Beneath the Sands of Egypt (30 page)

Read Beneath the Sands of Egypt Online

Authors: PhD Donald P. Ryan

The powerful surge was not kind to any of the tomb's four chambers. The ceramic contents of Chamber C, for one, were violently slammed against the floors and walls and buried deeply in the muck during the first of what would be many flood events to damage the tomb. Whatever else that might have been in this room

suffered a similar fate. Anything organic had scant chance of long-term preservation. The skeletal torso we had previously uncovered represented a mummy whose wrappings had likely rotted away quickly. Like the pottery, it, too, had been slammed against the wall, probably losing its head in the process. We found very little of the rest of it, other than a few small skull fragments, and we even entertained the notion that perhaps the mummy had washed in from another chamber in the tomb.

The pottery provided us with an Eighteenth Dynasty date, but unfortunately no names or any other sort of writing was attached to them. The tedious removal of the debris from Chamber C continued, and one day a nice surprise was discovered: a fragment of a limestone canopic jar with two lines of inscriptions. I was off working on a television program, and Denis could hardly wait to report the news. This is exactly the sort of information we had hoped for that might tie the tomb to actual individuals who lived and died in Egypt around thirty-four hundred years ago. That night Denis brought the images up on a laptop computer, and I could see the clearly cut hieroglyphs, but excitement soon turned to disappointment. There were two lines of inscriptions, all right, with a funerary inscription. Such inscriptions, though, often contain four lines, ending with the name of the deceased, and the essential part was missing from our fragment. So close, I thought, but so typical of our experience working in these undecorated tombs, as they don't give up their secrets easily.

Lucky for us, it would be only a few days until an adjoining piece of the canopic jar was recoveredâwith the missing two lines of text! And yes, there was a name, that of “the god's father, Userhet.” “God's father” was probably an interesting job in the New Kingdom. Although it sounds as if it could be applied to the father of a pharaoh, it actually seems to be a kind of priestly title for one

with specific religious duties. The name Userhet is certainly known for several high-ranking individuals of the Eighteenth Dynasty, but there was something oddly familiar, if not suspicious, about this particular combination of name and title.

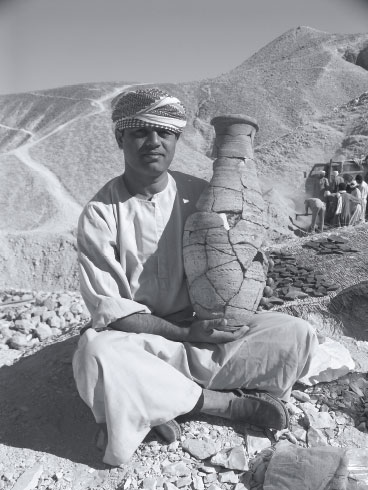

Pottery restorer Mohammed Farouk holds a reconstructed pot from KV 27, the result of weeks of work sorting through innumerable fragments.

Denis Whitfill/PLU Valley of the Kings Project

I checked some images on my computer. Yes, I knew this Userhet. His name and title were found on the three canopic jars that Howard Carter had excavated in the ruins of KV 45, just around the corner from Tomb 27! We had found pieces of the fourth jar! Rather than finally having achieved the satisfaction of matching tomb to owner, we were instead met with a puzzle. Obviously, the jars belonged together, and something was clearly amiss. Was KV 45 indeed the original burial place of Userhet, with one of his jars taken elsewhere by tomb robbers or others? Could KV 27 actually be Userhet's original tomb? Given a score of three to one, KV 45 versus KV 27, one might assume by sheer numbers that 45 wins. Perhaps, but the simplest explanations are not always the most accurate. Could the canopic jars have been washed from elsewhere into one or both tombs by the floodwaters that devastated each of their original burials? Maybe, but it seems far-fetched. Nonetheless, I prefer the explanation that the jar fragments in KV 27 are intrusive, and thus we are left where we were before, searching for answers that continue to elude us.

Meanwhile our study of the artifacts from all six tombs in our concession continued. When we again reopened KV 60 to retrieve a few objects, we were met by a surprise: The wooden box holding the female mummy was gone, and so was the mummy. She had recently been taken to Cairo for study by Zahi Hawass and his team of experts. The questions concerning the death of Hatshepsut and the whereabouts of her mummy were still unanswered over fifteen years after the press had announced that I had in fact rediscovered her mummy. I maintained my position that the KV 60 mummy appeared royal to me, and I suppose Hatshepsut could be a candidate for its identity, but we had no way of telling.

Zahi must have been thinking about Hatshepsut for some time, and identifying her mummy would be a worthwhile project

that he was certainly capable of organizing. He was well aware of the mummy in KV 60 and was apparently very impressed when he first laid eyes upon her. She would certainly need to be included in any serious study.

The author holds a fragment of an inscribed canopic jar from KV 27 belonging to Userhet.

Denis Whitfill/PLU Valley of the Kings Project

At the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, Hawass gathered together four unidentified female mummies, each of whom he believed had circumstantial reasons to be included in a short list of contenders who could possibly be the female pharaoh. Among them were the two mummies originally noted by Howard Carter in Tomb 60: the nurse named Sitre, still in her coffin that had been removed to Cairo around 1906, and the mummy we encountered when we rediscovered the tomb.

