Beer and Circus (27 page)

Authors: Murray Sperber

After doing your poll, I was amazed by how much sports occupies my college life. When I add up the time spent watching TV sports, going to games, working out, playing on my frat's teams, and then partying in conjunction with sports, it is an unbelievable 34.5 hours per week. That's almost five hours a day! Imagine what my GPA would be if I spent that time in the library studying (my GPA is high now, but they'd have to put me on a special 8 point scale).

A tour of Arizona State University places these comments in context: the school has lavish, state-of-the-art recreational facilities, including the latest exercise machines and a number of Olympic-size swimming pools; on the other hand, the library is underground, a dark, forbidding place. Predictably,

on a typical weekday, undergraduates fill the recreational buildings, and the library is deserted. At night, students pack the off-campus bars in Tempe, as they do the stadiums and arenas when the Sun Devils play at home.

on a typical weekday, undergraduates fill the recreational buildings, and the library is deserted. At night, students pack the off-campus bars in Tempe, as they do the stadiums and arenas when the Sun Devils play at home.

Another ASU undergraduate explained his sense of his institution and its beer-and-circus core:

Sometime in your freshmen year, you go through a transition where the college sports scene becomes your environment, rather than something that you observe from a distance as you did in high school, or as people who go to smaller schools do. You realize that being a Sun Devil, from cheering to drinking, is crucial to experiencing college life.

A sophomore male at ASU's main rival, the University of Arizona in Tucson, put another twist on the question of time spent in sports related activities: “I'm well over the thirty-hour-a-week mark, but a lot of it is following my bets on TV and the web.” As an earlier question on sports spectatorship discovered (Chapter 10), many male students, particularly those belonging to the collegiate subculture at beer-and-circus schools, bet frequently on college sports events, and consume many hours per week tracking the games on which they have money “down.” The next chapter of this book examines campus gambling, and also the mind-set of contemporary student fans.

Â

Â

The results of the “hours spent” questions on the survey for this book highlight a major difference between students at NCAA Division I schools and those at Division III institutions. Big-time college sports not only plays a much more important role in the daily lives of Division I undergraduates than their counterparts in Division III, but the ancillary effects, particularly time spent in sports-related activities, especially partying, indicate significant differences in student life at these schools.

An equally important contrast occurs when responses from undergraduates at Division I-A football universities are separated from those at Division III and Division I institutions not in I-A football (mainly schools with big-time basketball programs but small-time football ones). Division I-A respondents, particularly males, spent many more hours partying, watching, betting on, and playing sports than students at all other types of schools.

Most Division I-A universities contain two essential elements of the criteria that researchers use to define High Binge schools: big-time intercollegiate athletic programs and large Greek systems. Similarly, most Division III and some smaller Division I schools have Low Binge characteristics: institutions with mainly low-key college sports programs and few or no Greeks. In addition, as discussed in previous chapters, High Binge institutions tend to be large, public research universities that neglect general undergraduate education, whereas Low Binge schools are often smaller-sized private universities and colleges that attempt to provide all of their students with quality undergraduate educations.

Â

Finally, every college student in America has freedom of choice, and even at the highest binge schools, every undergraduate chooses how to spend his or her time. Sadly, far too many students at NCAA Division I-A universities devote numerous hours per week to drinking and big-time college sports entertainment. In fact, the main time difference in the responses to the “partying” questions from students at most Division I-A schools and those at all other institutions were the added hours that the undergraduates at I-A's spent drinking in conjunction with the college sports circus. In many ways, I-A student devotion to beer-and-circus is the difference between a school being a High Binge or Low Binge institution.

RALLY ROUND THE TEAMâAS LONG AS IT WINS AND COVERS THE SPREAD

T

his chapter examines the mind-set of contemporary student fans, including those who bet on college sports teams. For most undergraduates, a winning team is paramount, but for an increasing number of student fans, winning is not enough; the team must also help them win their bets.

his chapter examines the mind-set of contemporary student fans, including those who bet on college sports teams. For most undergraduates, a winning team is paramount, but for an increasing number of student fans, winning is not enough; the team must also help them win their bets.

Â

Â

One of the most annoying things about being a UConn [University of Connecticut] student is that people constantly come up to me [in my hometown] and ask all kinds of questions about the [UConn men's and women's] basketball teams, as though the only reason that I came to college was to become a screaming, drunken fan of the Husky dog [the UConn mascot]. When I politely answer that I have no time to watch basketball due to a sordid desire to graduate on time, people look at me as though I might be a hippie, or a Communist, or both.

