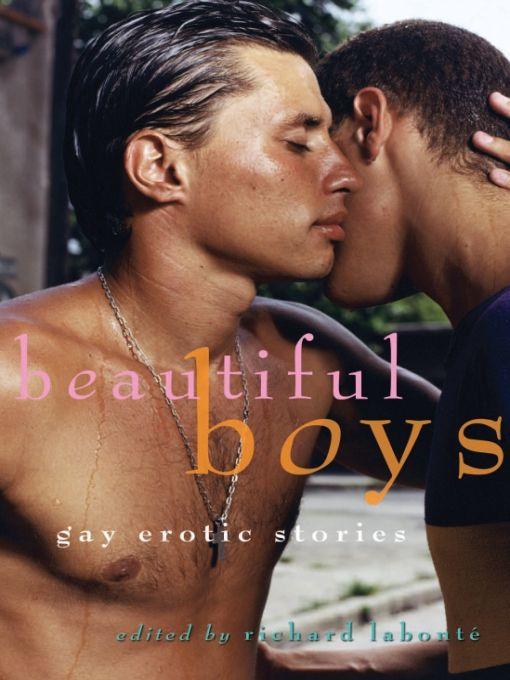

Beautiful Boys: Gay Erotic Stories

Read Beautiful Boys: Gay Erotic Stories Online

Authors: Richard Labonte (Editor)

Table of Contents

Asa,

through two decades

my Beautiful Boy Man

through two decades

my Beautiful Boy Man

INTRODUCTION: EYE OF THE BEHOLDER

Though one man’s beauty might well be another man’s beast, the reality is that queer fellows—at least stereotypically—most often place a premium on model good looks and well-toned bodies. And so it is with a few of the stories in

Beautiful Boys

: the idealized man, or better yet one man’s idealized man, depicted for your sensual delectation.

Beautiful Boys

: the idealized man, or better yet one man’s idealized man, depicted for your sensual delectation.

But I also sought stories with more than head-turning outer beauty, radiant good looks, scorching physical appeal, or the twinky youth of a porn performer. I wanted writing that depicted men whose eye-of-the-beholder magnificence was balanced by the character of the man within: cuties who were more than merely objects of desire.

And I wanted contributors to stretch the standard queer definition of beauty. For Rob Wolfsham, for example, the attraction is to scruffy lads; with Barry Lowe, the narrative is about attraction to men damaged by their perfection; in a mini-memoir, Andy Quan remembers a gym acquaintance, long lusted after, who died for his beauty; and in another mini-memoir, Dan Cullinane recalls the men he has desired, or who have desired him, men of varied beauty and even men he lived with “who I never wanted to touch.”

Beautiful boys: no one perfect size fits all.

In my domestic relationship life, beauty is almost an afterthought. I’m as likely as the next gay man to have his head turned by a stunner, and like most gay men I have my ideals—lithe body, prominent nose, reddish hair, toned muscle.

Truth is, happily, none of my long-term partners have been all that. Norman’s hair was reddish, but mostly after an application of henna. Fernando was willowy, but his nose was a treat. Rhonda, my fairy-named love, has grown into the kind of man he fancied when we met—chubby is the affectionate term of choice. And Asa, a laborer all his life, arrived in my home toned and tall, but shorn of hair. Together they, and assorted boyfriends along the way, add up to a composite of my ideal guy. But their shared appeal for me was (and is) a singular inner beauty, the best aphrodisiac of all, the basis for our being united (serially) in love over four decades.

Beautiful men: they come in all shapes and sizes. That’s real life.

Richard Labonté

Bowen Island, British Columbia

Bowen Island, British Columbia

THE RAFT RACE

Phillip Mackenzie, Jr.

Jim walked over to the fire and tossed a load of branches onto it, and sparks rocketed through the cold night toward the wash of the Milky Way above. I was talking to Noah, my back to the fire, and I jumped about a half foot in the air and yelled, “Fuck me,” right into his face. He laughed, and we turned around to face the fire, and through the flames and smoke, one of his little girls in his arms and a leather hat pulled down over his brow, I saw the only guy I ever loved.

Twenty years on and nothing in common but a childhood tossed into the years, I wondered if I should even bother saying hello. But Richie saw me, too, and he chucked his chin in my direction and set the little girl down. April, I think someone had told me her name was. I had heard that he and his wife had moved down to Portland for a couple of years, had a few more kids and then moved back up to Idaho where opportunities were scarce but the faces were familiar.

We grew up here, on adjacent pieces of land. Our mothers hewed to this place with the fervor born of the back-to-nature movement of the sixties and seventies. Richie had a twin brother, Joey, and the three of us clung together as we survived all manner of well-meaning progressive experiments, like home-schooling, self-sufficiency farming, organic gardening and goats’ milk. When we hit adolescence we begged to be normal.

