Bless this Mouse (2 page)

Authors: Lois Lowry

"I simply guessed. It was obvious," Hildegarde said with a sniff. Of course it was Roderick who had told her. "That irresponsible little Millicent has reproduced again," he had announced in his arrogant, judgmental way, after he had poked Hildegarde with his nose and completely ruined her afternoon nap.

She peered down at the young mother. "How many litters does this make?"

Millicent cringed in embarrassment. "Four," she confessed.

"Four this year? Or four overall?" Hildegarde gave an exasperated sniff. "Oh, never mind. It doesn't matter. The point is, as Mouse Mistress, I am commanding you to stop this incessant reproduction! It's jeopardizing all of us. And particularly now. Do you realize it's late September?"

Millicent rearranged herself and the mouselets squirmed against her. "Do you mean it will be cold soon? I can make a nest near a heating duct when the furnace comes on."

"That is not at all what I mean. But you

are

going to have to move this litter someplace else right away. I don't think the sexton's here today. But he'll be in tomorrow, I'm sure. And the instant he reaches for his mop..."

Millicent squeaked at the thought.

"Exactly," Hildegarde went on. "Basically, the sexton is fairly tolerant. He'll ignore a few droppings. And I know he overlooked the shredding in his stack of newspapers, though he surely knew it was a nest. That was kind of him. But if he were to encounter...

this!

" She gestured toward the pile of pink mouselets. "Well! Do you recall the Great X?"

Millicent cringed. "I've only heard about it," she said nervously.

"No, of course you don't remember. The last Great X was before you were born. But it was simply terrible. We lost half our population! I vowed not to let it happen again. No more haphazard, willy-nilly reproduction! Careful placement! No visibility!" She looked meaningfully at the litter, sleeping now, curled in the stained mop. "We've got to get you and these mouselets moved inside the wall right away."

She considered the problem, then said, "There's a perfectly good nest left empty after Zachariah's demise." She was silent for a moment, then crossed herself, murmured, "Lord rest his soul," and continued: "It's in the wall behind the men's room toilet. A little noisy, I'm afraid, because of flushing."

"I don't mind flushing," Millicent squeaked.

"Let's get started, then. If you take one and I take another, we can get them all moved in three or four trips." Hildegarde leaned down and took a deep breath. "Oh," she muttered, "this is not pleasant at all." Then she grasped a mouselet by its neck and moved back through the hole into the wall, carrying it carefully, its miniature legs and tail dangling in a slightly wiggly way.

Preparing to come after her, Millicent paused and said in a sulky voice, "Lucretia thinks they're cute."

Hildegarde heard her but didn't dignify the comment with a response. She couldn't stand Lucretia, who had competed against her for the role of Mouse Mistress using unfair tactics, and had been a very poor sport about losing.

She continued on, carrying the mouselet. But now she was even more furious.

Lucretia!

Her rival. Her worst enemy. And a

liar,

too.

Cute?

These mouselets were a hideous shade of pink, and their ribs showed. They were not cute at all.

Praying for Protection

It wasn't simply a problem of placement and visibility. Those things were important, of course, because it was vital that the mouse population remain unseen, and now that she and Millicent had succeeded in moving the mouselets, Hildegarde gave a relieved sigh. Now, at least, the sexton would not open the closet door, gasp, and rush to a telephone to arrange for another Great X.

But it was the timing, too. Late September. They were approaching such a dangerous moment.

"Are

you,

at least, aware of the time of year?" she asked Roderick. "Millicent was completely oblivious." They were in the chancel, seated together at the base of the lectern, dining together on a selection of crumbs and a smear of apricot jam, all of it salvaged from the kitchen wastebasket.

Roderick delicately cleaned one whisker with a paw. He sucked some jam from one of his big front teeth. He and Hildegarde chose different dining places each day, and although the base of the lectern was a favoriteâit was pleasant to lean back against the polished woodâit had the disadvantage of no napkins. When they dined in the sacristy, with all of its stored vestments, there was always an alb or a stole handy for wiping one's mouth and whiskers. He tidied himself as best he could without a napkin. Then he said, echoing Hildegarde, "The time of year."

