Blood at the Root: A Racial Cleansing in America (3 page)

Read Blood at the Root: A Racial Cleansing in America Online

Authors: Patrick Phillips

Tags: #NC, #United States, #LA, #KY, #Social Science, #SC, #MS, #VA, #20th Century, #South (AL, #TN, #History, #FL, #GA, #WV), #Discrimination & Race Relations, #State & Local, #AR

Having lived my entire life in the wake of Forsyth’s racial cleansing, I wanted to begin reversing its communal act of erasure by learning as much as I could about the lost people and places of black Forsyth. I was determined to document more than just that the expulsions occurred: I wanted to know where, when, how, and to whom.

It was then I set myself the task of finding out what really happened—not because the truth is an adequate remedy for the past, and not because it can undo what was done. Instead, I wanted to honor the dead by leaving a fuller account of what they endured and all that they and their descendants lost.

BLOOD

AT THE

ROOT

O

n Thursday, September 5th, 1912, Ellen Grice let out a terrifying scream. Some say this occurred at the house of her parents, Joseph and Luna Brooks, others that Grice was at her own home when her husband, a young farmer named John Grice, came in “about midnight and found his wife, and at once sounded an alarm.” A century later, there is no way to know exactly what led to her cry for help, who first heard it, or what transpired in the minutes after. But soon newspapers all over the South were telling readers what Ellen Grice said then: that she had been “awakened by the presence of a negro man in her bed.”

When they heard Grice’s story of a black rapist forcing his way through an open window, the white men of Forsyth County didn’t waste time asking a lot of questions. By the next morning, the news had spread from house to house, country store to country store, and all of white Forsyth was in an uproar. When word reached the county seat of Cumming, a team of bloodhounds was assembled and a posse of white men were deputized on the spot. As they saddled their horses and rode off in search of Grice’s attacker, they were led by a man who would play a central role in the bloody “race troubles” to come: Sheriff William Reid.

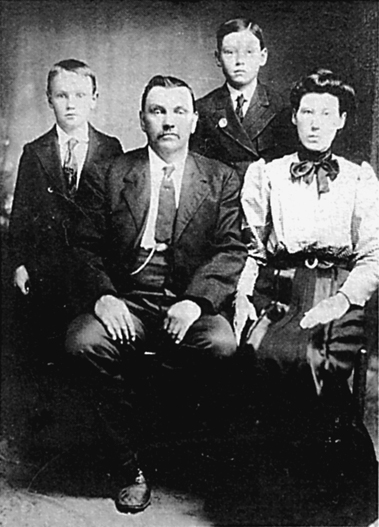

Bill Reid turned fifty in 1912 and was in the middle of his second term as sheriff of Forsyth. The job had brought a major improvement in his family’s fortunes, and a portrait taken around the time of his election shows just how quickly Reid transformed himself into one of Cumming’s leading citizens. As they pose in a photographer’s studio, Reid’s young sons wear double-breasted suits and silk ties; his wife, Martha, is dressed in fashionable satin; and Reid himself—with his dapper tie pin and pomaded hair, his coat thrown open to reveal a gold watch chain—looks like anything but a hayseed just in from the fields.

But that’s precisely what he’d been when he took office in 1906, having grown up on his father’s farm, where the Reids raised corn and hogs and struggled through the lean years, like everyone else working the tough red clay of the Georgia foothills. Having quickly made a name for himself in town, Reid wore his badge and revolver with a certain amount of swagger and was in no hurry to return to the family farm. And while contemporary newspaper accounts make it clear that he was the face of the law in Forsyth, Reid’s name also appears on an obscure but no less significant document from those days: a yellowed sheet of onionskin that a secretary fed into the platen of her Underwood in the 1920s. Across the top, she typed, “KNIGHTS OF THE SAWNEE KLAVERN OF THE KU KLUX KLAN.” Below, among the names of a hundred charter members, is Forsyth County Sheriff William W. Reid.

