Big Sex Little Death: A Memoir (22 page)

Read Big Sex Little Death: A Memoir Online

Authors: Susie Bright

The comrades in the South didn’t care what my motives were — they were so demoralized from the racial onslaught down there. Busing had turned Louisville, like South Boston, into a mini-race war. They couldn’t imagine what bureaucratic inferno I was leaving behind. A nice warm gun to cuddle up to at night might just be a tonic.

It was hard for me to keep my moving plans a secret. But I knew I couldn’t just leave “of my own accord” — I’d be treated like a traitor.

The worst was coming right up. I had to stage a little farewell plea; I had to get an audience with Hugh. As he reminded everyone in his bulletins, “The National Secretary must approve all relocations.”

I wasn’t a very good actress — you could see everything on my face. But I was counting on Hugh’s weaknesses, his famous ego, to let me go — because by his definition, I was already damaged goods. He’d sexually appraised and rejected me a good year ago.

How did the IS ever end up with Hugh? He was our very own British pretender to the throne. He was rumored to have run an OTB office in his past life — not to mention a carny, a card player, and a whoremonger. A Brian Clough wannabe. Whatever his résumé, he’d created a Queen of Hearts, atmosphere where everyone was primed for a kangaroo trial or a casting couch.

The previous Sunday night I’d printed ten thousand red, white, and blue flyers for him, with the headline “Justice Means ‘Just Us,’” atop a caricature of a white foreman holding a black employee in a headlock. The illustration had become my own private insignia.

It was odd to make an “appointment” with Hugh. On our first — and last — occasion to speak in private, he’d been the one to make an appointment. He had called round to be wined and dined and fucked. I had still been in L.A., in the middle of my affair with Stan, and had just dropped out of high school.

Hugh was touring all the U.S. branches, and he was dying to see Malibu. Stan got kind of queasy when I told him Hugh had “called” for me, after Temma wasn’t available. But Stan didn’t stop it.

I could tell Hugh considered my assignment — being his date, his chaperone — to be a great honor for me. My curiosity got the better of me. I’d never played geisha before. My lovers were my friends, not men who called long distance with a list of their likes and dislikes.

It all went wrong with Hugh. I took him to Topanga Beach at sunset, and he stared at it like it was nothing but a cold pile of sand. I took him to a spaghetti restaurant that everyone at Uni High thought was fancy, and he pronounced it rotten. I barely had enough money to cover his bar tab.

I hoped that the sex of the evening would save it, but it was not to be. He was barely in my apartment before I accidentally sat on his leather coat and he lost his temper.

“You fucking cunt, you’ve wrinkled it!” he said.

My eyes watered, and he was quiet for a moment.

Then he asked me if I had any early Rod Stewart. What a face-saver. It was a good thing I had a decent record collection, because we both had to concentrate on something while we screwed each other. The needle thankfully didn’t skip. I don’t remember his penis inside me at all. “Maggie May” was a tranquilizer.

Now, a year later in Detroit, I had my second appointment with the great man. In Hugh’s office, that same blond leather jacket of his was hanging on a wooden hanger on the back of his door.

“So what is today, luv?” He put his feet up on the desk, as if we had cozy chats like this all the time. I don’t think that I’d ever been alone with Hugh in his office. No electric mandolin to help us out this time.

“I came to talk to you because things haven’t been working out for me here,” I said. “I’m too old for the high school stuff. I’m eighteen now, and I haven’t been able to get a job in auto or Teamsters —”

“Yeah, it hasn’t been your year, has it?” he interrupted.

I had to get to the point quickly, before he became too interested in running down my character.

“I’d like to move to Louisville. I talked to the comrades there — you know they’re being hammered by the Klan, and they’re desperate for some new blood.”

That was a stupid way to put it. But if Hugh was the butcher I thought he was, he’d appreciate my meat-related metaphor.

For a second he scanned me up and down. I thought his paranoia might prevail. He’d yell, “You’re wearing a wire, you fucking cunt, aren’t you? You’ve come to do me in!”

But I gave him too much credit; I always did. He kicked back off the desk and said, “Yeah, you look like shit. You’ve been useless here. I’ll tell Louisville you’re coming; see what you can do for them.”