(Roderick didn't have any idea what she was talking about. But he had found that sometimes, to avoid sounding stupid, it was wise simply to repeat.)

She nibbled her final crumb, and said meaningfully, "The church calendar."

"Yes," Roderick repeated. "The church calendar."

"The Feast of Saint Francis," Hildegarde said meaningfully.

"Of course." Roderick licked a little jam from his paw. "I do love the word

feast,

don't you?"

"Roderick! You do remember Saint Francis, of course? Look

up,

would you?"

Oh, dear. Hildegarde was using her extremely exasperated voice. And she was

pointing.

He tried very hard to recall what she meant. He looked up. Oh, yes. Stained-glass windows. Saints.

He chose one at random, gazed at it ruefully, and hoped he was correct. "Arrows in the stomach! Dreadful. Absolutely dreadful."

She gave him a withering look. "That's Saint Sebastian."

"I knew that," he said hastily. He looked around. There were numerous windows depicting people in

pain of various kinds. But he followed Hildegarde's pointing paw, and suddenly there he wasâhow could Roderick have forgotten?âSaint Francis, the one smiling, with a bird on his shoulder and another eating from his outstretched hand.

"Dear Saint Francis," Roderick said reverently.

"Lover of animals," Hildegarde murmured, gazing at the window where the saint, in his simple brown robe, was depicted in translucent shades of colored glass. Then she shook herself. "Anyway, his feast day is October fourth. You surely knew that."

Roderick smiled politely, hiding his ignorance.

"It's a terribly dangerous time for us. We've had some very narrow escapes on October fourths in the past," she reminded him. "Especially if it rains."

"Indeed. Very narrow."

"Oh, Roderick, you old fool. You don't have any idea what I'm talking about! And," she added, "you have jam on one whisker. Tidy yourself, please, at once."

He did so, and then held his head for her inspection. He so hoped Hildegarde would find him, well, attractive.

But she simply nodded in approval that the jam had been removed. "It's the Blessing of the Animals," she explained impatiently.

Roderick gulped.

Now

he remembered. How could one forget such a frightening event? "Oh my goodness," he said with a shudder. "Cats."

"Exactly. We must pray."

"Now?"

"Now wouldn't hurt. It's probably a good idea to start well in advance."

Roderick nodded, brushed a crumb from his belly fur, bowed his head, and cleared his throat. "Heavenly Father," he began in as humble a tone as possible, "this is a church mouse speaking. We are understandably fearful of cats."

Hildegarde, beside him, murmured her own version, and together they explained the dangerous situation coming up and asked for heightened security and a day with bright sunshine. "If it be Thy will," Hildegarde added politely at the conclusion.

"Yes, of course," Roderick said. "Amen."