âMatthew Decapua, in a 1999 article in the

UConn student newspaper

UConn student newspaper

This undergraduate admits to being unusual in placing academic ambitions above rooting for his college team, and, as he suggests, many of his fellow UConn students are “screaming, drunken fan[s] of the Husky dog.” The questionnaire and interviews for this book discovered a similar situation at most Big-time U's: a majority of students embrace their college teams, particularly if they are championship caliber like the UConn

basketball squads, and they fully enjoy the beer-and-circus atmosphere surrounding the teams.

basketball squads, and they fully enjoy the beer-and-circus atmosphere surrounding the teams.

However, a downside exists for universities and athletic departments: student fans, like most contemporary sports fans, are increasingly obsessed with winning, and they define triumph as not simply an “above .500 won-loss record,” but winning it allâwinning national titles. An Ohio State senior stated, “For every Big Ten champion, there are ten losers [the conference has eleven members since Penn State joined]. Anyway, league titles don't count for much anymore, it's the national championship, or you lose.”

Nevertheless, students will party on whether their team wins or loses, but often they will not support losing squads by attending games or showing any school spirit toward them. “We have an awful football program,” a Ball State University junior said. “On game days, it seems like there are more students tailgating in the parking lot outside the football stadium than inside watching the game, and there are lots of frat and off-campus parties taking place while the game is going on.”

Â

Psychology professor Robert Cialdini has long studied the fans of winning teams like those at UConn, and of losers like those at Ball State. He describes their attitudes as “basking in [the] reflected glory” of winners, and “distancing themselves” from losers. Student fans want “to associate themselves with winning teams ⦠to boost their image in the eyes of others,” especially outside their universities; and “they believe that other people will see them as more positive if they are associated with positive things, even though they didn't cause the positive things.” Hence, the Flutie Factor in applications for college admissionâthe desire by applicants to attend schools with winning college teams, even though as students at Big-time U's, they will probably never meet the athletes or coaches responsible for the victories (see chapter 6).

Equally important to the fans' psyche is the fear of failure, of their teams' losing and being called, along with them, that most dreaded of contemporary epithetsâ“LOSER.” After the 1999 football season, a University of Iowa junior male felt that he was experiencing this nightmare:

This has been an absolutely humiliating year for me. Our football team lost almost all its games and were pathetic. It's a

personal

embarrassment to me because all of my friends back home in Chicago are going to call me during [Christmas] vacation and harass me about the pitiful Hawkeyes. They're going to rag on me for supporting a bunch of losers and going to a loser school.

personal

embarrassment to me because all of my friends back home in Chicago are going to call me during [Christmas] vacation and harass me about the pitiful Hawkeyes. They're going to rag on me for supporting a bunch of losers and going to a loser school.

The Iowa student's comments reflected those of many other undergraduates. In interviews for this book, when asked whether loyalty to their university and its teams would keep them rooting through losing seasons, many students stated that loyalty was much less important to them than winning, and, if their teams became or remained “losers,” they would stop attending games or even watch them regularly on TV. But almost all said that they would “party on, win or lose,” although they much preferred victory celebrations to wakes. Moreover, as the Ball State student indicated, schools with mediocre or bad teams usually have trouble filling their football stadiums and basketball arenas; some athletic departments in this situation have even given free tickets to students and had few attend.

The contemporary college student fixation on winning was echoedâand sharpenedâby

ESPN The Magazine

when, after the 1999 men's and women's championship basketball games, won by UConn and Purdue over Duke teams, it proclaimed in its hipper-than-thou manner: DUKE UNIVERSITYâTwo teams. Two finals. No [championship] rings? Yeah, more like Loser University.'

ESPN The Magazine

when, after the 1999 men's and women's championship basketball games, won by UConn and Purdue over Duke teams, it proclaimed in its hipper-than-thou manner: DUKE UNIVERSITYâTwo teams. Two finals. No [championship] rings? Yeah, more like Loser University.'

