Read Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City Online

Authors: Carla L. Peterson

Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City (2 page)

I couldn’t let out a whoop, so I just sat there quietly, my heart racing, and read through Philip White’s obituary line by line, devouring every word.

According to the obituary, White had been born sixty-eight years earlier. Doing a quick calculation, I figured out that the year of his birth must have been 1823. After the untimely death of his father, White was “thrown upon his own resources.” He attended one of New York’s

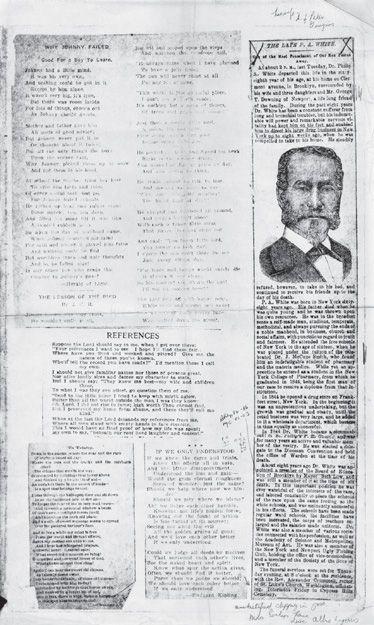

Obituary page for Philip White, with clippings from unidentified newspapers (Rhoda G. Freeman Manuscript and Research Collection, MG 313 Box 7, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library)

African Free Schools until the age of sixteen and then began an apprenticeship in the pharmacy of James McCune Smith, one of the first black doctors in the United States. While still an apprentice, White attended the College of Pharmacy of the City of New York, from which he graduated in 1844, “being the first man of our race to receive a diploma from that institution.” That same year he opened his own drugstore in Lower Manhattan. Initially an unpretentious endeavor, it grew into a large retail business to which White eventually added a successful wholesale department.

The obituary intimated that White was a reserved, perhaps even staid, man. It was this sobriety that made him so successful in business. “He was in the broadest sense a self-made man,” the writer opined: “studious, temperate, methodical, and always pursuing the ends of a noble manhood, in business, church, and social affairs, with punctilious regard to truth and fairness.” Even though it’s blurry, the photograph that accompanies the obituary suggests as much: a long severe face, piercing eyes that stare directly out, a thin aquiline nose, and a tidy goatee over which hovers a full, bushy mustache carefully swept to each side off the chin and cheeks. White’s steady comportment served him equally well in both his church life and his activities outside the black community. A longtime communicant at St. Philip’s Episcopal Church, one of the city’s earliest black parishes, he served for many years as vestryman and then senior warden. Over time, he gained admission to the city’s major professional pharmaceutical societies and became a member of both the Academy of Sciences and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Impressively, in 1883, Mayor Seth Low appointed him to the Brooklyn Board of Education. Occupying the colored seat on the board, White successfully lobbied for the improvement of education for African American children. He held this position until his death in 1891. Alexander Crummell, the most eminent African American Episcopalian clergyman of the nineteenth century, to whom W. E. B. Du Bois devoted an entire chapter in

The Souls of Black Folk

in 1903, officiated at White’s funeral.

Feeling amply rewarded, I idly picked up the second obituary. The name “P. A. White” caught my eye, and once again I became absorbed in reading. The subject of this obituary, Peter Guignon, had a daughter, Elizabeth, who had married Philip White. So Guignon was White’s

father-in-law and my great-great-grandfather! Once again, I suppressed a whoop and studied the obituary closely. Its author was none other than Alexander Crummell. A close friend of Guignon’s since childhood, Crummell offered a poignant portrait of the deceased. Making no reference to Guignon’s father, Crummell noted that his mother had come from the West Indies to New York City, where her only child was born in 1813. As a youngster, Guignon attended the old Mulberry Street School for colored children. He was, Crummell wrote,

the contemporary at that school from about the year 1828 of the most celebrated pupils which ever were enrolled upon its records. His school-mates were George Allen, Thomas Sidney, the two Moores (Isaac and George), the three Reasons (Eliver, Patrick, and Charles L.), Isaiah Degrasse, J. McCune Smith, Henry Highland Garnett, George T. Downing. His standing and character in his school days can be seen that he was the friend and intimate companion of every one of these eminent boys, not only in their boyhood, but afterwards in their manhood and maturity.

