share with his prewar friend George McClellan a reluctance to commit troops to all-out combat; perhaps for that reason Johnston was idolized by his men as McClellan had been. In Virginia in 1862, Johnston had retreated from Manassas without a battle and from Yorktown almost to Richmond with little fighting. In Mississippi he never did come to grips

40

.

CWL

, VII, 394–95

41

.

Ibid.

, 396; Foote,

Civil War

, III, 442.

with Grant at Vicksburg. This unwillingness to fight until everything was just right may have been rooted in Johnston's character. A wartime story made the rounds about an antebellum visit by Johnston to a plantation for duck hunting. Though he had a reputation as a crack shot, he never pulled the trigger. "The bird flew too high or too low—the dogs were too far or too near—things never did suit exactly. He was . . . afraid to miss and risk his fine reputation."

42

In the spring of 1864 Jefferson Davis prodded Johnston to make some move against Sherman before Sherman attacked him. But Johnston preferred to wait in his prepared defenses until Sherman came so close that he could not miss.

Sherman refused to oblige him. Despite his ferocious reputation, "Uncle Billy" (as his men called him) had little taste for slam-bang combat: "Its glory is all moonshine; even success the most brilliant is over dead and mangled bodies, with the anguish and lamentation of distant families."

43

Sherman's invasion force consisted of three "armies" under his single overall command: George Thomas's Army of the Cumberland, now 60,000 strong including the old 11th and 12th Corps of the Army of the Potomac reorganized as the 20th Corps; 25,000 men in the Army of the Tennessee, which had been Grant's first army and then Sherman's and was now commanded by their young protégé James B. McPherson; and John M. Schofield's 13,000-man corps, called the Army of the Ohio, which had participated in the liberation of east Tennessee the previous autumn. This composite army was tied to a vulnerable single-track railroad for its supplies. The topography of northern Georgia favored the defense even more than in Virginia. Steep, rugged mountains interlaced by swift rivers dominated the landscape between Chattanooga and Atlanta. Johnston's army of 50,000 (soon to be reinforced to 65,000 by troops from Alabama) took position on Rocky Face Ridge flanking the railroad twenty-five miles south of Chattanooga and dared the Yankees to come on.

Sherman declined to enter this "terrible door of death." Instead, like a boxer he jabbed with his left—Thomas and Schofield—to fix Johnston's attention on the ridge, and sent McPherson on a wide swing to the right through mountain gaps to hit the railroad at Resaca, fifteen miles in the Confederate rear. Through an oversight by Johnston's cavalry, Snake Creek Gap was almost unguarded when McPherson's fast-marching infantry poured through on May 9. Finding Resaca protected

42

. Woodward,

Chesnut's Civil War

, 268.

43

. Basil H. Liddell Hart,

Sherman: Soldier, Realist, American

(New York, 1929), 402.

by strong earthworks, however, McPherson skirmished cautiously, overestimated the force opposing him (there were only two brigades), and pulled back without reaching the railroad. Alerted to this threat in his rear, Johnston sent additional troops to Resaca and then retreated with his whole army to this point on the night of May 12–13. Sherman's knockout punch never landed. "Well, Mac," he told the chagrined McPherson, "you missed the opportunity of your life."

44

For three days Sherman's whole force probed the Resaca defenses without finding a weak spot. Once again part of McPherson's army swung southward by the right flank, crossed the Oostanaula River, and threatened Johnston's railroad lifeline. Disengaging skillfully, the southerners withdrew down the tracks, paused briefly fifteen miles to the south for an aborted counterpunch against the pursuing Yankees, then continued another ten miles to Cassville, where they turned at bay. The rebels wrecked the railroad as they retreated, but Uncle Billy's repair crews had it running again in hours and his troops remained well supplied. In twelve days of marching and fighting, Sherman had advanced halfway to Atlanta at a cost of only four or five thousand casualties on each side. The southern government and press grew restive at Johnston's retreats without fighting. So did some soldiers. "The truth is," wrote a private in the 29th Georgia to his wife, "we have run until I am getting out of heart & we must make a Stand soon or the army will be demoralized, but all is in good spirits now & beleave Gen. Johnston will make a stand & whip the yankees badley."

45

Johnston's most impatient subordinate was John Bell Hood. The crippling of Hood's left arm at Gettysburg and the loss of his right leg at Chickamauga had done nothing to abate his aggressiveness. Schooled in offensive tactics under Lee, Hood had remained with the Army of Tennessee as a corps commander after recovering from his wound at Chickamauga, where his division had driven home the charge that ruined Rosecrans. Eager to give Sherman the same treatment, Hood complained behind his commander's back to Richmond of Johnston's Fabian strategy.

At Cassville, Johnston finally thought the time had come to fight. But ironically it was Hood who turned cautious and let down the side. Sherman's pursuing troops were spread over a front a dozen miles wide, marching on several roads for better speed. Johnston concentrated most

44

. Lloyd Lewis,

Sherman: Fighting Prophet

(New York, 1932), 357.

45

. Samuel Carter III,

The Siege of Atlanta

, 1864 (New York, 1973), 125.

of his army on the right under Hood and Leonidas Polk to strike two of Sherman's corps isolated seven miles from any of the others. On May 19, Johnston issued an inspirational order to the troops: "You will now turn and march to meet his advancing columns. . . . Soldiers, I lead you to battle." This seemed to produce the desired effect. "The soldiers were jubilant," recalled a private in the ist Tennessee. "We were going to whip and rout the Yankees."

46

But confidence soon gave way to dismay. Alarmed by reports that the enemy had worked around to

his

flank, Hood pulled back and called off the attack. The Union threat turned out to have been only a cavalry detachment. But the opportunity was gone; the rebels took up a defensive position and that night pulled back another ten miles to a line (constructed in advance by slaves) overlooking the railroad and the Etowah River through Allatoona pass.