Belle (6 page)

Authors: Paula Byrne

Cowper was writing at a time when the abolition movement was under way. Previously, few people stopped to consider that England’s addiction to sugar came at a terrible human cost. When the women of England purchased their hard white phallus of sweetness, they probably wouldn’t have known that it was once sticky, black, viscous molasses, refined to look and taste palatable, stripping it of its nutrients and vitamins.

Sugar growers had discovered that cane was best grown on relatively flat coastal land where the soil was naturally yellow and fertile, and the temperature mild and sunny. The Caribbean provided the ideal climate and conditions. In the last decades of the eighteenth century, four-fifths of the world’s sugar came from the British and French colonies in the West Indies.

7

From Barbados, Jamaica, Martinique, Grenada, Saint Croix, the Leeward Islands, St Domingo, Cuba, Guyana and many others. As Europeans established their sugar empire in the Caribbean, prices fell, especially in Britain.

Sugar cane was produced on plantations, which were large-scale, artificially established terrains. After being harvested, the cane was taken to purpose-built distilleries where it was crushed, boiled and refined, then packed into barrels to be shipped to Europe. This was demanding, backbreaking work, carried out in the harshest of conditions.

Over the decades, the sugar plantations became larger and larger. Wherever sugar could be grown, there was a need for a labour force – a labour force that was strong and numerous, that was resistant to diseases such as yellow fever and malaria, that could work well in the heat and humidity. African slaves – men, women and children – became the dominant source of plantation workers.

Jamaica was one of the largest and most brutal slave societies of the region, and the most productive of the sugar islands. In 1805, Jamaican sugar production peaked at over 100,000 tons for the year. The island was the jewel in Britain’s Caribbean crown. This came at a price.

The death rate for black slaves in Jamaica was higher than the birth rate.

8

The main causes for this were overwork and malnutrition. Field slaves worked from four in the morning to sundown, in blazing heat. The workforce on each plantation was divided into gangs determined by age and fitness. On average, most estates had three main field gangs. The first comprised the strongest and most able men and women; the second those no longer able to serve in the first; and the third older slaves and older children. Some estates had four gangs, depending on the number of children, who started working as young as three or four years of age.

9

The field slaves were required to cut down the canestalks, which were two inches thick and up to fifteen feet high. The field slaves were supervised by demanding masters, who gave them little medical care and beat them indiscriminately. They were flogged if they failed to work quickly enough. They were flogged if they were discovered sucking the calorific, sweet sap released by the cane when it was cut. No allowances were made for pregnant women or those with tiny babies strapped to their back. Life expectancy for a field slave was seven years.

10

The cane had to be milled quickly before its sap dried out. It was taken to the crushing mill, where it was hand-fed into huge rollers to squeeze out the dark-brown juice, which then flowed through a trough into the boiling house. It was repeatedly boiled to remove impurities before being poured into cooling tanks. The next stage was to pack the sugar into hogsheads or earthenware cones to dry and crystallise in loaf form. The molasses dripped through a hole at the bottom of the barrel or cone, leaving the sugar purer, and of course paler. The golden sugar would then be packed into hogsheads for exportation. Once in England, it was further refined and whitened by ‘claying’, a process whereby it was cured in ceramic moulds with clay tops. The moisture seeped through the cones, leaving the muscavado pure white, and shop-ready.

11

The Caribbean boiling houses were extremely dangerous for the (usually female) workers in them. The clarification process involved heating and reheating the sugar at ferocious temperatures, and many slaves were scalded and burnt. Often they worked eighteen-hour days, becoming so tired that as they fed the cane through the huge rollers they could be dragged into them and crushed to death. Overseers kept a machete handy so they could hack off trapped limbs. As a result many slaves had missing hands or fingers. In Voltaire’s

Candide

(1759) a maimed slave explains, ‘When we work in the sugar mills and we catch our fingers in the millstone, they cut off our hand; when we try to run away, they cut off a leg; both things have happened to me. It is at this price that you eat sugar in Europe.’

12

Again we must turn to Mary Prince, whose

History

gives a unique account of plantation life from the perspective of a female slave. As a house slave on a Bermuda plantation, she was frequently abused by her owners. ‘To strip me naked – to hang me up by the wrist and lay my flesh open with the cow-skin [whip], was an ordinary punishment for even a slight offence.’

13

Usually the floggings were administered by slave foremen called ‘drivers’, who were often related to the workers they were called upon to punish. Mary Prince wrote of the particular horror when a driver would ‘take down his wife or sister or child, and strip them, and whip them in such a disgraceful manner’.

14

One of the most extensive and disturbing accounts of plantation life can be found in the journal of Thomas Thistlewood, who as we have seen lived with his black slave Phibbah as his ‘wife’ for over thirty years. An inveterate diarist and note-keeper, he left over a million words detailing his life in Jamaica from 1750 to 1786. They build a day-to-day picture of plantation life, of what it was like to be a British owner living with his sugar slaves. Thistlewood was educated and well-read, arriving in Jamaica with the poets Milton, Chaucer and Pope, and the essayist Addison in his luggage, and continuing to build his library during the years in which he lived there. In preparation for his life as an overseer he read a manual by his neighbour, Richard Beckford, about how to manage a sugar plantation. Beckford was the biggest sugar baron in the West Indies, owning more than a thousand slaves. His manual advised that it was best to treat slaves with ‘Justice and Benevolence’, but he also warned about the need to guard against insurrection. Thistlewood took more heed of the latter than the former advice. He was told by other sugar planters to take a tough line with his slaves, and in his early days he was sent the severed head of a runaway slave to display as a warning to his field gangs.