***

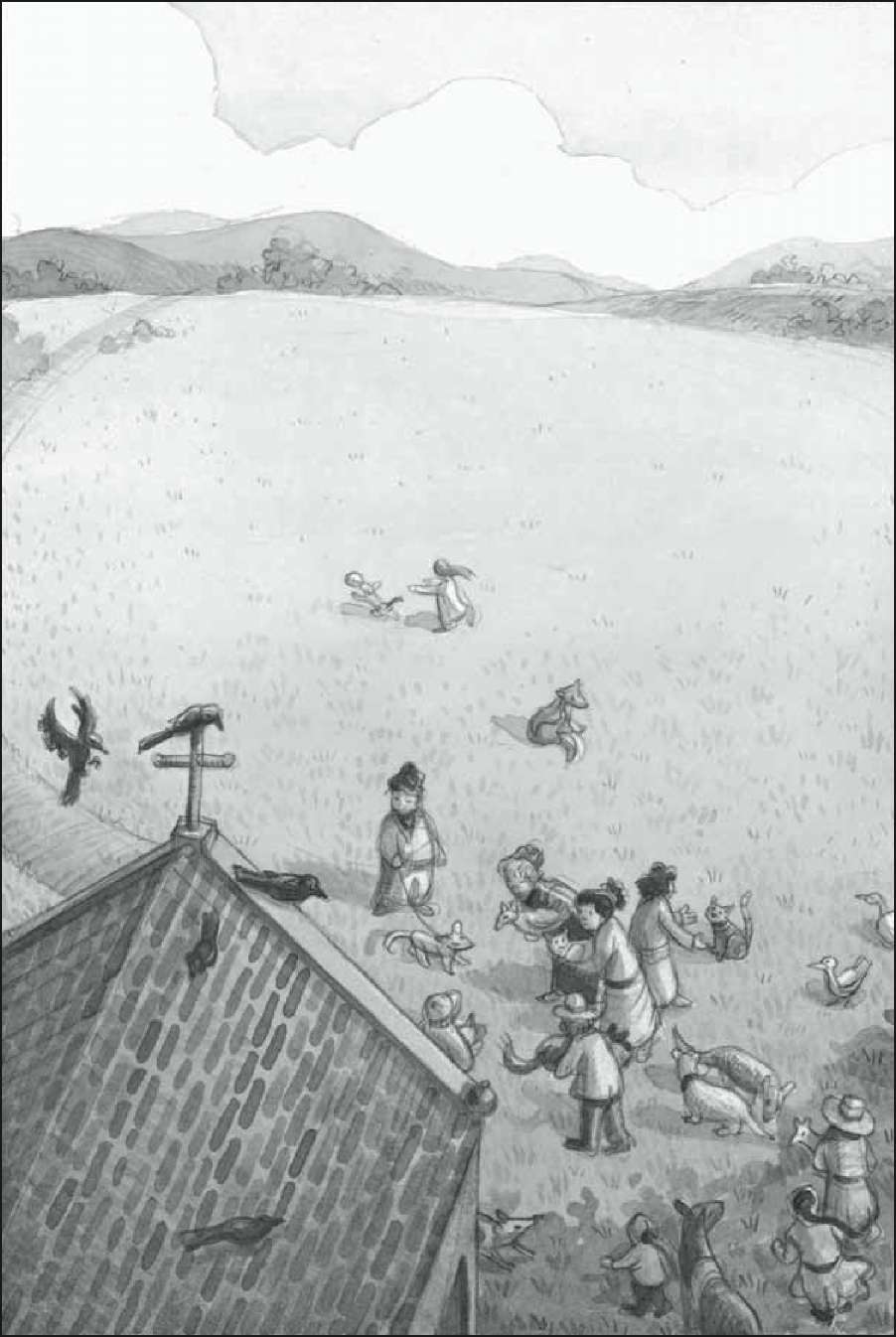

The Blessing of the Animals took place every year at Saint Bartholemew'sâoutdoors, in the churchyard garden, if the weather was good, and fortunately it had been, for several years now. Rain? The whole thing moved inside. For the church mice, a rainy October fourth was much to be feared.

The ceremony was held in honor of the twelfth-century monk Francis of Assisi. Saint Francis had, it was said, so loved all living creatures that he had preached to the birds and they had silenced their twittering, sat very still on their branches, and listened attentively. The stained-glass window indicated that they had sat on his shoulders and in the palm of his outstretched hand, as well, though there is no way to know, after more than eight hundred years, whether that was true.

Each year the parishioners were invited to bring their pets to be blessed. Each year the ceremony had become larger and larger in numbers, and the previous year, the procession had wound out of the churchyard and down the small road that led to the church.

The church newsletter had requested that pet owners, when appropriate, bring scoopers and plastic bags. Golden retrievers, especially, overwhelmed by the magnificence and solemnity, often let loose on the flagstone path.

Cleanup wasn't necessary, of course, for turtles or canaries, and there were always several of both. Children carried cages and terrariums. Dogs walked beside their owners on leashes. Toddlers clutched pet bunnies. Last year a young girl had brought her horse, its bridle entwined with fall asters and ribbons. Walking beside its owner, the horse suddenly paused and peed what seemed to be gallons onto a groundcover of periwinkle. Everyone in the procession waited politely, because there is no way to interrupt a horse mid-pee. The priest, Father Murphy, a passionate gardener, closed his eyes during the wait, and many people suspected he was praying for the survival of his periwinkle. Nonetheless, when the horse, who was by then loudly munching a bouquet of late daylilies that he had wrenched from a decorative border, reached the front of the line, the good father smiled benignly, touched the coarse mane with a few drops of holy oil, and bestowed a blessing.