ESPN The Magazine

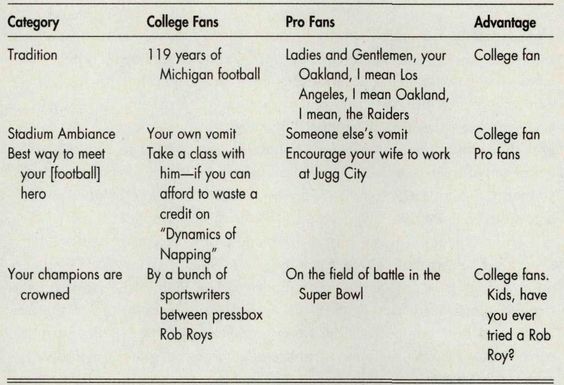

also did one of its mock gambling charts on “College [Football] Fans” versus “Pro [Football] Fans,” the entries reflecting itsâand its readersâdoublethink on college sports: it's wonderful/it's ridiculous, and even championships have questionable undersides. Among the entries were:

also did one of its mock gambling charts on “College [Football] Fans” versus “Pro [Football] Fans,” the entries reflecting itsâand its readersâdoublethink on college sports: it's wonderful/it's ridiculous, and even championships have questionable undersides. Among the entries were:

Despite elements of sentimentality about college football (“119 years of Michigan football”), the ESPN writer also mocks it: the heroes are dumb jocks and the championship game is decided by drunken sportswriters voting for the top teams. Alcohol also envelops college fans in the stands, including in their own vomit. A college football championship is great and simultaneously tarnished. But ESPN's most important message is:

As ESPN viewers and readers, you are hip to it all.

As ESPN viewers and readers, you are hip to it all.

Â

Another ESPN commentaryâand influenceâon contemporary college sports fans occurs when, during games, it focuses its cameras on students displaying various body parts painted in their school colors (other networks also spotlight the painted fans, but ESPN features them more frequently during telecasts and in clips on news shows, particularly

SportsCenter

).

ESPN The Magazine

also glorified these fans in a feature titled “War Paint.” Next to a full-page photo of a male student wearing gold paint and little else, and another photo of a male student similarly dressed in garnet (deep red) paint, the text explained:

SportsCenter

).

ESPN The Magazine

also glorified these fans in a feature titled “War Paint.” Next to a full-page photo of a male student wearing gold paint and little else, and another photo of a male student similarly dressed in garnet (deep red) paint, the text explained:

Some fans wear their hearts on their sleeves. But when Florida State meets Florida, who needs sleeves? Or sanity? Two FSU scholarsâmagna cum gaudyâdipped themselves in team colors to spur the Seminoles on to ⦠victory. Their parents now know they're getting their tuition money's worth.

Unfortunately, not only might the parents of these two FSU students question the “money's worth” of their tuition payments, but many other Americans, while watching TV shots of similar student antics during college games, might wonder whether undergraduate life is merely fun and games, and whether they should support higher education with their tax dollars and charitable donations. Indeed, public and private aid to America's colleges and universities has dropped significantly in the last few decades; probably the constant stream of images of bizarre student behavior at college sports events has contributed to this erosion of support.

ESPN constantly promotes the beer-and-circus aspect of higher education. Every Saturday during the football season, it places its

GameDay

announcing crew on location at a Big-time U and in close proximity to drunken undergraduates. As a result, every shot of its announcers' discussing the featured game as well as other games around the country includes, in the background, obviously drunk students acting rowdy or goofy. Because the ESPN

GameDay

broadcasts go on for over nine hours each weekâand drunken students always clog the background in the hopes of

being on TVâalmost every American who subscribes to cable-TV sees them during the fall. Then, in the winter and spring, the network's basketball broadcasts also place the announcers in front of frenetic, often painted students. ESPN imprints this image of undergraduate life upon the public, and also “normalizes” this behavior for students already on campus, as well as for those planning to enroll at Big-time U's.

GameDay

announcing crew on location at a Big-time U and in close proximity to drunken undergraduates. As a result, every shot of its announcers' discussing the featured game as well as other games around the country includes, in the background, obviously drunk students acting rowdy or goofy. Because the ESPN

GameDay

broadcasts go on for over nine hours each weekâand drunken students always clog the background in the hopes of

being on TVâalmost every American who subscribes to cable-TV sees them during the fall. Then, in the winter and spring, the network's basketball broadcasts also place the announcers in front of frenetic, often painted students. ESPN imprints this image of undergraduate life upon the public, and also “normalizes” this behavior for students already on campus, as well as for those planning to enroll at Big-time U's.

