Battle Story (13 page)

Authors: Chris Brown

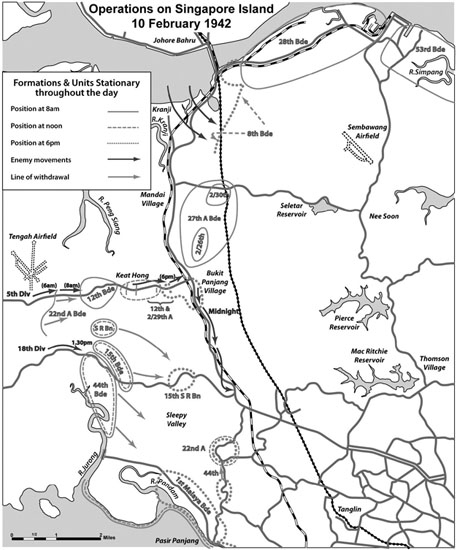

10 February |

| 2/28th and 2/30th Battalions withdraw inland toward Mandai in the early hours. |

| Tank unit attached to the Japanese Guards Regiment lands in Kranji and deployed on Woodlands Road. |

| Commonwealth forces lose the Jurong Line. |

| Wavell visits Singapore for the final time and orders a counter-attack to retake the Jurong Line. |

| The Japanese regroup most of 5th Division around Tengah Airfield and 18th Division on the Jurong Road. |

This time the Japanese did not make the kind of progress to which they had become accustomed through most of the campaign. Several of the assault craft became separated from the main body

and a number were sunk. Well-handled machine-gun and mortar fire inflicted considerable casualties on the run-in to the shore, where the attackers then encountered burning oil and petrol that had been prepared for in advance. Although losses had been heavy and the hold on the shore was not extensive, the Guards initially struggled to hang on in the face of a stout Australian defence, but as reinforcements arrived they were able to gain the initiative and after some heavy fighting were able to force 2/26th to a position about a quarter of a mile from the shoreline. This allowed for one of the few genuinely successful attempts at denying the Japanese the material prizes of Singapore to be carried out. Through the night an Australian engineering officer charged with destroying the large supplies in the Woodlands fuel tank area found himself without the necessary explosives, so he simply opened the taps and let the contents flow freely into the strait. Whether by accident or design, the fuel was ignited by small arms fire and as the tide pushed it into the streams and swamps around Kranji the burning fuel caused extensive casualties among Japanese troops.

Maxwell knew that 22nd Brigade had been roughly handled by the Japanese and was concerned that his own brigade would now become isolated. Major Oakes, who had been given command of both 2/28th and 2/30th Battalions to hold back the Japanese and to ensure the destruction of the Woodlands fuel tanks, concluded that his men were now in danger of being overrun and started to withdraw inland, away from the Kranji area and toward Mandai in the early hours of 10 February. This naturally ceded the shoreline to the west of the causeway and passed the tactical initiative to the Japanese at a critical juncture.

Impressed by the tenacity of the Australians, the commander of the Guards Division, General Nishimura, had asked permission from General Yamashita’s headquarters to withdraw his men and make a new landing the following day further to the west. As soon as it became apparent that the Australians were withdrawing, any such plan was abandoned in favour of pursuing the original objectives. Instead of having to either mount a supporting attack to relieve

the Guards detachments to the west of the causeway or even withdraw them from their small beachhead, Yamashita could now expand his position on the northern shore of Singapore. Tactically, this restricted the freedom of action of Bennett’s command and threatened the left flank of Heath’s III Corps in the Eastern Area.

Operations of 10 February 1942.

It also gave Yamashita the opportunity to exploit one of his most important assets. The tank unit attached to the Guards Division was now floated across the Johore Strait, landed in the Kranji area and deployed on to the Woodlands Road. The Guards Division could have seized the moment and made a thrust toward Singapore city, but failed to do so; however, the Allied situation was now positively perilous. Bennett’s Jurong Line had been compromised on its northern flank and the Australian division was now separated from 11th Indian Division in the naval base area. 11th Division headquarters were not made aware of the situation until about an hour before dawn. Realising that there was now a space of more than 2 miles between his own troops and the Australians that was completely unguarded against the Japanese, the divisional commander, General Key, contacted Western Area Command to ask that the situation be stabilised, only to be told that there were no units to be spared. This was the simple truth; all of the units in Western Area had suffered considerable losses, were already engaged, were too far away or, in the case of 15th Brigade, were required to provide support for units in contact with the enemy. Key decided that the only hope of restoring the situation was to secure the high ground overlooking the strait, and thus ordered 8th Indian Brigade to make a counter-attack to the north and west, and asked Brigadier Maxwell to ensure that Mandai village was occupied in order to protect the flank of 8th Brigade as they moved forward.

