Blacky Blasts Back (3 page)

The thing is, they wouldn't believe me. As far as they're concerned, Rose can do no wrong. If they discovered my sister disembowelling me with a rusty tin opener, they'd assume she was performing emergency lifesaving surgery and double her pocket money.

It's not fair.

So I limped into my bedroom and had a go at my Maths homework.

A man is filling a tank with water at a rate of 30 litres a minute. The tank is 3.5 metres long, 4.5 metres wide and 6 metres deep. However, the tank has a leak exactly halfway up and when the water reaches this level it escapes at a rate of 5 litres a minute. Bearing in mind that 1 cubic metre contains 1000 litres, how long would it take for the tank to overflow?

I thought about it.

â

Never

,' I wrote, â

because only a complete moron with a criminal disregard for water conservation would carry on filling a tank when it was spewing out 5 litres a second through a leak

.'

Satisfied I'd aced that one, I had a shower, brushed my teeth and got into bed. I was going to do some reading, but I was tired out from dinner. It's exhausting having your shins hammered with steel-capped boots. So I turned off the lamp and snuggled down into my doona.

I don't know if this has ever happened to you. You drift into that cosy state of pre-sleep, suspended in warmth. You fall deeper and deeper into a blissful void. Your breathing relaxes into a peaceful rhythm.

And then a cold wet nose is thrust into your ear.

Okay. It must be just me.

I yelled and jumped out of bed in one movement, like one of those vertical take-off military jets. I nearly scraped the ceiling. Just as well I'd only recently been to the bathroom. Otherwise

I'd

have been leaking at the rate of 5 litres a minute.

I pressed back against the wall, peered through the darkness towards my bed and prayed I was in the throes of a nightmare.

âTickle my bum with a feather, tosh,' came a voice in my head. âYou scared the living daylights out of me, you twonk!'

I took a step nearer the bed.

âBlacky?' I breathed.

âWho were you expecting, bucko? Barack Obama?'

I turned on the bedside light.

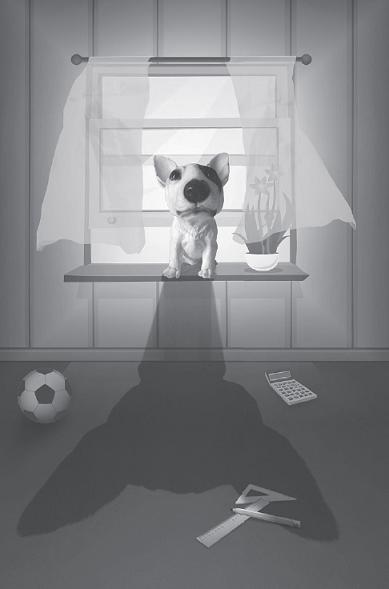

A small, scruffy, dirty-white dog sat on my pillow. It looked at me through pink-rimmed eyes.

âWotcha, mush,' said the dog.

Now this is the bit you'll find hard to believe.

Blacky is a talking dog.

Well, he can't actually

talk

. He's not in demand as an after-dinner speaker, and he'd flunk an English oral outright. But he

can

communicate. Only with me, though.

It works this way. His voice appears in my head and my voice, it seems, appears in his. It's called telepathy: the ability to talk to someone through their thoughts. According to Blacky, I am one of only four people in Australia to have this gift and there aren't many animals who can do what Blacky does. Just thought I'd let you know that while you

could

spend hours talking to a pot-bellied pig, you're unlikely to get anything out of it other than a headache and a reputation for being one snag short of a barbie.

Blacky doesn't turn up often, but when he does it's because he has a mission for me. An animal somewhere needs my help. So far, I've successfully completed two missions. Or rather, me and Dyl have. Dylan is the only other person who knows about Blacky. We are an ecological double-act, tidying up messes that human beings have created. But you'll understand more as the story goes on . . .

âBlacky!' I yelled in my head. âIt's great to see you.'

He cocked his head.

âOf course it is, tosh,' he replied. âYou're only human. Some would say

barely

human.'

I wanted to throw my arms around him, but stopped myself just in time. Blacky doesn't do affection. In fact, he's the grumpiest, meanest, worst-tempered, rudest creature I've ever known. And I've spent my entire life with Rose, remember.

âWhat's the mission, Blacky?' I said.

âWhat makes you think there

is

a mission, tosh?' he replied. âMaybe I'm just passing through and felt like chatting with an old friend.'

âReally?'

âNo. You're not an old friend. You're a brain-dead bozo. Anyway, there's a mission.'

âWhat is it?'

Blacky scratched an ear and gave his bum a quick lick. That reminded me. I knew something was different. Every other time I'd found Blacky in my room he'd been accompanied by a foul smell. You see, Blacky has a fart problem. Well,

he

doesn't consider it a problem, but anything living within a two-kilometre radius does. I've seen flowers wilt, birds plummet from the sky and grown men weep and lose the will to live.

âChanged my diet, tosh,' said Blacky. I'd forgotten there was no such thing as a private thought with him around. âBut, if you're feeling nostalgic, I'm sure I could manage a small one . . .'

â

NO!

' I yelled. âIt's okay, seriously. Tell me about the mission instead.'