I recognized these names, Crummell’s included, as a roll call of prominent northern black leaders, and was astonished to learn that my great-great-grandfather had been their friend.

As a schoolboy, Guignon was, according to Crummell, a paradoxical mix of gravity and hilarity. Even the obituary illustration of Guignon as an older man with his broad face and full head of curly hair suggests a much less severe and reserved man than his son-in-law. In adult life, tragedy tempered without destroying the lighter side of his character. His first wife, a former schoolmate named Miss Marshall (my great-great-grandmother) died early, leaving him with young Elizabeth. Guignon subsequently married Cornelia Ray and, like White, became a pharmacist and respected businessman. But tragedy struck again some years later when his only son, a student at Oberlin College who had not yet reached his seventeenth birthday, was killed in an accident. Guignon’s lasting grief over his son’s death, Crummell wrote, strengthened his religious convictions. Like White, Guignon became an active member

of St. Philip’s and a frequent member of the vestry. He engaged in many acts of charity. When he became ill during the last years of his life, he accepted his suffering with forbearance. Upon his death in 1885, “society,” Crummell averred, “lost a unique and singular character, which it is impossible to replace.”

This book is about Philip White and Peter Guignon. It’s not exactly a family memoir, but neither is it traditional social history. It is a narrative that lies somewhere in between. It records my search to find my father’s New York family; my success in uncovering many documents about these two men but my frustration in discovering only faint traces of other relatives, particularly women; my determined effort to tell their story despite the little I had. Peter Guignon’s and Philip White’s lives shape the contour of my narrative, yet they also serve as a pathway to a larger public history: the history of social movements, political events, and cultural influences in which my great-great-grandfather and great-grandfather were participants and witnesses.

We still hold certain truths about African Americans to be self-evident:

that the phrase “nineteenth-century black Americans” refers to enslaved people; that “New York state before the Civil War” denotes a place of freedom; that “blacks in New York City” designates Harlem; that the “black community” posits a classless and culturally unified society; that a “black elite” did not exist until well into the twentieth century. The lives of Peter Guignon and Philip White belie such assumptions. They were born free at a time when slavery was still legal in New York state. They lived in racially mixed neighborhoods, first in Lower Manhattan and then after the Civil War in Brooklyn, at a time when Harlem was a mere village. They were part of New York’s small but significant black community, and specifically its elite class.

In 1820, the city counted approximately 10,300 black inhabitants, and their numbers never reached above 16,300 until after the Civil War.

2

They were concentrated in the city’s Fifth, Sixth, and Eighth Wards that ran from Bowery Road west to the Hudson River. In the harsh and competitive environment that was New York City, blacks suffered from the additional burden of deep and pervasive racial discrimination. Most remained mired in the ranks of unskilled and illiterate

laborers. But a minority prospered, among whom were my great-great-grandfather, many of the “eminent boys” of his school days, including James McCune Smith, George Downing, Henry Highland Garnet, Charles and Patrick Reason, among others, and, in the next generation, my great-grandfather. They received the best education available to black children at the time. In adulthood, some became tradesmen—carpenters, shoemakers, or tailors—while others gained a foothold in the professions as schoolteachers, ministers, or pharmacists. A number emerged as leaders of the city’s black community; several achieved national prominence. They founded newspapers, literary societies, political associations, and schools. They engaged in political resistance, holding conventions and mass meetings, and lobbying city and state legislators.

Although their tactics often differed, these young men shared similar values and goals. Much like white middle-class Americans, they placed emphasis on education, a Protestant ethic of hard work, and strict adherence to a code of respectability. Like them, they strove for socioeconomic advancement and security. Yet, given their second-class status, they needed to fight for rights that many of their white counterparts already took for granted: the acquisition of citizenship in the country of their birth, the attainment of all the privileges and obligations that came with being an American. They sought, as W. E. B. Du Bois later wrote, “ultimate assimilation

through

self-assertion, and on no other terms.”

