Blood Brotherhoods (83 page)

Read Blood Brotherhoods Online

Authors: John Dickie

All you have to do is set up good relationships with a few local administrators. When the Sicilian regional government puts a contract out to tender, there are men linked to Cosa Nostra who manage the negotiations. That way ghost companies win the contracts and pass them on to the mafia group hiding behind them. To give you an idea of the profits: if a contract is worth a billion lire [$2.2 million in 2011], 10 per cent goes to the politician who obstructs the competition and makes sure the contract goes to the right people, and the rest goes to a

mafioso

who will double his money in a year.

Mutolo proved an obedient underling to his boss, Saro Riccobono of the Partanna-Mondello Family. All was progressing well with a good, but unexceptional, mafia career.

Suddenly, in 1975, a new business exploded, a business that would earn the mafia more than tobacco smuggling, kidnapping and construction put together. Mutolo remembers being in a meeting, chatting with other Men of Honour about routine extortion rackets, when Tano Badalamenti burst in. ‘Gentlemen, we have the chance to earn ten times as much with drugs.’ Badalamenti, head of the Palermo Commission, well connected in the United States, had spotted the gap in the market created by President Nixon’s war on drugs, and he was perfectly placed to exploit it.

Initially, Cosa Nostra stepped up its involvement in heroin through the same channels it used to smuggle cigarettes. The merchandise travelled in the same containers as the ‘blondes’. Palermo Families pooled their investments in joint-stock ventures in just the same way as they had done for major cigarette cargoes. Payments were made through the same Swiss banks that were used to pass money to some of the major tobacco multinationals. As Mutolo quipped, ‘If there are any rascals in the story, it’s the Swiss.’ Tano Badalamenti himself took charge of the first expedition to meet suppliers in Turkey. The scheme was a roaring success. Within forty days, all of the investors had tripled their money. Cosa Nostra’s heroin rush had begun.

Mafiosi

plunged headlong into the tide of white powder, adapting their old techniques of networking and corruption, and rapidly acquiring lucrative

new skills. Nunzio La Mattina, a Man of Honour from the Porta Nuova Family, underwent retraining of a historically resonant sort. Where he had once used his knowledge of chemistry to test the exact composition of Sicily’s lemon juice, now he became a large-scale heroin refiner. Other

mafiosi

learned the same trade by taking lessons from Corsicans who were brought over from Marseille. Among them was Francesco Marino Mannoia, from the Santa Maria di Gesù Family. Each time a bulk delivery of morphine base arrived, Marino Mannoia would spend a week at a time amid the vinegary fumes of one of many laboratories that had sprung up across the island. When he emerged, his skin would be scaly and his lungs scoured. He was known as ‘Mozzarella’ because he was simple and unflashy, and in restaurants always ordered mozzarella and tomato salad, the simplest and safest item on the menu. His personal habits did not change even when, as Cosa Nostra’s most important chemist, he became fabulously rich.

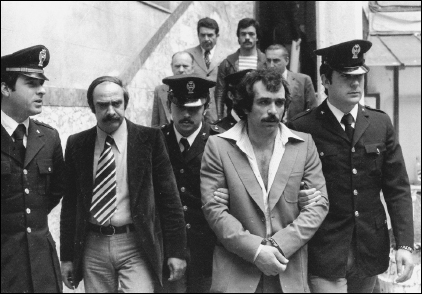

Mr Champagne. Gaspare Mutolo became one of Cosa Nostra’s leading heroin brokers in the 1980s. With him (left, with striped tie) is Boris Giuliano, a brilliant policeman murdered later in 1979.

Gaspare Mutolo chose another specialism: he became a broker, contacting the wholesale suppliers in the Near and Far East, bringing batches to Sicily and selling them on to traffickers within Cosa Nostra who had access to America. As a leading heroin broker, Mutolo had a reliable map of the politics and economics of the mafia’s trafficking. What that map shows is that Cosa Nostra did not enter the heroin business en bloc. Nor was it transformed into a top-down multinational dope corporation by the late 1970s

heroin boom. Rather it acted like what it is, and what it has always been: a Freemasonry of criminals. Each individual member of the club, each little network of friends within it, each of its Families, and each of the high-level coordinating structures like the Palermo Commission, had the capacity to carve out a role. As Mutolo would later explain:

When it comes to drug trafficking, if deals are small then they can be managed by a Family. Everyone is independent and does what they want. But sometimes someone gets involved in a big consignment that could interfere with other

mafiosi

and their work, with what a whole organisation is doing. Some big deals can take over a whole market. In such cases the Commission may intervene. Members of the Commission can step in to impose organisation on the deal. So the Commission intervenes in all the most important sectors.

A kind of internal market among Men of Honour developed. Some wholesalers would sell consignments of morphine base to refiners they knew in the brotherhood. When it had been transformed into heroin, they would then buy it all back from them. Often the Family bosses did not deal directly in heroin at all, but were content to sit back and ‘tax’ the dealers they knew: a much less risky way to make money.

In 1976, just as his heroin ventures were really taking off, Mutolo was arrested; incarceration brought a quantum leap in his criminal standing. ‘God bless these prisons!’, he later proclaimed. Mutolo’s cell mate in Sulmona in central Italy was a long-haired Singapore Chinese heroin importer called Ko Bak Kin. Though neither spoke the other’s language, Mutolo took a liking to Kin. Over shared meals and through little gestures of generosity, they began to develop the most valuable thing in the treacherous world of international narcotics dealing: trust. When Kin had learned enough Italian to talk business, he said to Mutolo: ‘Gaspare, promise me: as soon as you get out, call me. I’ll let you have all the drugs you need.’ In 1979, just before Kin’s sentence ended, Mutolo gave him his gold watch and jewellery to pay for somewhere to stay in Rome, and for a plane ticket to contact his suppliers in Thailand. Kin reciprocated by leaving Mutolo a post-box address in Bangkok.

