Blood Work (6 page)

Authors: Holly Tucker

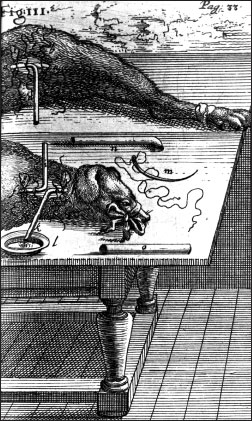

FIGURE 7:

The first animal transfusion experiments were performed on dogs and usually connected the carotid artery to the jugular vein or the carotid artery to the femoral vein. Johann Sigismund Elsholtz,

Clysmatica nova

(1667).

Lower was more than happy to cooperate. His fingers black with ink, he spared no detail as he recounted the canine experiment at length, filling page after manuscript page about his choice of animals, their positioning on the table, the tools he used, the amount of blood that was shed, and of course the meticulous craft required. Lower made it clear to Boyle that he had every intention of continuing his bloody experiments; of that there was no doubt. But he was also eager to see just how far his model might be taken, offering detailed suggestions for those who might wish to try the procedure themselves. He had learned, Lower explained, that a small, weak dog did not make the ideal donor. Its heart beat too faintly, too quickly. “To prevent this trouble, and [to] make the experiment certain,” he wrote, “you must bleed a great dog into a little one, or a mastif into a curr.”

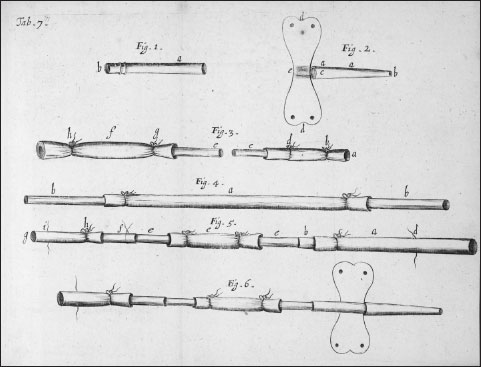

The surgeon's ongoing frustration, though, remained in the tools he used. Plucked from geese, quills were most commonly used for letter writing, not history-making surgical experiments. They were too small, and their qualityâprepared as they were by decidedly unscientific quill dressersâwas not always consistent. Instead of quills, then, Lower suggested that a specially designed “small crooked pipe of silver or brass” be attached to the end of each quill, serving as something of an anchor to a longer, man-made tube. Lower concluded his letter to Boyle by expressing his hopes that his trials would be “prosecuted to the utmost variety the subject will bear.”

17

Â

D

espite Lower's resolve to continue his work, blood transfusion trials would suddenly come to a halt once again when death refused to relinquish its hold on the weakened city. The last shovelfuls of dirt had barely settled on the city's mass

plague graves when a fire, lit in a tiny bakery in Pudding Lane, devoured the heart of the capital on September 2, 1666. Narrow streets, timbered houses, summer drought, and strong eastward winds set ideal conditions for the inferno. Spooked and whinnying horses pulled carts loaded high with desperate refugees and whatever personal belongings they had been able to gather. Clogged streets were brought to a chaotic standstill in the frantic exodus from the city. Some lucky souls were able to make their way to the Thames and onto the overloaded boats that filled the river. The passengers set off directionless, torn between keeping an eye on the red glow of their city and the slowly rising water at their feet. Those who decided not to

brave the frenzied streets remained in their homes, waiting and praying.

18

FIGURE 8:

Richard Lower proposed a system of interconnected brass tubes that could be used in conjunction with quills for his early blood transfusions.

Tractatus de corde

(1669).

The only defense against the searing-hot beast was to admit defeat. King Charles II ordered the lord mayor of London to “spare no houses and pull down the fire every way.”

19

Perfectly intact homes exploded with the help of gunpowder; men with axes and shovels followed behind to clear a protective ring against the conflagration. The preemptive destruction helped to contain the fire, but “containment” was a relative term when more than 13,200 homes and 87 churches had already been incinerated. When the four-day inferno was finally extinguished on September 5, 1666, 85 percent of the buildings within the city's walls were little more than smoldering ashes.

20

Upwards of 65,000 people in this once-vibrant city were now homelessâand wondering when God's fury would end.

21

To make matters worse England was deep in the middle of war. The two-year war between England and Holland that was thought to have been resolved in 1654 warmed up again in February 1665, just months before the plague. The Dutch were joined by the French eleven months later, in January 1666, and there were few signs that a truce was on the horizon. The French king Louis XIV was pleased about the fire's obvious strategic advantage for his country against its enemy. He did, however, prohibit any public rejoicing following the catastrophe and sent word of his willingness to lend aid to Londoners in their time of need. The gesture was greeted with appropriate diplomatic protocol, but there was little chance that the French king's largesse would be accepted.

In the days following the London fire, angry mobs needed to fix blame somewhere, anywhere. They set their sights on Dutch and French Protestants, who had come to England seeking asylum from religious persecution. Rumors spread as fast as the

fire itself that a crazed Dutchman, assisted by the French, had delighted in throwing fireballs into the homes of innocents. The Londoner William Taswell detailed the random acts of violence that filled the streets in the days and weeks after the Great Fire:

A blacksmith in my presence, meeting an innocent Frenchman walking along the street, felled him instantly to the ground with an iron bar. I could not help seeing the innocent blood of this exotic flowing in a plentiful stream down to his ankles. In another place, I saw the incensed populace divesting a French painter of all the goods he had in his shop, and, after having helped him off with many other things, leveling his houseâ¦. My brother told me he saw a Frenchman almost dismembered in Moorfields because he carried balls of fire in a chest with him, when in truth they were only tennis balls.

