Blood Work (5 page)

Authors: Holly Tucker

As the work of Willis, Wren, and Lower demonstrates, Harvey's discovery of blood circulation in the late 1620s set off a chain of questions and experiments that, with the benefit of

historical hindsight, clearly set the stage for transfusion. Still, important and unresolved issues regarding the exact nature of bloodâespecially questions of the exact location of the soul and the extent of animal and human differencesâwould continue to linger in the background. It would take another year or more for these questions to return front and center on the biomedical stage, but when they did the results would be deadly. In fact this showdown on matters of the soul might have taken place earlier had Lower been able to push forward with his next experiments as he intended. But, just as he was getting started, a devastating plague and the Great Fire of London got in his way.

PLAGUE AND FIRE

T

he heavens glowed with a streak of heat as a comet blazed across the night sky. It arrived suddenly one winter evening in 1664 and shimmered across a dark background of stars for nearly two months. The fiery globe loomed over Europe as if taunting astronomers to chase it. In a celestial game of hide-and-seek, the comet first revealed itself to Spanish stargazers on November 17. It peeked out of the gray Dutch clouds on December 3, and on December 14 the comet made itself known to the astronomer Johannes Hevelius at his home in Poland. Then it made a mandatory stop at Cambridge so that Isaac Newton could have a glimpse of its striking long tail. In an order that felt as if the stars were playing favorites, the comet was at last spotted in French skies several days later and soon reached its maximum brightness on December 29.

1

Once the comet appeared its presence was something of a beacon. It was visible to the naked eye, and its ostentatious hovering struck dread and foreboding in the hearts of those who looked up fearfully toward the glowing light. “Bearded stars,” as Aris

totle called them, were harbingers of doom.

2

They announced the coming of any number of calamities: drought, famine, earthquake, flood, economic disaster, war, plague, and even the Second Coming. In the comet's wake cathedral bells chimed, priests found new converts, and parents kept their children under a more watchful eye. “Death comes with those celestial torches,” wrote one Stoic poet, “which threaten earth with the blaze of pyres unceasing, since heaven and nature's self are stricken and seem doomed to share men's tomb.”

3

The longer the comet lingered overhead, the longer the impending suffering would last. Since the ancient astronomer Ptolemy, star watchers had posited elaborate correlations between the length of future disasters and the time that the comet remained in the sky. And some cometary prognostications were dire. William Lilly, author of

England's Propheticall Merlin,

warned his readers that a year of disaster would ensue for every day a comet was observed.

4

Little wonder that the whole continent breathed a sigh of relief when the November 1664 comet sputtered slowly out of sight two months after it began haunting Europe.

If the superstitious read on the 1664 comet was dim, the scientific view of these astronomical anomalies was strangely bright. In January 1665 the College of Clermont in France held an unusual conference to discuss the current state of comet research and to put forth the next steps for study of the composition, trajectory, and origins of comets in anticipation of when another one would make its dramatic appearance. They did not have to wait long. In March a new comet swooped into view. Dread turned to full panic among the populaceâand for good reason. “This comet,” declared astronomer John Gadbury, “portends pestiferous and horrible windes and tempests.”

5

How right he was. In just a few short months the comet made good on its horrific promises. In

April 1665 a pervasive viral hemorrhagic feverâthe plagueâswept through London.

Celestial shows aside, London was an ideal setting for such a disaster. The city's tight medieval streets had long been pushed to their limits. Inhabitants elbowed and jostled one another in a futile attempt to claim personal space. Too wide for the narrow passageways, carriages scraped facades of wooden buildings, leaving lines of splintered scars in their wake. Peace and quiet had been nearly impossible to find within the city walls and, even where they could be found, required nothing short of a king's ransom to enjoy. As the diarist John Evelyn complained, “As mad and loud a town is nowhere to be found in the whole world.”

6

If a relentless din battered the ears, stench assaulted the nose. Dogs and pigs roamed the streets freely. Raw sewage flowed everywhere but the “kennels,” or channels, dug in the ground to direct rainwater and effluvia. (For obvious reasons sturdy foot scrapers were installed beside every entrance door.) The city was, Evelyn wrote, wrapped in “clowds of Smoake and Sulpher, so full of Stink and Darknesse.” Slaughterhouses coexisted alongside family residences; candlemakers filled the air with the smell of putrid tallow. Sparing no criticism for his home city, Evelyn explained that even churches offered little respite; “coughing and snuffingâ¦and barking and spitting” were “incessant.”

7

Illness was part of daily life in London, and the capital was ripe for the devastating plague that struck in April 1665. It began slowly enough, with just a few deaths in the city's outlying communities. But in mid-June it hit London with full force. And by the fall of 1665, nearly one hundred thousand people, 20 percent of the city's inhabitants, were dead. Another two hundred thousand fled to the countryside to escape the pestilence. Of those more than 50 percent would soon be struck as well.

8

With the city's mazelike streets now emptied of their usual crush of noise

and dust, London had become a ghost town. There was “a dismal solitude in London-streets,” wrote the Reverend Thomas Vincent, “a deep silence almost in every placeâ¦no rattling coaches, no prancing horses, no calling in customers, nor offering Wares; no London cries sounding in the ears; if any voice be heard, it is the groans of dying persons, breathing forth their last.”

9

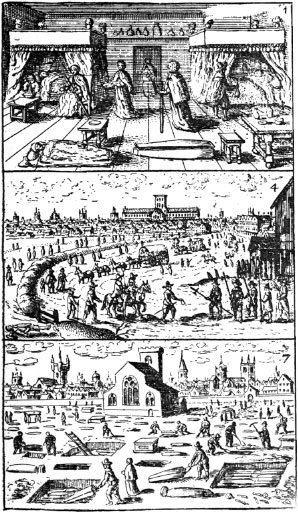

FIGURE 5:

Images of the London plague (1665). illness at home, looting, Londoners in boats on the Thames fleeing from the city, Londoners refused entry to villages in countryside, death carts and burials of plague victims in the capital city, ending in the return from the countryside to London.

