Blood at the Root: A Racial Cleansing in America (2 page)

Read Blood at the Root: A Racial Cleansing in America Online

Authors: Patrick Phillips

Tags: #NC, #United States, #LA, #KY, #Social Science, #SC, #MS, #VA, #20th Century, #South (AL, #TN, #History, #FL, #GA, #WV), #Discrimination & Race Relations, #State & Local, #AR

When he discovered that many of the “counterprotesters” had come heavily armed, county sheriff Wesley Walraven warned the Brotherhood Marchers that he could no longer guarantee anyone’s safety and urged them to abandon the demonstration. The main group of activists reluctantly climbed back onto the bus, and as they rolled down the on-ramp and headed back to Atlanta, local whites cheered in triumph. Even march organizers like Hosea Williams, among the most hardened veterans of the civil rights movement, were shocked by the scene. Williams had led the first Selma march in 1965, and had survived the attacks of billy-club-wielding Alabama state troopers. Yet there he was, decades later, facing another mob of violent white supremacists. Twenty-seven years had passed since “Bloody Sunday” on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, but Williams knew what he was looking at in 1987: segregation was alive and well in Forsyth County, Georgia.

My mother, father, and sister were among a handful of Forsyth residents who’d marched in solidarity with the protesters that day, and when the buses left, they found themselves face-to-face with hundreds of men who, in the blink of an eye, had turned from a crowd of good ol’ boys and rednecks into a violent mob. Unlike nearly everyone else on the march, my family lived in Forsyth, and when Sheriff Walraven recognized their situation, he hurried my parents and my sister into the back of a police cruiser, where they hunkered down below the windows as men swarmed around the car, screaming, “White niggers!”

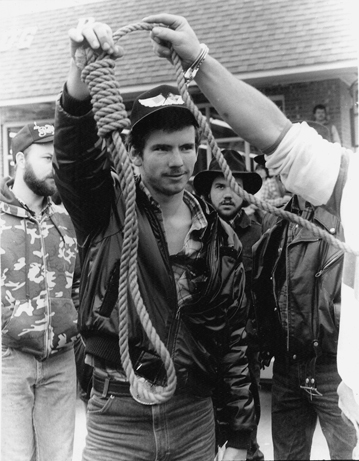

I was sixteen that year and had arrived late to meet my parents for the march. When I finally got to the Cumming square and began searching for them, I found myself shoulder to shoulder with hundreds of other young men walking toward the county courthouse. Only when one of them held up a piece of rope tied

into a thick noose did I realize that I was not at a peace rally but had somehow stumbled into the heart of the Ku Klux Klan’s victory celebration. As I ducked my head and struggled to make my way out of the crowd, I heard the buzz of a microphone switching on. “Raise your hands if you love White Power!” a shrill voice screamed into the P.A., as the people of my hometown surged all around me and howled in unison: “White Power!”

That night, news stations all over the country showed footage of hoarse-throated men yelling, “Go home, niggers!”—followed by shots of Jesse Jackson, Gary Hart, and Coretta Scott King standing at podiums, condemning the violence and bigotry. How, they asked, nearly two decades after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. and only forty miles from his birthplace, could the fires of racial hatred still be burning so fiercely in the north Georgia mountains? The next day’s

New York Times

featured the story on page 1, with a quote from Frank Shirley—head of the Forsyth County Defense League—that made it sound as if, in Forsyth County, Georgia, no time had passed at all since 1912. “We white people won,” he told reporters, “and the niggers are on the run.”

Blood at the Root

is an attempt to understand how the people of my home place arrived at that moment, and to trace the origins of the “whites only” world they fought so desperately to preserve. To do that, we will need to go all the way back to the beginning of the racial cleansing, in the violent months of September and October 1912. That was the autumn when white men first loaded their saddlebags with shotgun shells, coils of rope, cans of kerosene, and sticks of dynamite—and used them to send the black people of Forsyth County running for their lives.

