Belle (10 page)

Authors: Paula Byrne

Dido’s illegitimacy placed her in a more awkward position, though as far as Lord and Lady Mansfield were concerned, she still had Murray blood running through her veins. ‘Natural’ daughters were a common fact of Georgian life, and there was much less stigma attached to illegitimacy than would be the case in the Victorian era. Novels and plays abounded with beautiful ‘natural’ daughters estranged from their families.

We know this from Jane Austen’s warm and humorous depiction in

Emma

of the illegitimate young Harriet Smith, who is deposited in a boarding school by her father and befriended by the wealthy, well-born Emma Woodhouse. Several of Austen’s early works of fiction, written when she was a young girl, parody the clichéd trope of a ‘natural’ daughter who sets off in search of her father, and discovers that she is the child of a wealthy aristocrat. In Dido’s case, no such measures were necessary. She knew that her father was a Murray, and a highly respected naval officer: in 1770 Captain Lindsay was appointed a Knight of the Bath.

There is no evidence that Lindsay ever returned to see his daughter, but he had ensured that she was raised in the best of hands. One wonders if Dido ever considered the fate of her mother, Maria. Every time she looked in a mirror she would have been reminded of her ancestry. Yet she was a ward of Lord Mansfield, living a life of luxury and privilege.

What was her status in the household? Once again, Jane Austen’s fiction can perhaps give us an idea. In

Mansfield Park

, the young Fanny Price is taken from her crowded and chaotic home to be raised in her relatives’ elegant country house. Her status is somewhat uncertain. She is a niece of Sir Thomas Bertram, and ‘must be considered so’, but she is certainly not a ‘Miss Bertram’, a daughter of the house. She comes to occupy a status above that of a servant, but below that of a fully

bona fide

family member. An unpleasant aunt, Mrs Norris, never hesitates to remind her of her inferiority and her (undeserved) good fortune in being taken into the great house. As it happens, the low-born Fanny Price becomes the most loved and cherished ‘daughter’ of Sir Thomas Bertram, and marries his younger son.

In certain respects Fanny’s story echoes that of Dido. While Lady Elizabeth was the daughter of the heir to the title, and a legitimate Murray, it is Dido who appears to have captured Lord Mansfield’s heart.

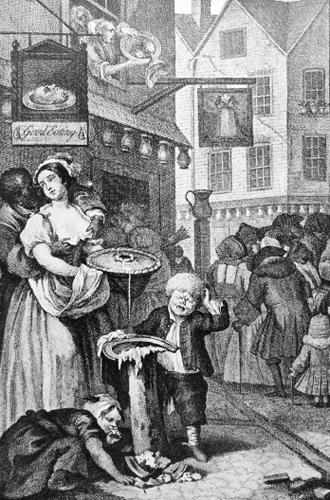

Detail from ‘Four Times of the Day: Noon’, engraving of a London street scene by William Hogarth, showing, to the left, an amorous black London resident

Baptised in Bloomsbury, Dido Elizabeth Belle was an authentic London immigrant. Contrary to the popular image of London as all-white before the mass immigration of the years after the Second World War, there were about 15,000 black people living in the city in the late eighteenth century.

1

Their traces are visible in portraits, caricatures, literature, newspapers, and on the stage of the London theatres. Moreover, they were creating their own cultural identity, forming musical societies, joining church groups, holding exclusive ‘Black Balls’, writing their memoirs and forming support groups for runaways. There were stories of noble African princes who had come to England for their education and been betrayed into slavery, and of servants who had escaped their brutal masters and were seeking their freedom. There were all-black brothels, which catered to the nobility.

2

The black community was the subject of news, and was gossiped about in polite society. Its members were a vital presence in London, and they were not going to go away.

Maria could have ended up in this world, but her daughter Dido would never be a part of London’s black community. She was assimilated into upper-class white society, and carefully protected by the Mansfields. But being well educated, she could read newspapers and books, and attend plays. As she travelled back and forth between Bloomsbury and Kenwood House in her uncle’s fine carriage, she would have been able to look out of the window and see liveried black servants attending to their masters and mistresses.

Strangers who saw Dido when she was a child would have assumed that she was a servant. Eighteenth-century portraits often included little black page boys or alluring African serving girls. In some quarters a black attendant was viewed as a must-have fashion accessory, like an exotic ostrich feather in one’s hair. Ladies of quality adored black servants, especially as their blackness accentuated their own white skin, which was invariably leadened to make them look even whiter. Black children were seen as adorable pets, and dressed in brightly coloured silks and satins with turbans. Little surprise that when they grew older and lost their ‘cuteness’ they were often sold back into slavery, and sent to work on plantations.

3

The Duchess of Queensbury – said to be the most beautiful woman in Europe – was devoted to her ‘young Othello’, a black servant called ‘Soubise’. She educated him to a high standard, pampered him, taught him to ride and to fence, to play the violin. He was taught oration by no less a master than David Garrick, the greatest actor of the age. Spoilt and reckless, Soubise grew up to become a noted dandy, seducing women and running up enormous debts, which were always paid off by the doting Duchess. One of the people she appealed to for help in trying to discipline him was Ignatius Sancho, the best-known black man in London.

