Blacky Blasts Back (8 page)

âHe called us jessies and big girls' blouses. What's that mean?'

âSooks. But don't mind Jimmy. He insults everyone. It's just the way he is. But he

is

tough. Ex

SAS

. Hard as nails. For all that, he's one of the kindest people I've ever known. A top bloke. Now, mate. To quote Jimmy, quit bumpin' yer gums â stop chatting â and help get the barbie ready.'

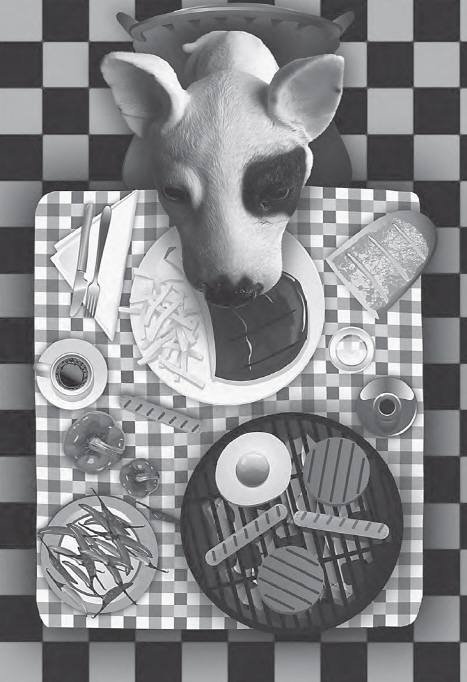

There were snags. There were fat steaks. There were onions. And, for Phil and me, there were vegie burgers. Once the hotplate was sizzling, we slapped on the food and the delicious smell of barbecuing filled the clearing. I was impressed. I didn't know about the other kids in the special boys unit, but I did know Dyl and me. Give us two bits of bread and a slice of cheese and we'd have struggled to make a sandwich. But here we were, getting up a hearty feed for ten.

âMake that eleven, mush,' came a voice in my head.

I paused in my stirring of the fried onions.

âBlacky!' I said silently. âI was worried. Where are you?'

I'd heard nothing from the grumpy hound since early that morning. He'd kept a low profile. It was so cold I was concerned for his safety. It's not like he's got a thick coat. I'd pictured him somewhere out in the bush, half-frozen, half-starving. Huddled under a tree, keeping warm by burrowing under fallen leaves. This was hostile territory. And he's not a big dog. I almost got a tear in my eye thinking about it.

âYou can save your sympathy, bucko,' said Blacky. âI've commandeered one of those empty huts as my headquarters. I'm already planning the next stage of the mission.'

Okay. Forget the huddling under a tree. But it was still freezing, even inside our dormitory.

âYou must be cold, though, Blacky.'

âI also commandeered a sleeping-bag from the stores. Two, actually. Down-filled. The finest the military makes. If anything, mush, I'm

too

warm.'

My concern was dwindling. From the sound of it, he was much more comfortable than me. Then I thought about food. That must be a problem. I mean, it's not as if he was able to bring an esky with him.

âBut you're starving, right?' I asked.

âNot exactly

starving

, tosh. I also commandeered a couple of kilos of dried beef.'

I started to stir the onions again. Here I was, worried about the foul-smelling mutt, and he was living in the lap of luxury. For all I knew, he'd

commandeered

cable

TV

, a heated indoor swimming pool and a laptop with high-speed internet connection. I had visions of a butler bringing him a cooked breakfast and the morning newspaper while someone else gave him a pedicure.

âWell, you can forget sharing

our

food, Blacky,' I said. âBy the sound of it, you're roughing it in five-star conditions.'

âBe fair, mush. I

am

the brains of this operation. And all I'm asking is a bit of warm food.'

I sighed. âAll right, Blacky, I'll see what I can do.'

âWith onions, but no sauce. Make it two snags. Oh, and a steak. Medium rare.'

âAbsolutely, sir,' I said. âCan we interest you in an entree? Wine list? And what about hearing our specials tonight?'