In just a short time, Thistlewood became acclimatised to the planter’s way of life. Showing none of Beckford’s proposed ‘Justice and Benevolence’, he brutalised and tortured his slaves, flogging them for insubordination, rubbing lime juice, pickles, salt and bird pepper into the gashes for added effect. In order to prevent them from sucking the sweet cane juice, he devised a sickening punishment that he called ‘Derby’s Dose’. ‘Had Derby well whipped,’ he records in his journal, ‘and made Egypt [another of his slaves] shit in his mouth.’

15

He sexually exploited his female slaves, keeping a detailed account of every encounter in schoolboy Latin. ‘Last night

Cum

[with] Dido’ was one of his typical diary entries. (This is not our Dido – the name was commonly given to female slaves.) Thistlewood’s journal shows how institutional violence characterised sugar plantations, how slavery brutalised everyone.

16

But there was another side to him, which was developed when he fell in love with Phibbah and became the father of a mixed-race boy. His relationship with Phibbah sheds light on the highly complicated matter of inter-racial pairings.

Thistlewood’s sugar plantation was in the south-east of the island. He would probably have known Sir Thomas Hampson, who also owned a plantation in Jamaica. Hampson was Jane Austen’s cousin twice-removed,

17

and the shadow story of her novel

Mansfield Park

, in which Sir Thomas Bertram owns a sugar plantation in Antigua, is the slave trade. Many people in Georgian England were connected in some fashion with West Indian plantations.

Indeed, the character of the West Indian planter became a staple in British fiction and drama during the period. One of the most popular comedies on the eighteenth-century stage was Richard Cumberland’s

The West-Indian

(1771). Its hero, Belcour, is a wealthy young scapegrace fresh from his sugar estates in Jamaica, ‘with rum and sugar enough belonging to him to make all the water in the Thames into punch’. His entourage includes four black slaves, two green monkeys, a pair of grey parrots, a sow and pigs and a mangrove dog.

The fine ladies and gentlemen of England piled into the Theatre Royal Drury Lane to see the exploits of this kind-hearted fictional sugar baron. They would have laughed at his bewildered account of arriving from Jamaica at a bustling English port crammed with sugar casks and porter butts. Belcour is depicted as a harmless libertine, who chases English girls until he is as thin ‘as a sugar cane’ – the mild stage image of such a man was a far cry from the reality of Thomas Thistlewood, with his rapes, his floggings and his sadistic punishments.

Georgian high society was a world away from the sugar islands, where all that mattered was efficient production on the plantations, whatever the human cost. As one wit remarked, ‘Were beef steaks and apple pies ready dressed to grow on trees, they would be cut down for cane plants.’

18

But in the words of the eminent food historian Elizabeth Abbott, ‘So many tears were shed for sugar that by rights it ought to have lost its sweetness.’

19

Sugar was indubitably the main engine driving the European slave trade. England was not the first country to trade in human flesh, but due to its maritime power it became the dominant transatlantic transporter of enslaved Africans. It has been estimated that British ships transported between three and four million Africans to the Americas. The Caribbean islands became the hub of the British Empire, the most valuable of all its colonies. By the end of the eighteenth century, £4 million-worth of imported sugar came into Britain each year from its West Indian plantations.

20

Britain was growing rich on the white stuff. Its impact was epic and irreversible.

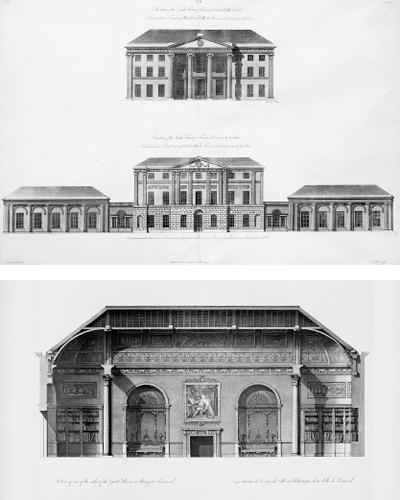

Elevations of the north and south fronts of Kenwood House, and the interior of Lord Mansfield’s Library, by Robert and James Adam

William Murray was born on 2 March 1705, at Scone Abbey in Perthshire, Scotland. He was the fourth son of the fifth Viscount of Stormont and his wife Margaret, and one of fourteen children. Though he was born to Scottish nobility, it was an impoverished line, and he was forced to make his way in the world by his intelligence and hard work. He attended Perth Grammar School, where he mixed with boys from different social backgrounds and studied English grammar and style as well as Latin. This gave him an edge: his legal writings were always supremely stylish, unlike those of some of his peers educated south of the border, who were schooled exclusively in the classics. When he was eight his parents moved away, and left him and his younger brother Charles in the care of his headmaster.

1

In 1715, when William was in his tenth year, the recently formed political union between Scotland and England was shaken by the first ‘Jacobite’ rising, otherwise known as the ‘Fifteen’. This was an attempt, led from Scotland, to overthrow the newly installed Hanoverian King George I and restore the Stuart monarchical line that had come to an ignominious end with the deposition of King James II in 1688. Perceived to be returning the country to Catholicism, James was deposed and exiled when a group of powerful Protestant aristocrats invited William of Orange to come to England with an army. The Dutch invasion came to be known by Parliament as the ‘Glorious Revolution’; among its consequences were a strengthening of Protestantism, Whig supremacy and a limitation of royal powers. The Jacobites took their name from the Latinised form of ‘James’, and their ambition was to bring back ‘the king over the water’, James II’s eldest son, James Francis Edward Stuart, who became known as ‘the Old Pretender’. His son, ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’ or ‘the Young Pretender’, would lead another, more substantial, Jacobite rising thirty years later, in 1745. Both would end in military defeat. Scottish nationalistic resentment over the union and English suspicion of Jacobite tendencies were unavoidable contexts for the lives of families such as the Murrays, which had to make a choice between Scotland and England, Edinburgh and London.