Big Sex Little Death: A Memoir (19 page)

Read Big Sex Little Death: A Memoir Online

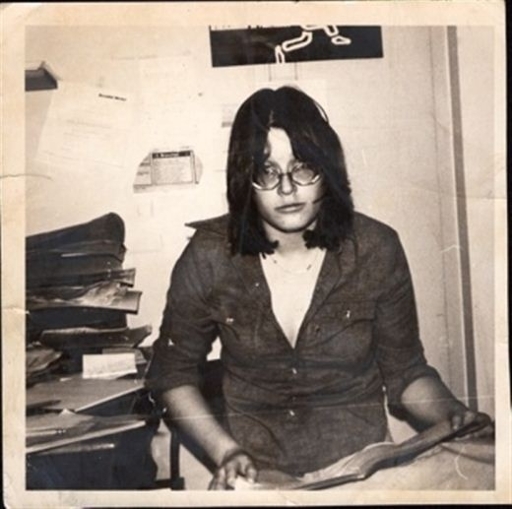

Authors: Susie Bright

He took my hands in his again and raised them to his lips, kissing them. He slumped to the floor, to his knees, but didn’t let go of me — my god, was he having a heart attack?

“I want to ask you,” he said, haltingly, “I want to ask you … to marry me.”

“What?” I jumped up, snatched my hands out of his, and banged my head against the luggage racks. “You don’t need to marry me; you need a lawyer to keep you out of the brig! I can help you, but you don’t even know me!”

He scrambled back up onto his seat and opened his palms to me, as if to show me a stigmata. “When we get to Amarillo,” he said, “I will buy you a ring, and we can get married. I will get you any ring you want.”

Really? How? By robbing a bank? I hadn’t been planning to explain my trip to anyone on this bus. And maybe laying it out for a crazy AWOL G.I. was the worst way to start. But I thought if I could get him to see how different I was from what he imagined, I could help him out of this mess. God knows what had happened to him at Fort Fuckhead or wherever he’d run from. He needed reality and a warm therapist.

“Beau, you and I haven’t talked long, but you should know I’m not getting married to anyone,” I said, shaking my head. “I’m going to Detroit because I’m a socialist organizer, and we’re having a big summer camp to learn how plan our little revolution better — I’ve been planning on going to this since tenth grade.”

“You can go later, after we get married,” he said, reaching out and cupping my breast in his hand. Just cupping it, not squeezing or anything. The action was like a Valium for him — the furrows in his brow disappeared.

I had to admit, he didn’t flinch about “socialist summer camp.” It was like he hadn’t heard me at all.

I looked at my watch. An hour more until Amarillo. Maybe we could just sit there with him holding my breast and he’d fall asleep and I could ring the bell or whatever and get the hell off this bus.

“I’ll read some more, okay?” I asked. He rested his head on my shoulder and kept that one hand of his in the same spot. Some Blue-Haired Beehive lady came back to go the bathroom and shot us a look like she was going to puke.

Well, be my guest.

“Ama-rillah!” the driver called, gliding us over a bump.

I shook Beau-Jesus awake. “Sweetie,” I said to him, “I gotta go to the ladies’ room real bad, and then we’ll go shopping for my ring, okay; meet me right in front of the ticket counter in five minutes?”

I jumped up ahead of him, before he could even stand up, and barreled down the aisle in front of every aged and disabled passenger, barely catching Beau’s cry, “I love you, baby wife of mine!”

The driver waited for each rider at the bottom of the bus steps. I grabbed his arm and dragged him around to the front grille, where the passengers couldn’t see us. “You’ve got to help me — there’s a crazy man back there who won’t leave me alone. I’m going to hide behind the driver’s side back here and when he

gets off you make sure he walks toward the ticket counter — and then I am getting right back on this bus and hiding under someone’s suitcase. Do you hear me?”

He pried my hand off his arm, but he didn’t look confused. “I told you to watch out for the smokers,” he said. He walked back to the front to help a few more old ladies with canes down from the bus.

