Read Belisarius: The Last Roman General Online

Authors: Ian Hughes

Belisarius: The Last Roman General (19 page)

Leadership

Leadership devolved upon the royal family and leading nobles. In the years preceding the Byzantine invasion the Vandals had suffered two large-scale reverses at the hands of the Moors. Appointed to the command of the war, Gelimer had defeated the Moors in battle, and begun negotiations. As a consequence, the morale of the Vandals was lifted, yet the limited experience of many of their leaders, and their reliance on the skills of Gelimer, may have left them with a serious disadvantage when compared to the seasoned and skilled leaders attending Belisarius, many of whom had served in the Persian War.

Belisarius’ political strategy

For Belisarius and the Byzantine expedition the first night ashore passed quietly. Early the following morning an episode occurred that was to surprise the troops. Some of the men left the camp and picked some fruit, without either asking permission or paying for the goods. They were immediately subjected to corporal punishment, although Procopius does not give us any details of the form this took. Belisarius used the opportunity to gather the army together and outline that he expected them to behave in a civilized manner and that they were to treat the natives well. He also gave them the reasons for his demands: although the Vandals had been in control of the native ‘Libyans’ for almost a century, the Libyans were still Roman at heart; he was relying upon their active cooperation as spies, scouts, guides and a source of provisions. Actions such as theft would alienate the natives and encourage them to wholeheartedly join the Vandals. In that eventuality, the Byzantines would be in grave danger (Proc,

Wars,

III.xvi.1–6). The affair not only let the troops know what Belisarius expected from them, it also gave them viable reasons for his expectations. From this point forwards, the behaviour of the Byzantine troops towards the natives was to be exemplary.

Almost as if to prove the point that good conduct would encourage native support, Belisarius now sent a contingent of

bucellarii,

under an officer called Boriades, to the town of Syllectus. Approximately one day’s march from the camp on the road to Carthage, the town would be a test of the natives’ willingness to join the Byzantines. With strict instructions not to harm the inhabitants, Boriades and his men spent the day travelling to Syllectus and then passed the night camped outside the town. On the morning of the third day, they gained entrance by the simple ruse of joining a group of wagons going into the town. When the citizens became aware of what had happened, they willingly submitted to Belisarius – although the presence in their town of Byzantine troops left them with few alternatives.

The Vandals had maintained the Roman practice of sending urgent messages using fast couriers. These men changed horses kept at staging posts, positioned at regular intervals along major roads. The overseer of the public post, who maintained at least one of these staging posts, deserted to the Byzantines. At this point one of the actual messengers was captured. He was allowed to go free and paid to distribute a message from Justinian to the Vandal people. This stated that Justinian was not intending to make war on the Vandal people, only on the man who had imprisoned their rightful king. This attempt to divide the Vandals was to fail; the messenger only showed the message to a few people that he could trust, since he was afraid of the consequences should he be captured distributing propaganda and handed over to Gelimer (Proc,

Wars,

IILxvi. 12–15).

Gelimer’s Response

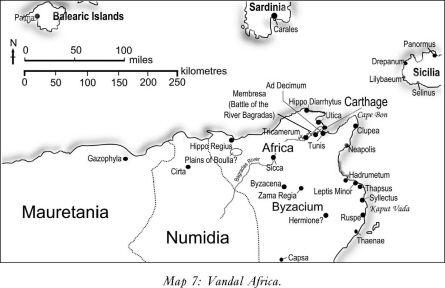

At the same time as Belisarius was making tentative moves to befriend the natives, Gelimer was moving to counter the Byzantine threat. Gelimer instantly concluded that the Byzantine army would travel along the coastal road, so passing through the valley at Ad Decimum. According to the instructions that he had already sent to his brother Ammatus, the troops in Carthage began to mobilise ready to march towards Ad Decimum from the north. Gathering a force from the area of Hermione, Gelimer marched north to rendezvous with his brother at Ad Decimum.

The Deployment of Belisarius and his march towards Carthage

Waiting for news from Syllectus, Belisarius organised the army for the march on Carthage. Three hundred

bucellarii

were placed under the command of John the Armenian, Belisarius’

optio

(‘choice’: in charge of Belisarius’ finance), with instructions to scout the way forward and report any enemy activity. He was to remain at least twenty

stades,

approximately

2⅓

miles, ahead of the main force.

*

The 600 Huns under Sinnion and Balas were ordered to guard the left flank in a similar manner to John, also remaining at least twenty

stades

away from the main force.

Belisarius stationed himself in the rear, along with his

bucellarii

and

cotmtatus,

his best troops. Aware that Gelimer was last reported as being in the south of the country, this position would enable Belisarius to immediately take close control of the troops who would be under threat if Gelimer was to arrive and attack the Byzantines from the rear. Furthermore, with his mounted

bucellarii

in attendance, he would be able to advance instantly if there was a need to support any troops further forward who came under attack.

The rest of the army marched in the centre. The fleet was ordered to keep pace with the infantry as they moved along the coast road. No flank guard was placed upon the right flank as this was resting for the most part within sight of the sea and so was protected by the fleet.

The main army now advanced to Syllectus, where the men acted in such an excellent manner that the citizens decided to give their full support to Belisarius’ venture. Furthermore, word of the restrained behaviour of the troops now paved the way for a peaceful advance towards Carthage, with the full cooperation of the towns and cities along the route.

