Below Mercury (8 page)

‘Right. Introductions. I guess you’ve already met by now, but for the record, this is Captain Foster, who will be your mission commander, and First Lieutenant Wilson, who will be the copilot and second in command. Captain Foster will be in charge at all times when you are on board. Her first duty is to ensure your safe return, and she has

absolute

command on board.’ Helligan’s gaze swept over Abrams, Elliott, Bergman and Matt in turn, emphasising his point.

‘Now, you gentlemen will be passengers on the voyage, but each of you will have daily work duties to perform. Captain Foster will assign your duties while on board, and you will complete these to the best of your ability, or forfeit certain privileges. You’re going to be in space for over three months, and it’s essential that discipline is maintained. The mission commander has legal powers to remove privileges, restrain, or even sedate you, if in her view any of you become a hazard to the ship or to the success of the mission. Your space pay allowances from your employers will be paid through the Astronautics Corps, and I remind you that we have powers to make deductions from this pay for any breaches of discipline.

‘There’s no turning round once you’re in the transfer orbit; the only way back here is by going to Mercury and returning, so it’s no good having second thoughts once you’re on your way.’

Matt had heard this sort of blunt warning before. There had never been an actual mutiny on a spaceflight before, but it had come close on more than one occasion. Long flight times, and the boredom and isolation of deep space, could cause apparently trivial issues to blow up out of all proportion. There were many similarities with the long ocean voyages of past centuries, and the captain’s word literally had to be law.

‘Mr Abrams, as the representative of the SAIB, is in overall charge of the mission once you are safely delivered to Mercury and your equipment offloaded. The initial mine entry will be led by Mr Bergman, representing the Space Mines Inspectorate, and once he has conducted a thorough safety assessment, Mr Abrams will take over and lead the investigation to a conclusion.

‘In a change to your briefing notes, Mr Bergman is now also representing the interests of the Space Graves Commission. As you will be entering a designated space grave, there are some formalities and procedures that need to be observed while you are in the mine, as well as the exit and sealing procedures.’

Helligan continued to cover the roles of each member of the mission team. He left Matt until last, ensuring that Matt was in no doubt as to where he came in the perceived order of importance.

An hour later, in the first break of the day, Matt found himself facing Clare, who had come up to speak to him.

‘You’ve been to Mercury – to Erebus Mine – several times before.’ She made it sound faintly like an accusation.

‘Yes. I did three trips over about six years, including the last one just before the accident.’ He sipped his coffee.

‘What do you remember of the approach and landing? I’ve studied the charts, and I’ll be starting landings in the simulator next week, but it would help to know what it’s like from someone who’s been there.’

‘Oh, sure.’ Matt gathered his thoughts, and tried to remember. ‘Well, you can’t usually see much from the crew shuttles, but there was one time I was sitting right behind the copilot, and I had a pretty good view. The Sun was lighting up all the craters from the side as we got closer. It looked very dramatic, kind of scary.

‘Meng-fu crater itself is massive, it dominates the horizon as you approach, and when you go down into it, well – it’s just one huge black pit; you can’t see anything inside it. It feels like you’re just falling down into nothingness. When you’re deep down inside the crater, and you get used to the darkness, you can see the mine and the refinery lights from some way off, and then as you get closer you can see the landing pad itself – it was floodlit then, but of course it won’t be for us.’

Clare nodded, and took a drink of her coffee, but Matt sensed he hadn’t told her anything she didn’t know already.

‘So, why do you want to go back?’ she asked suddenly.

Matt was surprised by the directness of her question, and his mouth fell open slightly.

‘I – represent the relatives class action group, and—’

‘I know what you’re there to do,’ she interrupted, ‘but the relatives would never have proposed you as their representative if you hadn’t

wanted

to go back.’

Matt wondered if he wanted to tell her. The directness of this serious young woman was disconcerting.

What the hell. They had to spent months cooped up together anyway.

‘Well, the accident left me feeling – like I’d escaped, and they hadn’t. I wasn’t any better than any of them, it could have been me in the mine. Going back makes me feel like I’m somehow making – amends for things.’

Matt paused. It had been a long time since anyone had asked him how he felt about anything. His throat had gone dry, and the last words had been difficult to get out. He took another drink of his coffee.

Clare stared back at him for several seconds before replying, but her gaze had softened.

‘So. You feel guilty for surviving. It’s not unusual. But there must be other ways of coping than by going back. Haven’t you been offered any counselling?’

Matt looked down, and he hesitated, wondering if he should tell her.

‘Yes – I had several sessions in the early days after the accident,’ he said at last, ‘but it didn’t really help, and I stropped going after a while. I felt such a fake – I was one of the survivors, after all.’

‘It doesn’t mean you don’t deserve a bit of help.’

‘Maybe. But none of the counselling seemed to work. I guess that’s why I got involved with the relatives, and the class action – I felt like I was helping people who really needed it.’

Clare waited, listening.

‘I just need to know what happened. I keep seeing it – the accident – imagining what it was like for them. It’s worse than not knowing. I’ve got to go back and see it with my own eyes. I’ve got to know how they died.’

Helligan stood at the front of the room as they finished their break, flanked by a thin, sandy-haired man in civilian clothes. Matt recognised him from earlier briefings as Rawlings, the mission planner.

Rawlings was one of the civilian specialists retained by the Corps for their expertise in crucial areas. He had a hurried manner that gave the impression of him never having enough time, and the pale complexion of someone who spent too much of his time away from the Sun, in darkened control rooms in the bowels of FSAA facilities. He seemed nervous and ill at ease as Helligan introduced him to the team, and as Helligan went to sit at the back of the room, Rawlings dimmed the lights at once, as if he felt safer in the familiar darkness.