REID’S CHIEF RIVAL

in the 1912 election had been his own deputy, Mitchell Gay Lummus. A leaner, younger man at thirty-four, he was the grandson of a Confederate war hero named Andrew Jackson Lummus. The farm in Vickery’s Creek where Lummus grew up was surrounded not only by white neighbors but also by a number of well-established black farmers, including Jasper Gober, Archibald Nuckolls, and Isaac Allen. By the summer of 1912, Lummus,

too, had set his sights on the job of county sheriff. He was undoubtedly looking to move up in the world, like Reid, but Lummus also needed the money. His wife, Savannah, had died of meningitis in 1909, and he’d had no choice but to hire a live-in nanny to help raise his three young and suddenly motherless girls: Lillie, eleven, Jewell, eight, and Grace, three. A hopeful Lummus declared his candidacy in May of 1912, but lost to Reid that July.

Sheriff Bill Reid c. 1908, with wife, Martha, and sons William and Robert

And so it was the stout and garrulous Bill Reid, not tall, quiet

Gay Lummus, who sat in the sheriff’s office in the early hours of Friday, September 6th, listening to the tale of Ellen Grice’s “outrage” at the hands of a black rapist. By midmorning, Reid and his posse had ridden eight miles south of Cumming and arrived at a cluster of tenant farms near Ellen Grice’s house. When a group of young boys tore down the road, yelling that the sheriff was coming with a pack of bloodhounds, the black field hands and sharecroppers of Big Creek knew enough to get out of sight. Lummus was second-in-command, and so it fell to him to dismount and pound on doors, demanding that one family after another come out into the yard and speak with the sheriff.

By sunrise on Saturday, September 7th, Reid and Lummus had arrested and jailed a teenager named Toney Howell, along with four other men held as accomplices: Isaiah Pirkle, Joe Rogers, Fate Chester, and Johnny Bates. Howell was the nephew of two of Cumming’s most respected black residents, Morgan and Harriet Strickland, and was staying on the farm they owned in Big Creek, to provide some much-needed help during the fall harvest. What the other prisoners had in common was that they were unmarried, illiterate black men who happened to live near the scene of the “dastardly assault.” The

Macon Telegraph

hinted at the arbitrary nature of their arrests when a reporter wrote that the posse had ridden out to Big Creek and “rounded up suspects.”

Toney Howell also stood out for having been raised not in Forsyth but in neighboring Milton County. Much like Emmett Till in Money, Mississippi, forty-three years later, this made him conspicuous as the stranger in the group, and one of the few black faces in Big Creek unknown to Reid and Lummus. The

Atlanta Georgian

would later admit that the evidence against Howell was entirely circumstantial, and in 1912 the very definitions of words like “assault” and “rape” were kept deliberately vague and used to describe almost any incident involving black men and white women.

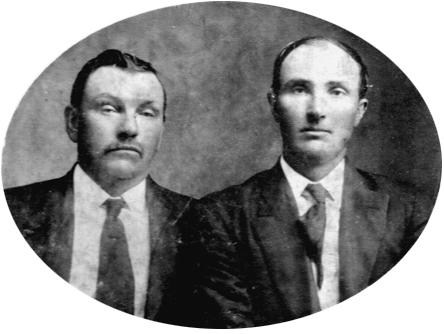

Sheriff Bill Reid and Deputy Gay Lummus, c. 1912

This means that once Toney Howell stood accused of having entered Ellen Grice’s bedroom, he was widely regarded as being guilty of some kind of sexual “assault,” whether or not he had actually been there, and whether or not he had ever touched Grice. “If a lynching takes place,” said one journalist, “Toney Howell will probably be the victim.” In the Jim Crow South, this was the kind of reporting that functioned not just as a prediction but as a directive to potential lynchers.

By lunchtime that Saturday, the town of Cumming was bustling with families from outlying sections, making their weekly trip to market. With Howell and four other black men locked in the Forsyth County Jail, talk of Ellen Grice was on everyone’s lips. But “no excitement prevailed,” according to the

Georgian

, until Grice’s father, Joseph Brooks, arrived in town, bringing word that his daughter was in “critical condition” from the alleged attack out in

Big Creek. This news had an electrifying effect on the crowd, and soon a group of whites gathered around the little brick jailhouse on Maple Street and demanded that the prisoners be brought out. As more and more people arrived at the square, the town buzzed with what one reporter called “a determined spirit of speedy vengeance.”