Throughout the 10th some semblance of order was achieved across the front, which now extended from the high ground to the east of Sungei Mandai, where 8th Indian Brigade had made some progress at heavy cost to Mandai village. Here 27th Brigade held positions overlooking the Woodlands Road, while 8th Indian Brigade progressed to a point between Bulim and Keat Hong, then south to the headwaters of the Sungei

Jurong. In just two days of fighting, the Japanese had already taken about one-third of Singapore Island, and now the situation took a marked turn for the worse. The nearest thing to a natural defensive line between the Japanese Army and Singapore city was the Jurong Line, which ran along a really rather minor ridge between the sources of the Kranji and Jurong rivers. The positions were not especially strong, but they were a good deal better than nothing and – in some areas at least – gave the Allied troops reasonable fields of fire for machine guns and anti-tank guns. Additionally, the line was relatively short and strongly manned by 22nd Brigade, 44th Brigade and 12th Brigade.

Concerned that the Japanese would be able to seize the supply dumps around Bukit Timah and the reservoirs, and deprive his command of food, ammunition and water, Percival had drawn up a plan for a strong defensive inner perimeter with zones and tasks allotted to specified formations. Brigadier Maxwell received the instructions and then totally misunderstood them. Rather than seeing them as instructions for a planned withdrawal to the new line at the last possible moment, he and his staff construed Percival’s orders as instructions to retire at the earliest opportunity. Consequently, Maxwell set out to examine the new positions with a view to allotting roles to the units under his command. En route he visited General Bennett’s headquarters to inform his commander of his progress only to be told – in no uncertain terms – that he had utterly misread the situation. Bennett was furious with his subordinate, but, incomprehensibly, did nothing at all to remedy the situation.

By withdrawing his brigade, Maxwell had thoroughly compromised the Jurong Line. Brigadier Paris’ 12th Indian Brigade, severely weakened from action during the retreat to Singapore, now came under sustained pressure from the Japanese. Unable to establish contact with the Australian 27th Brigade on his right flank or with Western Area headquarters, and concerned that a Japanese advance to Bukit Timah would isolate his brigade, Paris decided to pull back to Bukit Panjang village.

Paris’ actions were unavoidable if his units, now including elements of the Australian 2/29th Battalion, were not to be cut off, but his withdrawal left two other brigades, 44th and 15th, vulnerable to attacks on their flanks. By early afternoon a mixture of heavy fire from the Japanese and an unfounded report that a neighbouring British battalion had withdrawn caused various elements of 44th Brigade to make an unauthorised retreat that Brigadier Ballentine was able to bring to a halt, but only at the cost of concentrating his men at Pasir Panjang. At this point he was able to make contact with Southern Area headquarters and was told to take his brigade to a location at the Ulu Pandan, about 1 mile south of Bukit Timah.

The entire Jurong Line plan was now utterly redundant. To the south, 1st Malaya Brigade (Brigadier Williams) was now exposed on its northern flank and was obliged to retire to Pasir Panjang on the south coast, and in the Northern Area, Brigadier Coates’ 15th Brigade was forced to retire to a new position on the Jurong Road, where they were joined by the Australian Special Reserve Battalion. Although the Jurong Line was far from being a thoroughly prepared position, it had been reconnoitred, some fire plans had been made and some defences erected. It was certainly the only feasible defensive line to the west of Singapore city, but it had been effectively abandoned by about 1800hrs on 10 February. After less than two days of fighting, nearly one-third of Singapore Island was in Japanese hands and several of Percival’s brigades – 12th, 15th and 44th Indian and 22nd and 27th Australian – had suffered substantial casualties and were close to exhaustion.

The fighting had taken its toll on the Japanese as well, but they were now firmly established on the island. The nature of the terrain and the infiltration tactics employed had resulted in several units becoming quite scattered, but by the evening of the 10th the Japanese had been able to regroup most of 5th Division and some tanks around Tengah Airfield. At the same time, 18th Division concentrated on the Jurong Road about 3 miles west of Bukit Timah and both formations were ready to renew the fight.

On the afternoon of 10 February, Wavell, making his final visit to Singapore, met Bennett at Western Area headquarters and was informed that the Jurong Line had been taken; though to a great extent it had really been abandoned. Wavell ordered Bennett to mount a counter-attack to recover the Jurong positions at the

earliest opportunity. If successful, it would provide a focus for the defence of the rest of the island and a barrier behind which the infantry units could be regrouped, replenished and rotated, and where artillery batteries could be sited. Without the Jurong Line there was no realistic prospect of halting the Japanese and a plan of sorts was formulated in which 22nd Brigade to the south, 15th Brigade in the centre and 12th Brigade to the north, with the support of two regiments of field artillery and with 44th Brigade in reserve, would regain the Jurong Line. The first step of the attack would take place before 1800hrs that day. The problem with the scheme was that none of the formations involved were fit for an advance at all. By chance – and nothing more – they happened to be in relatively convenient locations for the tasks allotted, but

losses in men, transport and communications, exhaustion and local shortages of ammunition and water meant that there was no realistic prospect of mounting a successful attack without bringing large numbers of fresh troops into the battle. Additionally, the plan gave precious little thought to the practical difficulties of moving a large proportion of the attacking force through the night and seemingly no consideration at all to what actions the Japanese might have in mind.

38. Forest and mountain terrain in eastern Malaya. (Author’s collection)