I crouched down behind the giant front tire on the driver’s side. I could see everyone’s shoes walking away from the bus. Beau-Jesus was the very last pair of boots. I could see

him pause as the driver pointed him toward the station’s ladies’ room and the ticket counter. He loped away. What a beautiful creature he was. The driver knocked three times on the steel of the outside door, and I scampered back on board, mouthing, “Thank you.” I collected all my shit from the back seat and hid in the Tropical Jasmine bathroom for twenty minutes. When I came out, we were well on our way to Oklahoma City. I looked like a squished sandwich, and I fell asleep for three hundred miles in aisle seat 2B.

The Aorta

W

hen I met kids my own age in Detroit — and I met hundreds, selling

The Red Tide

in front of every public high school in the unified school district — I’d tell them, “I just dropped out of school and moved out here from California.”

Their mouths dropped. “You’ve got it all backward!” they’d say. “Are you crazy?” I had their attention.

“You have something here,” I said, “that you will never find in Los Angeles, even if you looked for a million years. Everything is illusion there.”

Detroit was the opposite of L.A. However bruised the city was in 1975, it was still based on making things that made America run. If Chicago had big shoulders, Detroit had steel quads. You pushed the pedal to the metal. You meant what you said, and you said what you meant.

When I walked into the IS national offices on Woodward Avenue, across the street from Henry Ford’s original shuttered factory, it was a classic case of butt-ugly on the outside and beautiful under the skin. The brick edifice of Ford’s plant was abandoned, weeds growing over barbwire fences. This was the place that built the first car my grandpa owned, the first time he didn’t drive a mule train.

I expected Commie Camp would be a great party in the woods, but it would have to compete socially with any weekend night on Livernois and Six Mile. I lived in a brick house in the neighborhood with five other comrades, presided over by a house dad and house mom named Sam and Sheila. They refused my rent money offerings; Sam set me up in a couch that looked like the same model I grew up sleeping on. Sheila made spaghetti carbonara every Thursday night.

Living in a mostly black city meant that, for the first time in my life, there was no racial tension. None. I’d walk down the street and everyone assumed I’d been adopted into an African American family. A biracial family. And I had, in the same fashion of everyone who’d stuck close to old Detroit. Everyone who lived in the town limits was a worker or unemployed; everyone in management had immigrated far out to the suburbs. The segregation took its toll, but the class consciousness was fierce. Of course, the labor unions were corrupt — but people remembered what their grandparen

ts, black and white, had died for. I didn’t have to explain the same things I’d had to explain standing in front of a supermarket on Santa Mo

nica Boulevard, trying to convince a real estate broker’s husband why people who work should have a stake in what they produce.

Detroit families didn’t split apart and move every season like Malibu sandpipers. When I met someone new, I’d meet all their cousins, too. The first barbeque we had in Sheila’s backyard, there must’ve been a hundred people there — but Steve P., who’d moved to Detroit from Tacoma, told me, “It’s really just three families.”

We danced every single night until we dropped. Until the pressure dropped. You didn’t go over to someone’s house in Detroit without dancing.

Legal drinking age was eighteen in 1975, which meant you could get a pass if you were seventeen. My first week in town, my comrades took me to the Aorta, a popular bar down on Six Mile Avenue. I danced with eve

ry man, woman, and dog. Who cared that summertime in Detroit was humid, gray, and smelly? Cold beer never tasted so good.

I remember this bar girl, Pepsi, who showed me her moves. She did a slow grind, never taking her eyes off mine. Her feet held fast to the floor as her hips pushed against the beat. Her hands and arms clasped together like she was holding a hammer — bringing it down, slicing it up. A Bunny with a weapon. I took my pen out of my shirt pocket to scribble on a bar napkin: “Dear Tracey Baby: Forget L.A.! Ship me my records and everything!” I drew hearts all around the border. I had to remember to mail this.

Pepsi grabbed me by my waist off the barstool: “What’re you writing, Susie Hollywood?” Those saber-wielding hands of hers were as soft as a puppy’s.

I slid off the chair and abandoned my wet postcard.