âOi, tosh,' said Blacky in an offended tone. âThere's no need for sarcasm.' There was a pause. âDo you

have

any entrees?'

Dinner was a great success, despite the fact that we burned nearly everything. It wasn't so much meat and vegie burgers as charcoal. But everyone was starving and we ate the lot. I stashed a couple of sausages and a particularly incinerated steak in my jacket pocket. Knowing Blacky, he'd send it back and ask for a refund on his bill.

Stuff him.

After we'd cleared up, we gathered around the camp fire. Although it was freezing, cooking had kept us warm. Now we made a circle around the fire. Phil had brewed a huge billy of tea. Jimmy produced marshmallows and some long skewers. We sat and drank tea and stuffed scorched marshmallows into our faces. It was great. There were only a couple of worries.

One was Mr Crannitch. We hadn't seen him all day, though he'd joined us for dinner. I think he was still sick. From the way he clutched his head, I guess he must have had a headache. He kept sipping from a small metal flask. Painkiller, probably. From time to time he sang a little song to himself. And groaned.

The other worry was John Oakman. He sat opposite me. Whenever I caught his eye, it was clear he wasn't thinking of signing up as the first member of the Marcus Hill fan club. I remembered his ambition of becoming an executioner. John kept looking at my neck. His hands moved as if practising the tying of complicated knots. The marshmallow tasted like ashes in my mouth. Then I realised it

was

ashes. I'd cooked it too long.

âEnjoy it weel ye can,' shouted Jimmy. âAh dinnae ken when youse'll get the like agin.'

Maybe I

was

getting used to him. I understood almost all of that.

âJimmy. Phil,' I said. âDo you guys think the Tassie tiger still exists?'

This was a good opportunity to do research. Blacky knew a lot, but these guys lived here in Tassie. It seemed sensible to tap into local knowledge.

Jimmy gazed at me over the fire. The flames highlighted the crags in his skin and threw the bulges in his head into relief. His face writhed in shadow and light.

âAh'm no the expert oan that,' he bellowed. âPhul's yir man, there, so he is.'

I turned to Phil. He had his head down. Thinking. Finally, he looked up.

âI

know

they're out there, mate,' he said quietly. âI've seen one.'

He told his story. It had happened a couple of years ago. He was hiking alone in the forest, about five kilometres from where we were now. He'd turned a corner of the trail and seen it, not ten metres away. The peculiar stiff-legged walk, the strange way the tail stuck out, the stripes. And then it was gone, a blur into the bush. He saw it for less than five seconds. But there was no doubt in his mind what he had seen. A tiger.

âAye, an' then yir arse fell oaf,' said Jimmy. âIt were a dog, ya dunderheid.'

Phil smiled sadly.

âJimmy's never believed it, but I know what I saw.' He drained the remains of his tea. âAnd it's funny you should mention it, because there's been another sighting recently. Not too far from here. Have you not read about it in the newspapers?'

I shook my head.

âSomeone took a photograph, though it was blurred. What you can see is something that

might

be a Tasmanian tiger. Or, as Jimmy would have it, a dog. But everyone's excited. Amateur tiger hunters have come out of the woodwork. Hordes of the buggers, with fancy cameras and night-vision goggles and motion detectors and whatnot. No scientists. They're convinced the tiger has gone. But the romantics are desperate to prove them wrong.'

âWhat, they're around here?' I asked.

âMate, you can't throw a rock without hitting one. They're camped about ten kilometres away, which is where the photograph was taken.'

Jimmy snorted.

âBuncha mad rocket mental numpties,' he snarled. âAh tell ye, ah hope that critta

is

extinct. 'Cause if them muppets gitta haud of it, it'll be the worse thing that ever happened tae it, so it will.'

I didn't feel qualified to argue with him. Partly because I only understood fifty per cent of what he said.

I was improving. Earlier in the day it had been less than ten per cent.

Mum once said that exercise and fresh air was tiring but gave you a healthy glow. I hadn't listened, mainly because it was

exactly

the thing that old people always said. Like watching television would give you square eyes, carrots helped your eyesight and eating Brussels sprouts was generally a good idea.