Bloated bodies were thrown into open plague pits. On those corpses that had been retrieved shortly after death, the “buboes”âthe plague's signature swellings at the neck, under

arms, and groinâwere still visible. In the heat of the approaching summer others had decomposed into a reeking stew of death that looked anything but human. Unable to keep up with the passings they intended to mark, church bells rang unceasingly through the city's parishes, sending shudders through the few souls who still remained there.

10

In the month of September alone, at the height of the plague, bills of mortality confirmed that nearly 7,000 of the 8,252 bodies taken away in “dead carts” were plague victims.

11

How the dis

ease spread was anyone's guess. We know now that the bubonic plague is caused by

Yersinia pestis

, a bacterium that is transferred to humans through fleabites. But the seventeenth century would have had no idea of the scourge's origins; germ theory was still more than two hundred years away. Instead miasmaâcorrupt airâwas thought to be the primary suspect.

12

Rotten food, musty rooms, flooded fields, the exhalations of the sick, and the decaying corpses of the deadâall conspired to bring illness to those who breathed the fetid air. And in an era where “horrid stinks” and filth claimed every corner, city dwellers were rarely treated to “wholesome” air.

13

Army and city officials ordered that fires be lit on every street in a frantic attempt to clear the air. Plague doctors covered neck to toe in black garments walked the city. Their heads and faces were veiled in beaklike masks under which they could be heard hacking and coughing. At the ends of those beaks incense smoldered, in an effort to protect their wearers from the noxious miasma of pestilence. Members of this sinister aviary set upon the suffering city, and they crossed thresholds of homes that no one else dared to enter. Through the glass-eyed openings of their masks, they confirmed that death had staked its claim on a household and began the task of fumigating. Personal items were set afire, the body collectors were called, and the exterior of the house was marked by a double cross: the plague cross.

By early November 1665 the curse began to lift, and by January 1666 streams of exiled Londoners returned home on foot, tired and traumatized. London was still grieving its losses, but life in the bustling city gradually returned to some semblance of normal. And as the streets slowly filled again with people, so too did Lower resume his blood experiments. One wintry February day in 1665 the ever-serious Lower strapped two dogs onto a table. “I tried,” he later wrote, “to transfer blood from the jugular vein of one ani

mal to the jugular vein of a second by means of tubes between the two.” But no blood flowed; it clotted “at once” in the tube. Lower quickly emptied the tubes and tried to reinsert them another way, again with no success. “I finally determined to transfer blood from the artery of one animal into the vein of a second.”

14

Lower later positioned two dogsâthe neck of one to the neck of the otherâ

on a table and began by delicately exposing the carotid artery of the donor. He tied a loose knot around the artery in two places, one above where he intended to draw blood and one below. Then slipping two threads under the artery, he lifted it up ever so carefully so as not to stretch or strain the blood vessel. Scalpel in one hand, a large quill in the other, Lower crouched over the writhing animal. Steadying himself, the surgeon quickly nicked a small opening in the artery and, in one deft move, slid a quill into the pulsing vesselâand then hurriedly attended to the recipient. There, he performed the same choreographed sprint, this time on the jugular vein. Into the recipient he inserted not one but two different quills. The first would be used to connect the recipient's vein to the donor's artery. The second would allow the dog's own blood to be emptied out into a shallow dish.

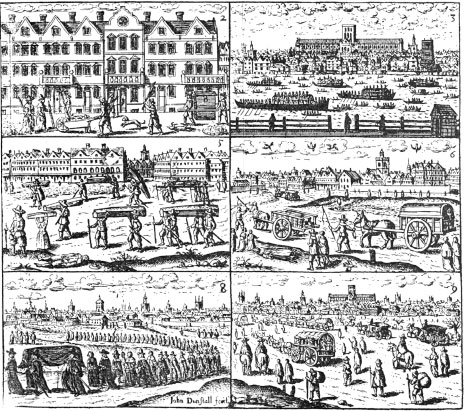

FIGURE 6:

Typical apparel of plague doctors and other officials who entered plague-stricken zones in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Moving swiftly and quietly, Lower united the quills and released the bottom slipknot in each dog. His eyes followed the red path of arterial blood as it streamed through and dripped around the quill. The experiment was working. As he watched with his trademark dispassion, Lower allowed the rivers of blood to flow just “till the [donor] dog began to cry, and faint, and fall into convulsions and at last dye by his side.”

15

Expressionless as ever, the surgeon turned his full attention to the survivor. When the “tragedy was over” he deftly removed the awkward apparatus from the dog's wound and stitched up his patient. Once freed, the dog immediately leaped up from the table, shook himself, and ran away “as if nothing ailed him.” Blood flowed from one dog into another without, it seemed, ill effects on the recipient.

In June 1666 Robert Boyle masked his eagerness with diplomatic reserve as he wrote to Lower, on behalf of the society, for more information about his earlier successes. “[I heard that] you had at lastâ¦successfully accomplished that most difficult experiment on the transference of blood from one to

the other of a pair of dogs.” The “celebrated assembly” wished, Boyle explained, “for a more careful account of the success of the experiment.” In a last effort to persuade Lower to lay bare his secrets, Boyle closed the letter with friendly praise: “There are many among its members who esteem you at your

right worth and [who] are your friends, but none more so than Yours Affectionately, Rob. Boyle.”

16