The mummies were CT scanned in search of evidence that could provide any sorts of clues. The possibility of making a solid identification was slim, but it was at least worth a try. Along with the mummies, a few surviving objects related to Hatshepsut's burial were brought out for examination, including a small wooden box bearing the pharaoh's name. It had been found over a century before in the famous Deir el-Bahri mummy cache and had been used like a canopic jar, containing a mummified liver, presumably that of Hatshepsut herself. When the box was scanned, it was found to contain something else, something unprecedented. It was a tooth, and it must have been put into the mix during the mummification process. If it had fallen out during embalming, I can't imagine that such an integral part of a pharaoh would be merely thrown away. So here apparently was Hatshepsut's tooth, a revelation with profound implications. In reviewing the CT scans, it was found that there was one mummy missing the appropriate tooth, and, like Cinderella's slipper, the tooth exactly matched the mummy I'd rediscovered from the floor of KV 60. It was the sort of rare discovery that will likely happen only once.

In June 2007, Zahi announced the news that the mummy of Hatshepsut had been identified, and it was a media sensation. My phone rang constantly for days, with reporters from all over the world asking my opinion about the discovery. As I wasn't directly involved in the project, there was not much I could say, other than

that from what I knew, the identification was very compelling, if not completely persuasive, and I continue to believe that. A new state-of-the-art DNA laboratory exclusively for the examination of mummies has been set up in the basement of the Egyptian Museum, and Zahi hopes to bolster Hatshepsut's identity by comparing genetic materials from the mummy with those of her relatives.

Along with the identification, the CT scans revealed some fascinating information about Hatshepsut's death. Some Egyptologists had suggested the possibility that she could have been murdered by her stepson and the rightful heir to the throne, Thutmose III. However, murder would have been unnecessary. Hatshepsut's state of health was a disaster. She was extremely obese and had serious dental issues and cancer, all three of which might have caused or contributed to her demise.

I've often been asked how I felt about my role in all this. Howard Carter originally discovered a tomb, I rediscovered it, and Zahi Hawass identified the mummy. In some ways I'm cynically happy that Carter showed such disinterest in KV 60 that he walked away from it, unintentionally leaving for me the excitement of its rediscovery many decades later. Elizabeth Thomas's speculation about the tomb and Hatshepsut inspired us to consider certain possibilities, and Zahi's interest and ingenuity have apparently solved for us what had long been a genuine mystery.

With our enthusiasm bolstered by the recent news, we returned to Egypt again in the fall of 2007. There was a lot of unfinished business: Two chambers remained to be cleared in KV 27, and our catalog of all objects from the six tombs needed to be reviewed for accuracy and completeness. Much of my team returned, as did Brian Holmes. Paul Buck wasn't able to join us, but we gained an enthusiastic helper in the form of Lisa Vlieg, a recent graduate in classics and anthropology from Pacific Lutheran University. It was

her first trip to Egypt, and we saw to it that she immediately ventured to the Giza pyramids and the Egyptian Museum.

It would prove to be another great field season. One day, for example, Denis was involved in photographing all the artifacts from KV 60, and one of the larger objects from the tomb was set up on his table. It was a sizable piece of curved wood from the head end of a coffin. Most of its surface was covered with a black, resinous substance that had been applied in ancient times. We could even see the brush marks. There are many known coffins from the Eighteenth Dynasty, along with a number of other funerary items that are coated with this black stuff, and the explanations for it are varied. One idea argues that the coating is related to a transition to the netherworld, and another suggests that whatever decoration might lie beneath was not intended to be seen by the living. Regardless of the how and why, the black substance was there.

While the coffin fragment rested on the photography table, our inspector, Abu Hagag, with his usual healthy curiosity, studied its surface carefully. “Dr. Ryan,” he called, “I think I see something hereâ¦a hieroglyph under the surface!” I took a look, and sure enough, in a tiny spot where the resin had chipped away, there appeared to be a hieroglyph depicting a human arm. Perhaps there might also be an interesting inscription beneath, but how to reveal it?

Abu Hagag suggested we request a local conservator, and in a couple of days a bearded, robed gentleman by the name of Sayeed arrived. After a brief look, he quietly commented that he felt he could deal with the situation, and he returned the next day with a small box of equipment. Laying the coffin piece on a woven grass mat, he wrapped cotton around a scalpel, dipped it into an acetone solution, and carefully applied it to the wooden surface. The black substance turned to goo, clinging to the cotton, and our suspicions were immediately confirmed. There were indeed hieroglyphs underneath.

Our excitement mounted as Sayeed worked with amazing patience and caution, even refusing to take breaks. He seemed at least as interested in what was being revealed as we were, and we couldn't help but check back on him regularly. What was eventually revealed astounded us. Beneath the black coating was a beautiful painting of the protective goddess Nephthys, standing on a multicolored basket with her arms raised. Surrounding her were funerary texts bearing a name and a title. The name belonged to that of a chantress, that is, a temple singer, and her name was Ti. Who was this Ti? We had never heard of her, but, more interesting, what were the smashed remains of her coffin doing in Tomb 60?