This was the point where I was supposed to say, “Thank you, Mr. Fallon,” like a dutiful daughter. I hated him so much.

“You can’t leave until you train Marguerite on the press, though,” he said, saving me from the impossibility of feigning gratitude. He pointed to some camera-ready copy on the corner of his desk.

“We need six thousand of these by” — he checked his gold watch — “five o’clock, so let’s get going, eh?”

He got up to open the door, keys in his hand, ready to lock it behind us. I realized he couldn’t wait for this to be over. Some other lucky cunt must be waiting outside.

I left the office to go downstairs to the party store for a Baby Ruth, and called Sammy and Sheila’s house from the pay phone. I bet they’d be a little sad to

see me go.

“He believed me!” I shouted into the phone. “I just have to scrub a few more floors with my bare hands, and then I can go!”

Sammy laughed like a pleased Santa. I could tell he had a drink his hand. “You did alright; I knew you would. See, this is going to work out.” I could hear Sheila yelling in the background that she was going to kiss me all over.

“Yeah, I’ll come home as soon as I finish these flyers. Tell Michael when you see him that it went through.”

I had to re-ink the mighty AB Dick printing press a half-dozen times. It took forever to print six thousand back-to-back in red ink: No Contract, No Work. I did feel like a traitor now, the ink stains all over my arms, legs, and face. The first time I had ever turned on the machine, six months ago, Chewy had shown me into the press room, hauled out a mountain of goldenrod 8½" x 14", and said, “Turn straw into gold.” That’s how he left me.

Sammy and Sheila couldn’t say enough about Louisville when I got home. They were living vicariously through my imminent escape.

“The handsomest men in this whole organization are in Louisville,” Sheila said with authority. She was so good-looking herself, with her titian hair, you had to take her at her word. “If it wasn’t for Sammy, I’d be on a train myself.”

I’d seen the comrades she was talking about at an anti-apartheid conference the previous March, and it was true. All of the Louisville comrades, women and men, were better-looking than average. Maybe they just slept at night.

I’d been entertained in Louisville one weekend. Jimmy J. and Cary R. had taken me to Churchill Downs, not when the horses were running, but on a slow day, to admire the place.

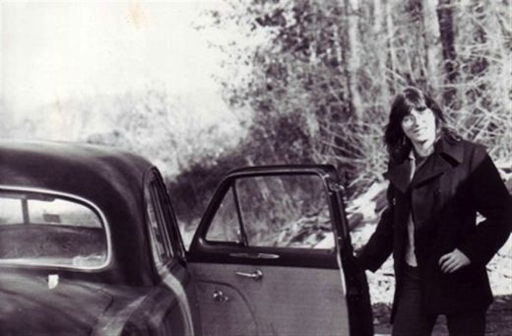

They took me to the Winner’s Circle and put a wreath of roses around my neck. We all posed for a picture, the two of them on either side of me, their arms encircling my waist. Jimmy had been an English teacher before he started driving trucks for Rykoff. Cary was a photojournalist, an old ballplayer from the minor leagues, and he posed me in front of his granddaddy’s Oldsmobile. I never stopped laughing except to put some barbeque in my mouth. It was a beautiful day.

I told Sheila about our day at the races. “See, I told you so!” she said, petting my hair. She was one of the only ones I could talk to about a day off, who wouldn’t look at me like, What do you mean, you fiddled while Detroit burned? She knew I needed a pleasant memory to pack my bags and move somewhere where I really didn’t know anyone at all.

Sheila snuggled with me under her satin quilt, along with a week’s worth of papers she was determined to catch up on. She admitted to me that I was not likely to sleep in a bed of roses every night at my new destination. It might be hard.

Louisville was in the national news all the time in 1975. Sheila read a story aloud from the Times, saying how nine out of ten

white families had pulled their daughters out of high school because they didn’t want them going to school with blacks.

She looked at me, apologetically, and whispered, “The only white people in Louisville defending busing are communists.”

Well, great, I’d fit right in then. I wasn’t nearly as fetching as Sheila, but I had no fear. I was not afraid of anyplace that I could run away to.