PICKING HIS WAY

through that crowd, the Reverend Grant Smith must have looked like any other “hired man” in Forsyth. At forty-eight, he was part of the county’s poor black underclass, a group that, though they represented 10 percent of the total population, were almost totally disenfranchised by the Jim Crow laws of Georgia. While emancipated slaves had been guaranteed the right to vote by the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870, the Georgia legislature countered by adopting the nation’s first cumulative poll tax in 1877, then established one of the first “white primary” systems in 1898. The result—in a place where the vast majority of African Americans could not afford the poll tax, and where Democratic primary winners were, almost without fail, elected to office—was that men like Grant Smith had no chance of representation in the local government and virtually no power to resist the will of the white majority.

Smith earned his living picking corn and cotton in the rolling, terraced fields of the county, and it’s likely that on the morning of the “excitement” he was helping bring an employer’s harvested crops to market. But to black churchgoers, he was also well known as a preacher, and as the son of Reverend Silas Smith, one of the area’s leading clergymen, whose ornate signature had graced the bottom of “colored” marriage certificates during Reconstruction. Silas and Joanna Smith’s oldest son, Grant had been conceived in the chaotic war year of 1863 and was part of the very last generation of African Americans born into slavery. Though he was too young to remember it, Grant Smith was the only one of his nine siblings who began life as the legal property of a white man.

But having been born on the eve of emancipation also meant that Smith’s earliest memories included going to one of the freedmen’s schools that sprang up all over Georgia after the Civil War, when northern aid societies and the federal government succeeded in establishing a right to education for Georgia’s former slaves. As a result, unlike his younger brothers and sisters, who came of age after the end of congressional Reconstruction—and after the colored school system was dismantled in north Georgia—Smith could read and write. There was no outward sign of it as he shouldered his way past farmers, tradesmen, and merchants hawking their wares on the Cumming square, but during that brief window of hope in the early 1870s, Grant Smith had become something white Georgians feared almost as much as a black rapist: an outspoken, educated black man.

WHEN HE LEARNED

that Morgan Strickland’s nephew Toney had been accused of rape, and heard white men all around him whipping themselves up into a lynch mob, at some point Reverend Smith turned to someone in the crowd and said exactly what he thought. It was a shame, he said, that so much trouble was being caused on account of a “sorry white woman.”

The words were barely out of Smith’s mouth before white men all around him froze mid-sentence, stared at each other in disbelief, then tightened their fists around the buggy whips and leather crops with which they’d driven into town. Unable to reach the prisoners inside the jail, and outraged by the alleged attack on Grice, they now saw a target much closer to hand: the book-smart, headstrong, “uppity” black preacher, who had dared to question a white woman’s worth. “News of what he had said spread,” according to one witness, and “like a flash . . . the infuriated mob was upon him.”

The first crack of leather brought people from every direction, eager to push their way into the ring of men surrounding

Smith, who was now being whipped, kicked, and punched by every fist that could reach him. Estimates put the size of the mob at three hundred, and those on the outskirts could barely hear Smith’s grunts and cries over the cheering and shouting. When one group of sweat-soaked men tired, they gave way to others, who moved in and took their turn. Witnesses said the preacher was beaten “nearly to death” and that others started gathering scraps of wood for a bonfire, on which they planned to burn Grant Smith alive.

Before they could, Sheriff Reid and Deputy Lummus muscled their way through the crowd and somehow managed to wrest Smith away. They carried him to the courthouse, where he was at first locked inside a huge basement vault—not so much to keep him in as to keep potential lynchers out. After hearing Smith’s moans, Reid finally agreed to move “the prisoner” upstairs, where a doctor was summoned to treat and dress his wounds.

It was around this time—as the bloody, half-naked body of the preacher was carried past his office door, and as a crowd of hundreds bellowed for Smith to be handed over—that Mayor Charlie Harris realized he needed help. If he wanted to save Grant Smith and the five black men in the Cumming jail from a lynch party that was growing larger and more determined by the minute, Harris knew he would need more than a skinny deputy like Gay Lummus and a glad-handing, good ol’ boy sheriff like Bill Reid. Rising from his chair, Cumming’s mayor tapped the little brass lever of a telephone on his desk and told the operator to commandeer all outside lines for an urgent call to Governor Joseph Mackey Brown, in Atlanta. As Harris pressed the receiver to his ear and waited, Sheriff Reid stood nearby, scanning the faces in the mob—and finding among them, no doubt, a great many men who would soon join him in the Sawnee Klavern of the Ku Klux Klan.