But I had never felt so tired in all my life. And it wasn't just because I'd spent a sleepless night manufacturing diced carrots. Judging by the amount I scattered over Bass Strait and John Oakman's face, I should be able to spot a pimple on a mosquito's bum from four kilometres away. My muscles ached and I could barely keep my eyes open. Looking around the camp fire I saw the other kids were feeling the same. Everyone was yawning, faces were glowing and it wasn't even eight-thirty.

It had to be exercise and fresh air. I wasn't going to tell Mum she was right, though. She'd probably use the admission to push her viewpoint on Brussels sprouts.

âTime to hit the sack, guys,' said Phil. âAnd no talking or reading or playing on hand-held game consoles. We're up at sparrow's fart and judging by the look of yous, you all need your beauty sleep.'

We trudged off to the toilet and shower block. All of us except for Kyle, which helped explain the odour of week-old salmon hanging around him in a visible cloud. I hoped someone had brought clothes pegs to put on our noses, otherwise we could all be gassed to death in the middle of the night.

I was first out of the shower. The snags and steak were spreading a grease patch in my jacket pocket. I ducked behind the shower block and called out in my head.

âBlacky? Dinner is served.'

âOn my way, mush,' came the reply.

Actually, he could have saved his mental breath. I knew he was close. And not because me and Blacky had bonded. Not because we were like twins and could sense each other's presence.

It was the smell.

Something evil was headed towards me.

âWhat have you rolled in now, Blacky?' I sighed.

âIt's a beauty, isn't it?' said Blacky. He loomed out of the darkness and sat at my feet. âStroke of luck, that. Stumbled across a mound of horse poo in the bush. No idea why a pony would have been out here in the wilderness, but I'm not one to look a gift horse in the mouth. Or the bum, in this case. The mound was old â nicely crisp on the surface but with a very satisfying soft centre once you'd broken throughâ'

âYeah, okay,' I interrupted. âI'd love to share your all-time-favourite top-ten stinks of the decade, but I'm gagging here.' Sniffing Kyle's armpits would have been heaven in comparison. âHere's your food.'

I put the blackened meat on the ground. Blacky nosed it, then cocked his head and stared at me.

âWhat's this, ya twonk?' he said. âCharcoal briquettes from the barbie?'

âThe meat's slightly overdone,' I admitted.

âSlightly overdone, mush?

Slightly

? It's buggered. It's blacker than a baboon's bumhole and about as appetising. The secret of good cuisine, bucko, isâ'

âLook. Don't eat it, okay. I really don't care. Next time,

you

can do the cooking.

I'll

be the food critic.'

Blacky wolfed the steak. The sausages didn't touch the sides of his throat. I tapped my foot.

âCouldn't have been that bad,' I said.

âIt was,' said Blacky. âIt was worse. I just didn't want any other animal eating it. I have, as you know, tosh, a solemn duty to protect all living things, even at the expense of my own wellbeing.'

I turned to go.

âBe ready, mush,' came the voice in my head. âThe mission starts soon.'

âWhen?'

âIn two days. I have an errand to do tomorrow and I'll be back late. I'll give you and Dylan instructions then. But you are going to have to lose the rest of the people here and come with me into the bush. You might want to start thinking about how to do that.'

Losing eight people? I would have welcomed advice, but Blacky had gone. The smell of horse manure lingered a while longer, but soon that was gone too.

I turned towards the dorm.

John Oakman grabbed me as soon as I came around the corner of the shower block. He shoved my arm up my back and pushed me against a tree. I whipped my head about in desperation, but Dyl was nowhere to be seen.

âPuke on me, eh?' snarled John. âPush me into frozen water, eh? Think you're tough, eh? Think you're hard, eh? Wanna fight, eh?'

âNâno,' I stammered. I was tempted to add âeh' but didn't. âAccidents, John. I . . . I didn't mean to do all that. I'm sorry. I'm really sorry.'