Commie Camp

C

hili liked to say his Ford Econoline was “infallible.” I loved him, but Chili liked to say everything was the opposite of what it really was — that was his humor. He’d coaxed his “baby” all the way out to Detroit from Oakland, and he had the empty Pennzoil cans to prove it.

When Temma told me we were getting a ride back to town from Chili, in his “infallible Ford van,” she didn’t understand why I sunk my head in my camp pillow.

We were sixty miles outside of Detroit, and I was looking forward to heading home after a week of old-school Bolshevik history lessons, sing-alongs, and labor organizing tips. I’d been cooking for two-hundred-plus every night. It’d been a blast, but I wanted to fall onto my couch at Sheila’s and go to sleep for a week.

“What’s your problem?” Temma asked, swatting my bottom. “Chili’s leaving camp tomorrow; it’s perfect. It’s only an hour and a half away.” She tucked her long hair behind her ears with their enormous gold hoops.

“Can’t you get us one of your ‘Cadillac friends’ to chauffeur us?” I asked.

Temma screwed up her heart-shaped face. “That’s over,” she said, and then sang, “‘It was just one of those things … One of those bells that now and then rings … ’

“‘But it’s all over now,’” she sang, switching lyrics and going flat. “And we have a very nice ride with Chili, if you and Hank Runninghorse can keep your fists off each other.

Runninghorse was Chili’s best friend from high school — they did everything together. Runningmouth, as he was often called to his face, was as obnoxious as Chili was kind. But they had built an Oakland chapter of

The Red Tide

up from nothing — I had to hand them that.

“Anyone else coming?” I asked, resigning myself.

“Maybe Joe, maybe Steve P., I don’t know. But you have a seat.”

Four hours later, Chili found me in the kitchen, stripping the clean dishes out of the Hobart. “Sue, I’m sorry, the Ford is screwed. The transmission only goes in reverse, and that’s with a lot of pleading.”

I looked around the camp kitchen. We were the only two left. “There’s hardly anyone here,” I said. “Who’s going to take us back to the city?”

Chili said he’d already thought of that. He was a little too enthusiastic — or maybe he was just playing his opposites game.

He told me some autoworker contact, named Earl, also had a Ford van, and he was going to take Hank, Steve P., and me all the way back to the office, door-to-door service. “He lives in Hamtramck!” he added, like that was a plus.

“A new contact, up here?” I was a little startled. The whole point of Commie camp was to better educate yourself so you could be a better recruiter, but you had to be pretty deep into socialism to attend in the first place. It wasn’t for newcomers. I’d heard more obscure Trotskyite history in the past week than I’d hear again in a lifetime. Last night Fat Henry had gotten drunk, peeled off his undershirt so that all his fur stuck out, and started bellowing out some dirty ballad about a Trot named Max Schachtman and a fat girl.

Really, I had been in the IS for a year and a half now, and I was the closest thing to a “newbie” I’d met in camp.

“This guy Earl’s been mostly studying with the UAW caucus in the East Barracks,” Chili said, pointing behind him.

I shrugged and told him I’d be ready in an hour. Like young Scout in To Kill a Mockingbird, if I could’ve taken Chili’s hand right then, with great prescience, I would have said, “And there started the longest night of our lives.”

I wasn’t happy to be the only girl in the car. Temma had disappeared into the night with some new beau from the River Rouge plant who wore a silver spoon around his neck and had a Cadillac just for two.

When we gathered at the parking lot at noon, I started to get in the back of the van, not looking at anyone, ready to read my John Reed memoirs in the back seat. Runninghorse grabbed my forearm and said, “No, Sue, you sit up front.”

It was impossible to think that Hank was being chivalrous. The best seat in the vehicle? What gives? Hank rejected all niceties of male-female etiquette as counterfeminist, and everyone who knew him understood that he’d let a door slam in his grandmother’s puss without a second glance.

I climbed up into the bucket seat, still puzzled, and came face-to-face with Mr. Earl’s big yellow grin, and even yellower hair, hopped up in the driver’s seat.