Soon afterwards, in 1981, Mutolo himself was allowed out on day release. To reintegrate him with the world of honest work, he was allotted a job in a furniture factory in Teramo, in central Italy. But the position of assistant bookkeeper was not best suited to Mutolo’s abilities, so he persuaded the owner to make him the factory’s Palermo agent. He was also granted periods of leave in Sicily for ‘family’ reasons. Mutolo had his Ferrari Dino and

his Alfa Romeo GTV 2000 brought up to Teramo, so he would roar down to Sicily for his business meetings. He also rented a huge villa by the sea near Teramo, and used a suite in the five-star Michelangelo Hotel as his office. From there he would make calls to Australia, Brazil, Venezuela and Canada.

Mutolo’s drug business rocketed. He quickly put together an organisation of common criminals, friends and relatives to handle the hundreds of kilos of heroin imported from Thailand by Ko Bak Kin. When the authorities began to discover some of the Sicilian laboratories, Mutolo and Kin latched on to a scheme that would make refining much safer, and put even more links in the supply chain into their hands. Kin sourced the morphine base in Thailand. A mafia partner of Mutolo’s arranged for it to be transported to Europe by ship. On board, there would be a Man of Honour from Mutolo’s Family of Cosa Nostra to act as guard. Just as importantly, there would also be a chemist, so that the heroin—as much as 400 kilograms in one go—was ready to put on the market as soon as it arrived.

‘1981: my magic moment, the best year of my life,’ Mutolo remembered. Armani suits, silk scarves, designer shoes, Cartier watches for his friends . . . Among the lawyers, doctors and professors of Teramo whose company he kept, Mutolo became known as ‘Mr Champagne’. Today, having turned state’s evidence, he lives a humble life under an assumed identity, and rides a scooter rather than driving a Ferrari. So perhaps it is understandable that he is nostalgic for the luxuries of his past. But he knows deep down that these were fripperies. The phone taps and other evidence that would eventually convict him of heroin trafficking show him carefully using his wealth to dispense favours and make friends. To avoid political tensions within Cosa Nostra, Mutolo made sure that the Palermo Families always got the chance to invest in a new cargo, and that the heroin reaching Sicily was distributed fairly. Mutolo kept his boss happy. He rose in Saro Riccobono’s estimation, becoming one of the leading members of the Partanna-Mondello Family. In the end, in Cosa Nostra, money means nothing unless it is converted back into power.

The huge amounts of cheap heroin being channelled through Italy in the 1970s caused an explosion of drug use in the peninsula. In 1970, the presence of a heroin problem had barely registered. By 1980, Italy had more heroin addicts per head of population than did the United States. Anyone who visited a major Italian city in the 1980s can remember the sight of plastic syringes littering the gutters in quiet streets.

Despite the growth in Italian domestic consumption (and therefore in overdose fatalities), the United States market remained the biggest consumer market in absolute terms. Gaspare Mutolo was a big player in the complex pass-the-parcel game of trafficking heroin from the East, through Sicily, and into the United States. But he was a long way from being the biggest. In fact, Mutolo learned very quickly that the

mafiosi

who occupied the most strategic place in the supply chain to America were the ones who straddled the Atlantic.

T

HE

T

RANSATLANTIC

S

YNDICATE

O

N

22 A

PRIL

1974,

A SMALL GROUP OF MAFIOSI SAT DOWN TO CHAT IN AN ICE-CREAM

bar in Saint-Léonard, Montreal’s Little Italy. Two of them led the discussion. One was the bar’s owner, Paolo Violi, underboss of Cosa Nostra in Quebec. Violi’s guest had come directly from Sicily: he was Giuseppe ‘Pino’ Cuffaro, a Man of Honour who also hailed from the province of Agrigento. The two spoke a common jargon of mafia power politics. A jargon that—through a hubbub of background conversation, a clatter of crockery and the hiss and crackle of a secret microphone—Canadian police were able to record.

Violi began the pleasantries: ‘So the journey went well then? Let’s kiss one another.’

In reply, Pino Cuffaro could hardly wait to unload his news from Sicily. ‘Well, Paolo, before you drink this cappuccino, I’ve got to announce a nice surprise, an affectionate surprise that is naturally close to our hearts . . . Carmelo has been made representative in our village.’

Then, between sips of coffee, there followed a long bulletin on the latest Cosa Nostra appointments in the far-off province of Agrigento. Who was provincial boss, who were the

capomandamenti

(precinct bosses), who were the

consiglieri

, and who had been initiated. They discussed the state of Cosa Nostra across Sicily, remarking on how the Palermo Commission was still suspended. And they dropped the names of mutual friends, like don ’Ntoni Macrì—the ’ndrangheta boss from Siderno who was also a member of Cosa Nostra (and who, unbeknownst to all, would enjoy his last game of bowls just a few months later).

But Pino Cuffaro had not come all the way to Quebec just to bring his Canadian friends up to speed with the ins and outs of the old country. He had come to resolve a delicate issue of diplomatic protocol. Could a Man of Honour from Sicily arrive in America and assume full citizenship of the Cosa Nostra community there? Underlying this question was the fundamental issue of whether Cosa Nostra was a single transatlantic brotherhood, or whether the American and Sicilian branches were separate entities. The positions were so entrenched, and the argument so strained, that the men had to meet twice.

Paolo Violi, the Canadian gangster, argued for a five-year rule: any Sicilian who arrived in Canada would have to spend five years being monitored before he was granted full status. The Sicilian visitor wanted no barriers to be put up between Sicily and the New World.