I FIRST HEARD

the story in the back seat of a yellow school bus as it lumbered past the cow pastures and chicken houses out on Browns Bridge Road. My parents bought land there in the mid-1970s, hoping

to escape Atlanta’s vast suburban sprawl and to rediscover some of the joys of small-town life they had known growing up in Wylam, Alabama, just west of Birmingham. The first “lake people” had come north after the damming of the Chattahoochee River formed Lake Lanier in the 1950s, and by the early ’70s young professionals like my parents were just beginning to transform the county into a bedroom community of Atlanta.

Cumming, Georgia, January 17th, 1987

When we moved in the summer of 1977, I was a typical suburban kid. But as soon as I started school in September, I realized that to everyone at Cumming Elementary, I was a city slicker from Atlanta. I’d grown up playing soccer instead of football. I could ride

a bike but not a motorcycle. And one day when I pointed excitedly at a herd of muddy Holsteins, the farm boys all burst out laughing, then just shook their heads in pity.

I had entered a world where nobody liked outsiders. Everyone on the bus seemed to be sitting next to a cousin, or a nephew, or an aunt, and I noticed that a lot of them had the same last names as the roads they lived on. The Pirkles got off at Pirkle’s Ferry, the Cains at Cain’s Cove. And in the mornings, a boy named John Bramblett was always standing with his lunch box next to a sign that said “Doctor Bramblett Road.” Their families had lived in Forsyth for so long that now you could navigate by them like landmarks—all those clusters of Stricklands and Castleberrys and Martins. I still remember my second-grade teacher, Mrs. Holtzclaw, who lived out on Holtzclaw Road, saying at the end of my first day, “G’won now’n’ fetch yer satchel, child.” It was as if, having moved forty miles north of Atlanta, my parents had transported us a century back in time.

As soon as kids heard where I was from, their questions were relentless: Did we live in a skyscraper in Atlanta? Had I ever been to a Falcons game? Did I see a bunch of niggers there? Had the niggers ever tried to kill us?

I’d heard kids call black people “niggers” in my old neighborhood, but my father didn’t allow it, and I’d seen many times how that one word could turn him fierce. I also remembered Rose, the black woman who’d cleaned house for my mother, and I could faintly recall skinning my knee once when no one else was home. Wasn’t it Rose who laid a hand on my back and said, “Alright, it’s gonna be alright,” pressing my face into the cool white cotton of her apron? And I remembered how a dozen women like Rose used to gather on the corner by our house, then walk down the hill and out of sight—back to their own kitchens and their own little boys, in places I knew nothing about, except that they were very far away.

Sitting on the school bus in Forsyth, I understood that for the

kids around me, the color line was drawn not between rich and poor, not between white employers and black servants, but between all that was good and cherished and beloved and everything they thought evil, and dirty, and despised. It was one “nigger joke” after another, and at first I was too afraid to do anything but smile when they smiled and laugh when they laughed. But eventually I got up the nerve to ask my friend Paul why everyone in the county seemed to hate black people so much, especially since there were none of them around.

Paul looked at me in disbelief.

“You don’ know nuthin’, do you, Pat?” he said, slumping down beside me in the bus seat. “You ain’t never heard ’bout the KKK?”

I started to say I had, that I had seen them at a parade once, and that—

Paul just shook his head.

“Long, long,

long

time ago, see, they’s this girl got raped and killed over yonder,” he told me, glancing out the window. “And when they found her in the woods, y’know what they done?”

When I said nothing, Paul spat in the floor, then broke into a wide grin. “White folks run all the niggers clean out of Forsyth County.”

FOR TWENTY YEARS

, that was all I knew: a myth, a legend—or at least the faintest outlines of one. And I admit that long after that day on the bus, when I went to college in the North, I’d sometimes tell the story just to shock people. It was a kind of brag, about how I’d grown up in

Deliverance

country, in an honest-to-God “white county” whose borders were patrolled by gun-toting, rock-throwing rednecks with nooses slung over their shoulders. My classmates were horrified but fascinated, since the story fit every stereotype they’d ever heard about the South and confirmed their sense of being enlightened and evolved compared to all the Jethros and Duke Boys down in Georgia. Yet even after repeating it for years,

after making the tale a staple of my act, I knew little more than I had as a kid, and nothing at all about the real mystery at the heart of Forsyth: those nameless, faceless, vanished people who’d once lived in the place that I called home.