Joey was as still and watchful as Richie was restless and watch-spring wound up. Goofus and Gallant brought to life, when Richie and I would stroll out the door of the Safeway, our pockets and pants fronts stuffed with Cadbury bars and

Mad

magazines, we would find Joey waiting, twisting with remorse at our bad behavior.

Mad

magazines, we would find Joey waiting, twisting with remorse at our bad behavior.

We came off our farms at fourteen and uncertainly joined the world. High school was like a foreign country to us. By our sophomore year, Richie was downing two or three beers behind the wheel of his pickup, as the three of us rode the gravel road to school buzzed and hypersensitive. He picked fights almost every day. Joey and I made excuses to the people he punched out or puked on, and we laughed with him to make him feel like he was okay, but it didn’t get any better, and after awhile I started making up excuses about other things I had to do, and after awhile I did have other things to do.

Joey stuck by Richie and looked at me with big hurt eyes as I drifted away from them. We sat on the sagging old gate in their barnyard one night, our breath coming out clouds in the cold, and I told him that Richie scared me. “He scares everyone, Joey. People think he’s nuts. They think he’s dangerous, and they think he’s a drunk.”

Joey just smiled. “He’s okay.”

When we passed each other in the hallway at school, Richie and I would nod or say hi, but not much more. Every time it happened was like a kick in the stomach, but when you’re the one who started the kicking, how do you stop it?

I stopped growing in my junior year, but Richie and Joey got bigger and bigger. They worked summers when they could for one or the other of the logging outfits in town. They struggled through brush on steep hillsides setting cables on felled trees, which would be yanked upward by winches. The work was brutal and dangerous, and I pictured them doing it: Richie crashing through undergrowth like a bull, with Joey behind him trying to keep him safe.

By our senior year, they were both over six-four; standing side by side in the hallway, their shoulders almost touched the lockers lining the walls. They should have played football, but the coach was afraid Richie would kill someone, and Joey wasn’t going to go where his brother wasn’t wanted. That whole year, I barely spoke to them. Richie was lost to something I couldn’t understand, and so it was easier to let him go. But Joey broke my heart.

I saw them at graduation. Our moms forced us together for a photograph, me in the middle, the brothers towering over me, their massive arms over my shoulders. I never saw the picture. A few weeks later, Joey called.

“We’re gonna do the raft race this summer,” he said, the question hanging but not asked.

I wanted to say yes. I knew I would say yes. But I wasn’t sure if he’d ask, and it seemed like way too much to assume.

“We could use some help. You know, a third guy to help steer,” he paused, “Or build. You know.”

I suppose he was hoping that if the three of us did something together, like back when we were eleven and tried to build a cabin up in the woods above the dairy farm, it would make the last four years disappear. I suppose I was hoping for the same thing, because I said yes.

The raft race was pretty badly named, because the rafts barely floated, and they sure didn’t race. But it was the kickoff event for Kootenai River Days, the town’s annual summer festival. About fifty teams of local guys whacked together a flotilla of crappy rafts and drifted ten miles or so down the Kootenai in a long drunken party, until whoever still had a raft holding together long enough to accidentally drift into town first was declared the winner. Sometimes there was a guy who took it seriously and paddled like a Harvard oarsman, but everyone just laughed at him until he relaxed. It’s not like there was a prize. I think the winner got a hundred dollar gift certificate to Coast to Coast or Tafts.

I should have thought about it. I should have known that Richie wasn’t doing it for fun. I should have known he had something to prove.

Richie and Joey were setting chokers for Pruitt’s and I was working up at Clifty View Nursery, so we met in the putrid dinginess of Mr. C’s on Main Street, where under-thirty drunks in training hung out to shoot pool and listen to bad covers of Eagles songs. We knocked back a few beers and then wandered down the street to the Panhandle Café for burgers.

It would be great to say it was just like old times, but that would be bullshit. Richie and I could barely look at each other. We never talked about how we had been like brothers, and now we weren’t even friends. So that fact sat in the middle of the table like a stain while we avoided each other’s eyes and talked through Joey. But from that night, a raft was born.

It turned out to be a fairly complex design of PVC piping, inner tubes and pallet wood. The PVC piping was sealed up at either end and served as the framework to hold it all together. The inner tubes were effectively caged inside this and covered with more PVC; the pallet wood was for the platform and for the railings we envisioned leaning on as we swept victoriously into town.

From the planning stage through the construction of our raft, the three of us reconnected in a way that was still misshapen. I laughed at Richie’s jokes and put up with him picking me up and bench-pressing me over his head.

Other books

The King’s Assassin by Donald, Angus

Mustang Moon by Terri Farley

French for Beginners by Getaway Guides

The Dowry Bride by Shobhan Bantwal

Confessions From A Coffee Shop by T. B. Markinson

3 Christmas Crazy by Kathi Daley

Down Low Adam by Doyle Mills by Mills, Doyle

The Loner by J.A. Johnstone

Outrage by Robert K. Tanenbaum

Crow's Landing by Brad Smith