Sancho, perhaps like Dido, was born on a slave ship. He became butler to the Duke and Duchess of Montague, and was a well-read, intelligent and articulate man – because of his corpulence he jokingly called himself ‘the black Falstaff’. He made his name as a writer and composer, eventually becoming a property-owning householder in Westminster, which entitled him to vote. His

Letters

were published after his death, and bear testament to his education. He was a great favourite of Garrick, and corresponded with Laurence Sterne and other notable writers and intellectuals. Sancho was fiercely opposed to the slave trade: ‘the unchristian and most diabolical usage of my brother Negroes – the illegality – the horrid wickedness of the traffic – the cruel carnage and depopulation of the human species’.

4

He gained a degree of acceptance in London society, but was always regarded as a curiosity: when he visited Vauxhall pleasure gardens with his black daughters, he wrote, ‘we went by water – had a coach home – were gazed at – followed, &c &c – but not much abused’.

5

Sancho married a West Indian woman of African descent. A mixed-race marriage across the class divide would have been a breach of propriety that would have cost him his position as a kind of black mascot for white society. When it came to relations between the races, there were strict barriers. A black footman might marry a white maid, for example, but not a cook.

6

In the comic opera

Inkle and Yarico

, the inter-racial love affair between the two main characters is mirrored by that between Inkle’s servant Trudge and Yarico’s servant Wowski. Though Inkle rejects Yarico because he is ashamed of her, and tries to sell her into slavery, the lower-class Trudge is fiercely loyal to Wowski: ‘I won’t be shamed out of Wows. That’s flat.’

In London life, as on the London stage, marriage between black and white was acceptable so long as it did not cross the class divide. There was a profound cultural fear of black sexual potency: hence the fascination with the figure of Shakespeare’s Othello, the Moor who came from North Africa to Venice. At a more mundane level, casual racism abounded. Black people were routinely represented as having voracious sexual appetites: William Hogarth’s engraving of a London street scene at noon shows a black man groping the exposed breasts of a serving girl outside a tavern.

The limits of what was possible for even the luckiest and most talented people of colour in late-eighteenth-century European society may be illustrated by the case of Joseph Boulogne, Le Chevalier de Saint-George, which would have been well known to Lord Stormont during his time as Ambassador to the court at Versailles, when his young daughter Elizabeth was being brought up with Dido. Saint-George was a handsome, elegant, cultivated young man. A superb sportsman, he was regarded as France’s finest fencer, a gifted equestrian, and renowned for such exploits as swimming the Seine using only one arm. He was also a musical virtuoso, playing the violin as a child on the French Caribbean island of Guadeloupe. Like Dido, Saint-George was the product of a union between a slave mother and a well-born father. And as with Dido, his father had him brought up as an aristocrat, but did not marry his mother.

He rose to become a composer and conductor, and taught music to Marie Antoinette. He commissioned Joseph Haydn to compose six major pieces, at a time when Haydn was struggling to find work. Louis XVI named him director of the Royal Opera, though he was forced to revoke the appointment after protests from singers who refused to perform under the direction of a ‘mulatto’.

7

He became known as ‘

le Mozart Noir

’, writing five operas, twenty-five concertos for violin and orchestra, string quartets, sonatas and songs. He was given equal billing with Mozart when his concerts were advertised.

Women adored Saint-George, and rumours abounded about his close relationship with Marie Antoinette. According to gossip, his pillow was stuffed with the pubic hair of his numerous lovers. But he never married, as inter-racial marriage was banned in France. After the Revolution his connection to the royal court made it difficult for him to find work, and he died in obscurity in 1799, at the age of fifty-four.

There were far fewer black women than men in England. Servitude or prostitution was their usual fate. Dido was in every way the exception to the rule. Despite the few such as Soubise and Ignatius Sancho who successfully assimilated into English society, the majority of black people living in London were poor, and denied the most fundamental of rights.

One such young black man was Jonathan Strong. Like many Africans living in London, he had been brought to England from a sugar plantation (in Barbados) with his master. In 1765 Strong was beaten half to death by his owner, David Lisle, and thrown onto the streets. He had been pistol-whipped about the head, and was almost blinded. Stumbling to a doctor’s surgery in Mincing Lane, he met the doctor’s brother, Granville Sharp. This chance encounter would change Sharp’s life, being instrumental in making him one of the leading lights of the abolition movement, and thus transforming the lives of thousands of black people in England. It would also bring him face to face with one of the most powerful men in the land: Lord Mansfield.

William Murray, later the first Earl of Mansfield, portrait by Jean-Baptiste van Loo, which in Mansfield’s will he asked to be hung in Dido’s room

Lord Mansfield was an innovator. Over his long tenure of thirty-two years as Lord Chief Justice, he modernised both English law and the English court system. His rulings changed English and Commonwealth nations forever, and he was also a strong influence on the laws of the United States of America.

1

His influence cannot be overestimated.

Mansfield’s great hero was the ancient Roman lawyer, philosopher and orator Marcus Tullius Cicero. He would, for pleasure, translate Cicero into English and then back into Latin, and he memorised volumes of his works. Cicero had said that ‘True law is right reason in agreement with nature; it is of universal application, unchanging and everlasting.’ In the full-length portrait of Mansfield that now hangs in the hall of his

alma mater

, Christ Church, Oxford, his hand rests on a copy of Cicero.