The Perfume Counter

M

y first order of business in Louisville was to find a job. I rented a cheap carriage house apartment in St. James Court, where I subsisted on one can of tuna per day.

As before in Detroit, no local comrade could help me find work because they were already known to their employers as “communists” and “nigger-lovers.” I turned in my applications as a complete stranger. My references were two thousand miles away: Would you like to call them?

No one did. My appearance was deceiving.

The first position I found, I discovered in the Courier Journal classifieds. It was for a stock clerk at the largest department store in town, Byck’s. It reminded me of the old I. Magnin’s in San Francisco. They featured a glove counter. Perfume tables filled the foyer with aroma. The most expensive ladies’ garments were on the third level, where I was also interviewed by Miss Dreycall, the store manager.

She gave me a written exam, of a type I hadn’t seen since junior high. It asked the meanings and contexts of words like ancillary and infrequent. There were some arithmetic questions, and a story problem about a squirrel that went to a party. I had to squirm instead of giggle because Miss Dreycall was sitting ten feet away from me.

The test had nothing to do with fashion. I’d hoped she would ask me, “Who is your favorite designer?” or “How do you make a Dior Rose?” As long as it was impossible for me to industrialize, I might as well enjoy my other interests. No one ever asked those kinds of questions in the IS.

Or maybe no one asked because of the way I looked those days — not exactly a Dior Rose. White, but no debutante. I appeared before Miss Dreycall in an acrylic striped sweater and denim skirt; ribbed, pilled tights; and scuffed Mary Janes.

Miss Dreycall had me sit in front of her at a tiny desk with a built-in chair, like a Catholic schoolgirl, while she graded my paper.

“You seem to be quite intelligent,” she said, peering over her glasses. I wished she would tell Hugh that.

“Are you planning to attend college in the future?” That sounded like a trick question.

“Yes, ma’am, but I need to work right now.”

“You will be assisting Miss Love, our couture buyer. She will require your courtesy and attention at all times — she needs a smart girl.”

Miss Love! With special sauce, I hoped.

I was put to work in a back room, filling out inventory cards with a group of five other young women, each of whom lived either with her father or her husband. You didn’t need to know a thing to do this job, except how to count to twenty.

All the girls who lived with their parents were engaged, except Shelley, who was “almost engaged,” and in a panic about her ring. Shannon, the youngest, was engaged at sixteen, and she had been pulled from high school when busing started.

“Well, my father put his foot down!” she explained, as everyone else nodded. Of course. “I don’t know any girls who haven’t left,” she added. More vigorous agreement.

I went to an IS meeting that night and asked Katrina, a local girl, to spell it out for me. “Does that mean that their fathers are afraid they’ll have a black boyfriend or something?”

“That’s not the way they’d put it,” she said. They’d say, “No nigger is going to rape my little girl.”

“Oh, c’mon!”

“I’m serious.”

“So if someone’s dad doesn’t pull his daughter out, that means he wants her to get raped?”

“Yeah, well, it’s end of public schools as far as they’re concerned.”

“But this girl I work with didn’t even get through tenth grade!”

“Neither did you,” Katrina said, and poked me in the side. She had graduated with honors from Oberlin. All these Phi Beta Kappa Teamsters.

“That’s different. I went to Pinko U. instead.”

It was hard to be ringless at Byck’s. I’ve never had so much attention paid to my bare hands. I got asked if I had a boyfriend, and I stuttered. They must have thought I was either frigid or a prostitute. Of course, I was a Yankee, and Yankee girls don’t have anyone looking after them, which is why they are frigid. Whores.

I could not say to them, “I’m having sex with the branch organizer and the head of the Teamster caucus after our meetings — sometimes with the two of them together — but it’s not serious.”

I could not say, “You should really go to the West End clubs sometime and see what it’s like not getting raped and having a ball instead.”

It was funny to me that they thought “not-white” men were so sexually aggressive — paralyzingly attractive. As if they weren’t just men. No, they thought a black guy just looks at a white girl, and her legs fly open. A pulp novel: She screams, but no

words come out. She is caught on the flypaper of his cock; it’s inescapable. She’s ruined afterward, unsatisfied by anything else, unwanted by her own kind.