Most students who attended games [in the 1950s] dressed much differently than do those at today's games. Almost all guys wore collared shirts, some with ties and jackets. Girls wore blouses and skirts down below their knees ⦠. This is a far cry from the obscene T-shirts and torn jeans which some students wear to games today.

These observations came in an essay comparing college sports fans in the 1950s versus those in the 1990s. The writer included photocopies from school newspapers and yearbooks to illustrate the then-and-nows, the more formal 1950s attire contrasting to contemporary T-shirts exhibiting such statements as “Muck Fichigan,” and “Penn State Sucks, Purdue Swallows.” In addition, although 1950s rooters wanted their school teams to win and they had little patience with losing coaches and players, they did not taunt the opposing team with obscene signs and chants, nor try to distract them during play, particularly when kicking field goals and point-after touchdowns, and shooting free throws.

In another then-and-now contrast, the essayist remarked that, according to the press, fights between fans of opposing schools rarely occurred in the 1950s. This is accurate, but historically, college sports rivalries often prompted brawls among spectators, and their general absence in the 1950s was exceptional, mainly due to that era's “buttoned-down” ethos. In subsequent decades, primitivism returned to most football stadiums and basketball arenas, partly fueled by increasing undergraduate consumption of alcohol before and during games. By the end of the century, at some beer-and-circus schools, fan devolution had reached a Neanderthal stage, USA

Today

describing it in a feature article that began:

Today

describing it in a feature article that began:

ADD A THIRD CERTAINTY TO DEATH AND TAXES.

FANS BEHAVING BADLY.

FANS BEHAVING BADLY.

Â

When Florida beat Tennessee in September, 141 fans were ejected. Florida State visits the Swamp [the nickname of the University of Florida's home field] this Saturday. Trouble waits.

[The University of] Florida will increase its usual police contingent

from about 150 to 190 officers. The combustible mix of rivalry, alcohol, and hype will make their job a difficult one. It is much the same across the land.

from about 150 to 190 officers. The combustible mix of rivalry, alcohol, and hype will make their job a difficult one. It is much the same across the land.

The causes of students “behaving badly” at college sports events differ markedly from current fan misbehavior at pro games. At the latter, fans often resent the gargantuan salaries of professional athletes and consider the players fair game for verbal and even physical attacks. However, because of NCAA rules, the salaries of college athletes are not an issue for fans. The student conduct described by

USA Today

results from other causes, mainly the collegiate subculture that, with alcohol erasing inhibitions, allows members to act out their aggressions.

USA Today

results from other causes, mainly the collegiate subculture that, with alcohol erasing inhibitions, allows members to act out their aggressions.

Â

Binge drinking and brawling are dangerous ventures, but risk-taking is central to the collegiate subculture, not only in these activities but also in a more subtle but often just as hazardous preoccupation with gambling. One expert believes that betting, mainly on intercollegiate athletic events, “is probably a worse problem ⦠. on college campuses [today] than alcohol or drug abuse.” Unfortunately, unlike the drinking and drug problems, very few studies on student gambling exist, and the actual extent of the problem is difficult to measure.

Nonetheless, a large body of anecdotal evidence and some research indicate that a substantial number of undergraduates gamble regularly, and that more join them every day. In addition, of all students at American colleges and universities, males belonging to the collegiate subculture at beer-and-circus schools appear to be the most frequent gamblers. Any study of beer-and-circus must consider this topic.

Â

Â

Meet the Juice generation. For them, finance isn't a major, it's knowing how to spread $1,000 in wagers over 10 Saturday college football games ⦠. Class participation is sitting in the back of a lecture hall with Vegas-style “spreadsheets” laid out, plotting a week's worth of plays on games.

âTim Layden,

Sports Illustrated

reporter

Sports Illustrated

reporter

Other books

Cravings (Fierce Hearts) by Crandall, Lynn

Crystal Venom by Steve Wheeler

Trespassing by Khan, Uzma Aslam

Samantha James by The Secret Passion of Simon Blackwell

Beautiful Bounty (The Bounty Hunters: The Marino Bros. Book 1) by Nightingale, MJ

The Mason Dixon Line (A Horizons Novel) by Morris, Linda

The First True Lie: A Novel by Mander, Marina

Aurora by Julie Bertagna

Lemons 02 A Touch of Danger by Grant Fieldgrove

Remains Silent by Michael Baden, Linda Kenney