Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City

Read Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City Online

Authors: Carla L. Peterson

Black Gotham

A Family History

of African Americans

in Nineteenth-Century

New York City

CARLA L. PETERSON

Copyright © 2011 by Carla L. Peterson.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole

or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that

copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright

Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written

permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased

in quantity for educational, business, or

promotional use. For information, please e-mail

[email protected] (U.S. office) or

[email protected] (U.K. office).

Designed by Sonia Shannon.

Set in Caslon type by

Tseng Information Systems, Inc.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Peterson, Carla L., 1944–

Black Gotham: a family history of African Americans in

nineteenth-century New York City / Carla L. Peterson.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN

978-0-300-16255-4 (alk. paper)

1. African Americans—New York (State)—New York—

History—19th century. 2. African Americans—New York

(State)—New York—Social conditions—19th century. 3. African

Americans—New York (State)—New York—Biography.

4. White, Philip, 1823–1891.

5. Guignon, Peter, 1813–1885.

6. Peterson, Carla L., 1944– —Family.

7. New York (N.Y.)—

Biography. 8. New York (N.Y.)—History—19th century. 9. New

York (N.Y.)—Social conditions—19th century. I. Title.

F130.N4p47 2011

305.896′0730747—dc22 2010039306

A catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of

ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Acknowledgments

THIS BOOK WAS LONG IN

the making, but I was fortunate enough to receive help from many different quarters at every step of the way. Historian friends and acquaintances encouraged me throughout the years. Ira Berlin, Jim and Lois Horton, David Waldstreicher, Leslie Harris, David Blight, and Richard Rabinowitz taught me the historian’s craft. Craig Wilder, Graham Hodges, Shane White, Craig Townsend, and Barney Schechter answered every question put to them, large or small. Martha Jones passed on invaluable archival material. Through careful editing, my agent Sam Stoloff showed me how to transform the data I had collected into narrative form.

Archivists went out of their way to help. I owe a special debt of gratitude to staff: at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, especially Diana Lachatanere and Steven Fullwood in the Manuscripts and Rare Books Division, Mary Yearwood and Antony Toussaint in Prints and Photographs, and Christopher Moore, curator and research coordinator; at the New York Public Library Schwartzman Building, especially Matthew Knutzen in the Map Room, Virginia Bartow at the Arents Collection, and librarians in the Local Historical and Genealogical Room; librarians at the New-York Historical Society. I also wish to express thanks to Gwynedd Cannan at the Trinity Church Archives; Wayne Kempton at the St. John the Divine Archives; David Ment at the New York Municipal Archives; Phil Lapsansky at the Library Company of Philadelphia; and Elaine Grublin at the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Generous support from various institutions gave me the opportunity to devote full time to the project. Fellowships from the University of Maryland, the Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers at the New York Public Library, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Gilder Lehrman Institute were invaluable.

Researchers Christine McKay, Robert Swan, Reginald Pitts, Valerie

Idehen, and Jeremy Fain provided important help in identifying and double-checking facts.

Finally, I owe my greatest debt of gratitude to my family: my father and mother, whose memory provided a continued source of inspiration; my sisters Jane and Danna, my husband David, and my daughters Sarah and Julia, whose faith encouraged me to the end.

THR OUGHOUT THE NINE TEENTH CENTURY

, blacks referred to themselves variously as African, colored, colored American, Negro, and black. Statements by men and women during that period, and my own associated comments, follow this usage. Otherwise, I use the terms black, black American, and African American interchangeably in my narrative.

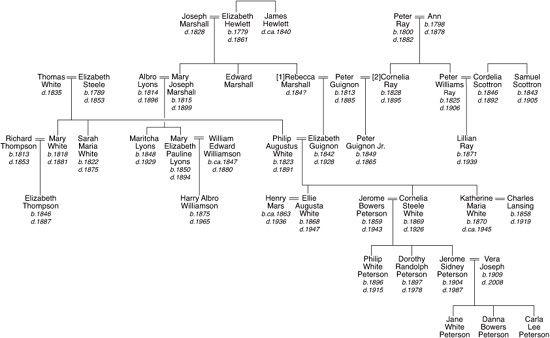

Family tree (Courtesy John Norton)

FAMILY, MEMORY, HISTORY

Denver was seeing it now and feeling it—through Beloved.…

And the more fine points she made, the more detail she provided,

the more Beloved liked it. So she anticipated the questions by giving

blood to the scraps her mother and grandmother told her—and a

heartbeat. … Denver spoke, Beloved listened, and the two did the

best they could to create what really happened, how it really was,

something only Sethe knew because she alone had the mind

for it and the time afterward to shape it.

—Toni Morrison,

Beloved

I ENTERED THE MANUSCRIPT

room of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture with some trepidation. It was brightly lit, uncluttered, and utterly silent. The archivists politely asked me to store my coat and bag in a locker outside the door, and then directed me to a seat facing them at a long, low, bare wooden table. They provided me with paper and pencil and left to retrieve the material I had asked for. Clearly, this was not a place for dilettantes. No chattering allowed, and please refrain from loud exclamations or emotional outbursts.

You’re looking for a needle in a haystack

, my historian friends warned me. But I was determined to find out more about my family’s New York background and write as best I could about “what really happened, how it really was” for black New Yorkers in the nineteenth century.

Like Morrison’s Denver, I had no memories of my own. Beyond that, I couldn’t even rely on scraps I’d been told. All I had was a single

name, that of my paternal great-grandfather Philip Augustus White, and a story about him that eventually proved false: that he was born Philippe Auguste Blanc, a “white Haitian” who fled to Paris at the time of the revolution in Saint-Domingue (Haiti), became a pharmacist, and then emigrated to New York, anglicizing his name to Philip Augustus White.

It made sense to me to begin with a trip to the Schomburg Center, which houses the city’s largest collection of archival material on black New Yorkers, to see what I could find. Going through the manuscript division’s finding aid, I came across a listing for the Rhoda G. Freeman Manuscript and Research Collection. I’d already read Freeman’s book,

The Free Negro in New York City in the Era Before the Civil War.

Although written in the 1970s, it was chock-full of good information, so I decided to take a look at her papers.

The collection consisted of hundreds of note cards and folded pieces of paper stuffed into approximately twelve files the size of shoeboxes. I went through them methodically, taking notes on economic conditions, political rights, community institutions, and the like until I came to a box labeled “biography.” And that’s when I found them: two pages torn from an unidentified scrapbook on which newspaper clippings had been carefully pasted.

The first page was made up of several different items. What caught my eye was the long skinny column on the right containing the obituary of P. A. White clipped from the February 21, 1891, issue of the

New York Age

, the city’s major post–Civil War black newspaper. On the left side, there was an assortment of poems that, judging from the varied print size, had been taken from different sources. On the second page I found a three-column obituary of Peter Guignon cut from the January 31, 1885, issue of the

New York Freeman

, the predecessor of the

Age.

1