âAh, the mission, mush. 'Fraid I can't tell you. That's on a need-to-know basis.'

âWhat do you mean, “a need-to-know basis”? If you've got a mission for me, don't I need to know what it is?'

âOnly those who need to know, know. Those who don't need to know, don't know. You aren't on a need-to-know basis, so you don't know and I don't need to tell you what you don't need to know. You need to know this.'

I let the words roll around in my head for a while, but it was obvious I wasn't going to make any sense of them.

âSo who does need to know, then?' I asked.

âYou don't need to know that. That's also on a need-to-know basis.'

I threw myself on the bed. I'd forgotten how annoying the smelly hound could be.

âSo let me get this right,' I said. âYou've got a mission for me, but I don't need to know what it is? How am I supposed to complete it, then? And if you tell me that's on a need-to-know basis, I should warn you I'm liable to insert my foot up your backside.'

Blacky sniffed inside my head.

âCharming,' he said. âWhy is it that humans resort to violence when they don't get their own way?'

âI can't tell you,' I replied. âThat's on a need-to-know basis.'

âBe in Tasmania by the end of next week,' said Blacky. âWhen you're there, I will give you more information.'

More

information?

I laughed.

âYou just don't get it, do you, Blacky?' I said. âYou really have no idea how the world of humans works. Well, here is something you

do

need to know. I am twelve years old,

tosh

. I can't throw a few clothes into a bag, book a flight on the internet using my credit card, order a taxi and take off to Tassie at the drop of a hat. I am forced to eat all the green beans on my plate, wear matching socks and wash behind my ears. Now, I have no idea why the dark side of my ears should get particularly dirty. Maybe that's on a need-to-know basis. But I do it because I have to do what I'm told. I can't go to Tasmania, Blacky. I've got to go to school and wash the dishes on Tuesdays and Fridays. This is my world. I can't change it.'

There was silence for about thirty seconds.

âI understand one thing, tosh,' said Blacky. âI understand your school is organising a trip to Tasmania. I even know your dropkick mate Dylan is going.'

I was tempted to ask him

how

he knew, but I was worried he'd tell me I didn't need to know. Anyway, he carried on talking.

âThis is the most important mission I have ever set you, mush. The other two are trivial in comparison. This one will alter history. So I suggest you find a way of getting on that trip. If you are serious about helping the world, you'll be on that boat.'

I was shaken. True, Blacky wasn't above pulling the wool over my eyes. If he thought it would help him he'd shear the sheep and knit the wool himself. The last mission I completed was proof of that. But, somehow, I knew he was telling the truth. This mission was going to be the most important thing I'd done so far. I felt it in my bones.

Of course, knowing this didn't mean I was any closer to getting on the trip. The greatest drawback of having a dirty-white dog as your main informant is the difficulty of getting anyone to take you seriously. âI need to go to Tassie, Miss Dowling. A small, farting dog told me I was going to change history.' Plus, I was aware the trip was only for the special boys unit. But, then again, I was resourceful. It wasn't impossible, particularly if the stakes were as high as Blacky reckoned.

I turned to tell him all this, but the pillow was empty. I could see my window, open about thirty centimetres.

âBlacky?'

Nothing.

I went to the window and raised the sash. The air outside was chilly. The stars were sharp in the sky.

âI'll try, Blacky,' I yelled in my head. âI can't do any more than try.'

There was no reply. I watched clouds drift like smoke against the bone-white moon.

âI'll try, Blacky,' I whispered to the night.

At least I don't have to go any further back in time, which is cool. I was starting to confuse myself.

It was Tuesday morning and I felt depressed. Not even a good kicking from Rose could stir me up. The trip was the day after tomorrow! I sat at the breakfast table, my head down. Concentrating. There was no way now I'd be joining Dyl as part of the official school expedition, so I needed to come up with alternative strategies.

When the going gets tough, the tough get going.

Perhaps I'd have to arrive at school on Thursday and stow away on the school bus going to the ferry. Maybe I could pack myself into Dylan's suitcase. Or I could hitch a ride to Tassie. Pretend to be a dwarf and join a travelling circus. Make my own hot-air balloon. Tie a whole bunch of material together and get Blacky to fart into it.

Hopeless.

When the going gets tough, Marcus loses it.

I dragged myself to school. Depressed. Tonia Niven was waiting at the school gates, mouth full of metal, face splattered with freckles and red pigtails sticking out of her head at alarming angles. She gave me a sickly-sweet smile and my mood, not good to start with, plummeted.

I ran.

Another sound reason to get to Tasmania. Though with Tonia you felt Tassie was never going to be far enough away.

The Principal was prowling the schoolyard like a guard dog. I nearly ran her over in my haste to get away from Tonia. She grabbed the straps of my backpack. For a moment my legs and arms were going in a blur while the rest of me stayed still.

âMarcus,' she said. âWhoa there. Do you still want to go on the camp to Tasmania?'

I allowed my legs and arms to come to rest, like a fan winding down.

âWhat? Yes, Miss. Yes, I do.'

âA boy has dropped out, which means there is a spare place. Come to my office and I'll give you the necessary forms for your parents to sign. But you must get them back to me by tomorrow morning.'