Following the example of New York’s reigning literati, members of the black elite proudly referred to the place where they lived as Gotham and themselves as Gothamites.

Theirs was a pre-Harlem world. The early presence of men like Peter Guignon and Philip White in the city overturns the commonly held notion that New York’s black intellectual and cultural life began in Harlem with the New Negro Renaissance of the 1920s. In fact, many of the Harlem Renaissance figures familiar to us were not native New Yorkers but came to the city as young adults from places as close as New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Washington, D.C., and as far away as Jamaica and Guyana. But Peter, Philip, and their friends were New York born and bred. They lived downtown in the midst of the city’s white population,

not in a segregated black neighborhood. They were not bohemians or rebels; to the contrary, they held values remarkably similar to white middle-class norms.

Men like Peter and Philip were, Du Bois admitted, “exceptions.” But he took umbrage with “the blind worshippers of the Average” who “cried out in alarm: ‘These are the exceptions, look here at death, disease and crime—these are the happy rule.’” Du Bois never disputed the existence of the “happy rule,” but he blamed it on a “silly nation” and insisted that the exceptional needed to be nurtured as the “chiefest promise” of the race. I follow his call.

3

So many questions swirled around in my head. How did a black elite emerge in early nineteenth-century New York? What were the educational opportunities for its members? How were they able to enter professions like pharmacy? Which city neighborhoods did they live in and what were their living conditions like? How did they relate to white New Yorkers, and to less privileged blacks for that matter? I was even more bothered by another set of questions. Why have histories of New York City ignored the presence of this nineteenth-century black elite until quite recently? More puzzling still, why did African Americans, my family included, forget this history? Why did they not hold on to their memories of the past, instead believing, as Toni Morrison wrote in the last pages of

Beloved

, that this was “not a story to pass on”? Why did I have to go to the archives to reconstruct my family’s history?

Perplexed, I turned back to the Morrison quote with which I began this chapter and thought about how Denver so desperately wished to give “blood to the scraps her mother and grandmother told her—and a heartbeat,” and how she and Beloved “did the best they could to create what really happened, how it really was, something only Sethe knew because she alone had the mind for it and the time afterward to shape it.”

The need to remember and preserve the past is one of the most powerful of all human impulses, powerful for individuals and groups

alike. In Morrison’s novel, Denver is convinced that knowledge of her mother’s past will help shape her own identity. Not too differently, nations and other communities also hold on to memories of people and events they deem historically significant; these memories lay the groundwork for group identity, inviting each and every member to connect with one another through a shared history and a common set of values. They establish a sense of “who we are as a people.”

Morrison insisted that Denver and Beloved were trying to “create what really happened, how it really was.” This I knew to be impossible. Just as Denver and Beloved possess only “scraps” of Sethe’s life, so communities don’t always have all the facts they need to reconstruct past realities, and sometimes can’t even agree on what those realities are. There’s also the question of whose past is being remembered. Much like Denver and Beloved’s efforts to re-create their mother’s past, societies often seek to hold on to memories of earlier generations that they themselves never experienced. So we need to think of remembering—whether undertaken by individuals or collectivities—as a dynamic process, an act of imagination. Remembering shapes and reshapes the past as it reinterprets this past from the perspective of the present, assesses how it affects the present, and reflects on how it might influence the actions of future generations.

Rituals help preserve memories of the past. Denver and Beloved’s conversation is an example of how family members turn to storytelling to honor past people and events that have shaped the lives of later generations. Nations, too, make use of rituals, setting aside specific days of the year to commemorate past events and reaffirm a sense of group identity. Every July 4, for example, Americans pause to remember the war of independence and the birth of the United States as a nation founded on principles of freedom and equality. Every Thanksgiving they gather together to pay tribute to the hospitality of Native Americans to the newly arrived Pilgrims. Yet national rituals also exclude, failing to take into account the omission of African Americans and other minorities from the “men” honored in the Declaration of Independence as well as the horrific acts of violence perpetrated against Native Americans after the first Thanksgiving. Religions, much like nations, also rely on commemorative

rituals. Every Easter, Christians throughout the world reaffirm the central values of suffering and redemption as they pause to remember Christ’s sacrifice for humankind.