Marching at a rate of eighty

stades

(approximately 9 miles) per day, the army advanced towards Carthage, staying at the towns of Leptis and Hadrumetum along the way. Finally, they came to Grasse, 350

stades

(around 40 miles) from

Carthage, where the Vandal king had a palace. Although Belisarius realised that the Vandals would be close, their strength and position was as yet unknown. This was now to change. As the army prepared to settle for the night at Grasse, a detachment of the Byzantine rearguard clashed with some troops sent ahead by Gelimer. After a brief skirmish, both parties retired to their camps, but Belisarius was at last certain that at least some of the Vandals were in the vicinity and closing in behind him

Belisarius was now faced with the most dangerous part of the journey to Carthage. The road ran inland while the coast curved away to the north, forming the headland of Cape Bon. This meant that the fleet would have to sail out of sight around the Cape. Unable to keep close control of the fleet, he instructed Archelaus, the prefect, and Calonymus, the admiral, to take the fleet around the headland, but to remain at least 200

stades

(c.22 miles) from Carthage. Maintaining the army’s deployment as before, he set out on the morning of the fourth day on his way towards Ad Decimum. With the absence of the fleet, he had a maximum force of around 18,000 men.

The Strategies

There is no reference to the numbers of troops available to either Gelimer or his brother Ammatus at the approaching battle. With the whole army mustering, at the most, 20,000 men, due to losses in the wars with the Moors, and with 5,000 of the best men in Sardinia under Tzazon repressing the rebellion, this leaves a maximum of 15,000 men for Gelimer. Whether he was able to muster the total force is questionable. It is more likely that he had approximately two thirds of this number available, possibly 10,000 – 12,000 men. Yet even if he could have mobilised the whole available force, his tactics are likely to have remained the same; he would never have significantly outnumbered Belisarius.

Furthermore, Gelimer would still have had a major obstacle to overcome. He would find it difficult to unite his armed forces. The Byzantines were marching towards Carthage and so forming an obstacle between the south and the north. Gelimer needed a victory at Ad Decimum in order to unite his troops.

It seems likely that the majority of the troops were led by Gelimer, since otherwise he would not have had the confidence to detach Gibamundus with 2,000 troops, as will be seen later. The number of troops available to Ammatus is also unknown, but it is possible to estimate their strength. Procopius states that they were marching in groups of no more than thirty. If we allow one group per 50 yards, this computes to around 1,000 men per mile. Allowing that Ad Decimum was 8 miles from Carthage, this gives a maximum of around 8,000 men on the road. The actual figure would be significantly lower than this: the troops had to be at Ad Decimum and deployed for battle by the early afternoon, and so would have left Carthage long before noon. Consequently, they would not occupy all of the 8 miles.

The number of troops available helps to explain Gelimer’s plan for an ambush at Ad Decimum. With only 5–6,000 men himself, and with Ammatus having only around 6–7,000, he did not have the forces to face Belisarius in a pitched battle. He did, however, have enough men to mount an ambush that could potentially destroy the Byzantine army, or at least reduce their numerical superiority and weaken their morale. Furthermore, his experience of warfare against the nomadic Moors may have predisposed him to use an ambush as a natural form of warfare.

Ad Decimum was 70 stades (around 8 miles) from Carthage. According to Procopius, the road passed through a ‘narrow passage’ (Proc,

Wars,

III.xvii.ll) and this is where Gelimer planned to ambush the Byzantines. The plan was simple: Ammatus was to move his troops from Carthage and block the northern exit from the valley. Once the Byzantines arrived, he was to attack the head of their column and drive it back into the valley, hopefully causing confusion and disorder, possibly even forcing Belisarius to commit his reserves. Whilst this attack was going in, Gelimer was to advance from the south and attack the Byzantines from the rear. With the extra confusion and dismay at having to fight in two directions, the Byzantines would then be annihilated and the war won.

The plan was elegant and simple, but there was one drawback: a lot would depend upon the timing of the attacks and they would not be easy to synchronize. According to Procopius, there were three roads in the vicinity

heading towards Carthage, none of them visible from each other due to the hilly terrain. Coordination would be extremely difficult.

The first road was the coastal route being used by the Byzantines, which passed through Ad Decimum before heading towards Carthage. Gelimer had predicted that the Byzantines would use this road, since they needed to remain in contact with their fleet. His assumption had been proved correct when his scouts had made contact on the road the previous night. Ammatus would also use this road, but approaching from the opposite direction

The centre road was the one that came up from the south, and so was the one that Gelimer was using for his advance from Hermione. This road intersected the coastal route shortly before the pass at Ad Decimum. This piece of local knowledge had determined Gelimer in his desire to fight at Ad Decimum: the Byzantines would not know that the road from Hermione intersected the coast road here and so would be taken by surprise at his unexpected appearance at the junction.

It was the third road that was to cause Gelimer anxiety. This was further inland and bypassed the valley at Ad Decimum, following a separate route towards Carthage. If Ammatus was to follow Gelimer’s instructions, Carthage would be left defenceless. With Sardinia and Tripolitania in open rebellion, Gelimer would have distrusted the natives. Even a weak Byzantine force advancing down this road would be unopposed and the Carthaginians were likely to open the gates to them. Winning a battle at Ad Decimum would be negated if Carthage itself was in enemy hands, since this could easily provoke more areas to rebel. Accordingly, Gelimer changed his plans and sent his nephew Gibamundus on to the road to ensure that Carthage remained secure. The diversion of 2,000 men away from the battle was a small price to pay to ensure that the city remained in Vandal hands. The move would also allow Gelimer to change his plans if it revealed that either the main body or at least a large detachment of Byzantine troops had already reached this road and were advancing upon Carthage, having bypassed his intended ambush at Ad Decimum.