By 2003 I was far from my childhood in Georgia and spending most of my time in the library, doing research on the bubonic plague outbreaks of seventeenth-century London. In those days, archives all over the world were digitizing their collections, and it was still astonishing to me that you could summon up old manuscripts and documents with just a few clicks. The more I searched the historical records, the more I realized that the Internet was becoming a kind of Hubble telescope, aimed back into the past. If you looked through it long enough, and with care, once faint and distant events started to emerge like clear, bright stars.

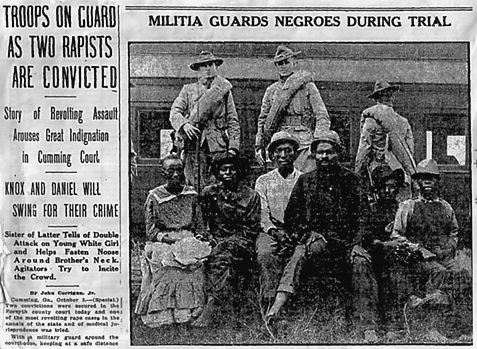

One night I decided to see what the telescope might reveal about the founding myth of my own home place: that old ghost story about a murdered girl and a rampage by white-sheeted night riders. I had always wondered if the whole thing was just a racist fantasy, but when I typed “Forsyth” and “1912” into a database of old newspapers, a list of results came up, with headlines that, sure enough, told of an eighteen-year-old woman named Mae Crow who was raped and killed, allegedly by three black men. “Girl Murdered by Negro at Cumming,” one front page read. “Confessed His Deed . . . Will Swing for Their Crime,” said another. I clicked a link that led to an article in the

Atlanta Constitution

, which slowly knit itself into an image. When it filled the screen, I stared in wonder.

I’d thought of the story of Mae Crow’s murder as a kind of tall tale all my life and had even questioned whether African Americans ever

really

lived in Forsyth. But now I was suddenly confronted with the truth—or at least something closer to it than I ever thought I’d get: three white soldiers in front of a train car, standing guard over six black prisoners. These were the first faces of black Forsyth I had

ever seen, and while there was no way to know if they were really guilty of the “revolting assault,” when I zoomed in and panned across the photograph, I could hardly believe my eyes. Young, fearful, as alive as you and I, the prisoners stared back at me from the very twilight of that old world, and at the dawning of the all-white place I knew. As they peered across the century, frozen there beside the train tracks, I couldn’t shake the feeling that the image came to me bearing not just a secret but an obligation.

Atlanta Constitution,

October 4th, 1912

As I read more about the accused, I realized that the picture raised more questions than it answered. If two of those faces belonged to the “Knox and Daniel” who were doomed to “swing for their crime,” which two? And if they were the ones who stood accused of raping and killing Mae Crow, who were the others? That teenager in the middle wearing a porkpie hat, his limbs growing so fast that his white shirt was already a size too small? What about the

young boy on the right in overalls, resting an elbow on the thigh of an older, visibly worried man? And who was the lone woman, petite and fine-boned, who seems to be—maybe I am imagining this—almost smiling? Was it really true, as the headlines claimed, that she had helped “fasten the noose” around the neck of her own brother? And who was that big man in front: legs spread, arms gripping his knees, as if to shield the group?

This book began with my first glimpse of that photograph, and my realization that while the stories I’d heard were riddled with lies and distorted by bigotry, at their heart lay a terrible, almost unbearable reality. These were real people being led to real deaths, at the start of a season of violence that would send a ripple of fear out across the twentieth century. In the glow of that computer screen, I also began to see how the tale, stripped of names and dates and places, made the expulsion of the county’s black community seem like only a legend—like something too far back in the mists of time to ever truly understand—rather than a deliberate and sustained campaign of terror.