A view of the Inner Solar System appeared on the viewscreen wall behind Rawlings, silhouetting his head and shoulders.

At the centre of the display, a tiny Sun burned, and the planets circled round it like glittering marbles in space, following the coloured ellipses of their orbits as they moved round in accelerated time.

The display zoomed in on the three innermost planets. The blue globe of the Earth moved slowly at the edge of the screen, Venus a little faster, following the yellow circle of its closer orbit, and finally Mercury, pursuing its highly eccentric orbit close to the Sun.

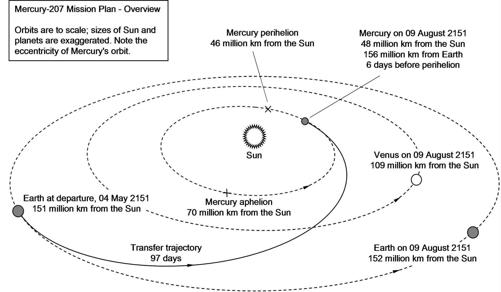

‘This is the situation of the planets right now,’ the silhouette of Rawlings said, freezing the display. ‘The launch window we’re recommending is here—’ he fast forwarded the display a few months ‘—in the early hours of May fourth. Transfer orbit insertion at zero six thirty UTC will put you onto a minimum-energy trajectory to Mercury, with a journey time of just over ninety-seven days.’

The display moved forward again, and a thin green line sprouted from Earth and curved inward, converging on Mercury. The mission planner stopped the display as the green line touched the innermost planet.

‘Your rendezvous with Mercury is on August ninth, six days before Mercury’s closest approach to the Sun. The orbit insertion manoeuvre takes you over the North Pole, and into a standard polar orbit.’

Rawlings zoomed in closer on the display, and the tiny dot of Mercury expanded until it became a grey globe. A graphic of a space tug appeared at the end of the green line, moving against the background of the stars. The mission team watched as the tug fired its engine, slowing down and moving into a circular orbit around Mercury.

Clare leaned forward. The tiny aircraft-shape attached to the front of the tug occupied her full attention.

‘Just a moment,’ she said.

Rawlings halted the animation.

‘What kind of ship are we going down to the surface in?’ She pointed at the screen.

‘You’re going to be flying one of the Martian spaceplanes – most likely a modified Olympus two-forty,’ Rawlings said quickly, glancing towards the back of the room. ‘We had one back from Mars last month that needed a major overhaul. We’ve bumped it up the priority list, and it’ll be refitted for the mission.’

‘You’ve got to be kidding.’ Clare shook her head in disbelief. ‘Why are we taking a

spaceplane

down to Mercury? Why can’t we use one of the crew shuttles?’

‘Because we don’t know what state the landing pad is in after the refinery explosion,’ Helligan’s drawl cut in from behind her. ‘If the pad’s been put out of action by the explosion, a shuttlecraft won’t be able to land.’

Clare started to speak, but Helligan waved a hand dismissively, and continued: ‘Look, shuttlecraft are designed for landing on flat, concrete pads; they’re not able to land on crater floors. And they don’t have the radiation shielding for an extended stay on the surface. Those spaceplanes are built to operate off dirt strips on Mars – they can take hard landings on rough terrain, and they’ve got plenty of shielding. It’s a safer option.’

Clare subsided for the moment. Helligan had a point. If they had to land on the uneven terrain of a crater floor, she would rather be in the spaceplane. Still, it was a big, heavy craft to haul all the way to Mercury.

‘What about living space when we’re on the surface? We might be there for some time,’ she asked.

‘Inflatable Mars habitat modules, carried in the spaceplane’s cargo bay,’ Rawlings answered. ‘The spaceplane can supply all the power and air you need to run them while you’re there. The habitats have adequate radiation shielding for your stay, but you’ll have to retreat into the spaceplane if there’s a major solar event. In the most extreme cases, you may need to take shelter in the mine itself.’

Clare nodded as she made a note in her pad. They seemed to have thought it all out.

Rawlings was looking at her, as if waiting to see if she had more objections. She nodded for him to continue.

Rawlings turned back to the display behind him, and restarted the animation from where the space tug entered orbit round Mercury.

‘Your orbit takes you directly over the South Pole, every ninety-six minutes,’ he continued. ‘Now, for the landing, you’ve got to make a special manoeuvre.’

The animation showed the spaceplane undocking from the tug, and nosing round to latch onto a large, torpedo-like fuel tank, before starting its descent.

‘This drop tank provides the spaceplane with extra fuel for the mission, as there will be no refuelling facilities on the surface. The drop tank is jettisoned shortly after the de-orbit burn.’

On the display, the empty tank fell away from the spaceplane. The display zoomed in further, following the craft as it fell out of the black sky toward the spreading landscape below.

‘Even with this extra fuel, making a descent to the surface and returning to orbit again is right on the limits for the mission. There is very little margin for error. You will be carrying a heavy load of fuel and equipment, which will limit your hover time over the surface before you have to commit to a landing. We have tried to maximise—’

‘Look, just cut to the bad news. How much hovering time do we have?’ Clare’s voice interrupted.

The mission planner stopped, and he glanced at the back of the room first, before answering Clare’s question.

‘It’s going to be – sub-optimal. We calculate that with your fuel margins, and projected allowances for error, you’re looking at a little over – ah, ninety seconds.’