22

One Frenchmanâreportedly feeble-mindedânonetheless met his fate at the hands of the hangman after he confessed, erroneously and under coercion, to having started the fire in Pudding Lane. The anger of the British against the French was palpable in the shouts and taunts directed at Robert Hubert as he was led through the streets on his way to the gallows late that October. When an anatomist stepped forward to claim Hubert's body, he was shoved aside by the rabid crowd. By the time the masses were done beating and stripping the corpse, there was nothing left to anatomize.

23

Three weeks after the fire the House of Commons appointed a committee of seventy persons to investigate its causes. The committee heard story upon story of “eye-witness” reports that “published with great assurance, came to nothing upon a strict examination.” The committee's report was inconclusive regard

ing foreign involvement in the inferno, and Parliament had no choice but to drop the matter. Charles II and his ministers went even further and declared that “nothing hath been found to argue the fire in London [was] caused by other than the hand of God, a great wind, and a very dry season.”

24

Despite the horrific losses the destruction of London was for some a catastrophicâbut decidedly welcomeâprelude to a glorious rebirth. “Never a calamity, and such a one, was so well bourne as this is,” wrote one observer just a week after the fire. “'Tis incredible, how little the sufferers, though great ones, doe complain of the Losses. I was yesterday in many meetings of the principal Citizens, whose houses are laid in ashes, who instead of complaining, discoursed almost of nothing, but a survey of London and a dessein for rebuilding.”

25

Â

O

nce fascinated by blood circulation and infusion, Christopher Wren scrambled to draw up a new street plan for London over the six days immediately following the fire. Wren's ideas, which he presented to the king and his council on September 11, were clearly influenced by the young man's more recent experiences on the Continent. Now a member of the Royal Society, Wren had only just returned from a memorable trip to Paris. Planned well in advance, Wren's trip to the French capital in the plague-ridden summer of 1665 could not have been better timed. Instead of coming face-to-face with the hideous illness that fell other Londoners, Wren avoided contagion and explored the ever-growing marvels of the city in style.

The English and French capitals were a study in contrasts. While London struggled to survive, Paris nurtured its reputation as the seventeenth century's center of high taste and cutting-edge aesthetics. Wren had been sent to the French capital by Sir John Denham, Surveyor of the King's Works, to observe the

flurry of construction going on there as part of Louis XIV's propagandist efforts to create buildings that were as impressive as the young king intended his reign to be.

26

Hammers and chisels echoed in the Paris air as the monuments that defined the Sun King's reign rose from the ground. Inspired by Saint Peter's, the Church of Val-de-Grâce was nearing completion, a first important step toward what Louis XIV's prime minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, envisioned for Paris as a “new Rome.” Across the river from the Louvre, premier architect Louis Le Vau had been hard at work on the sprawling Collège des Quatre-Nations, with its equally soaring high dome and colonnaded facade. While major additions to the Louvreâhome to French monarchs since the Middle Agesâwere under way, work had also commenced on the remote outskirts of Paris, in Versailles, on a new royal palace. What was once a modest hunting lodge was set for eye-popping grandeur under the expert eye of Le Vau, the painter Charles Le Brun, and the landscape architect André Le Nôtre.

Inspired by what he had just seen in Paris, Wren eagerly got to work and began mapping a new London. While the influences of the neoclassical Italian and French models he had studied on the Continent figured prominently in Wren's ambitious design, his ideas for London's rebuilding also reflected the scientific and cultural attachment to ideas of circulationâboth as medical model and metaphorâin Restoration England. True to his earlier medical inclinations, Wren began his work with a diagnosis. “Having shown in part the deplorable condition of our patient,” he wrote in reference to the city of London, “we are to consult of the cureâ¦. And herein we must imitate the physician, who when he finds a total decay of nature, bends his skill to a palliative to give respite for a better settlement of the estate of the patient.” Wren further justified his plans by evoking one of the most central features of early medicine: the humors. It would be a “shame to the nation”

and a sign of “the ill and untractable Humours of this Age,” he argued, if London were to be rebuilt on its old foundations.

27

Such a comparison between the health, humors, and the physical state of a city and its inhabitants was not at all novel in early Europe. As early as the first century, the celebrated Roman architect Vitruvius emphasized that there was a symbiosis between the human body and ideal architectural forms. In fact the human body was understood as being so perfectly symmetrical and proportionate that it served as a model for classical construction. Leonardo da Vinci himself celebrated the perfection of the human form and the centrality of man within the cosmos in his archetypal drawing of the perfectly proportioned and geometrically balanced “Vitruvian Man.”

Yet for all that had been discovered about the body, there still remained so much to be learned. Natural philosophers and physicians yearned to control the strange and still unknowable mysteries of human physiology. In their attempts to make sense of the inner workings of the human body, they turned to external, man-made creations onto which they could project their developing physiological theories. Natural philosophers tried their hands at constructing animated, soulless life through machinesâboth human and animal.

28

The

Journal des sçavans

, the primary French scientific periodical of the late seventeenth century, included reports of physicians who “composed statues that resembled so well a man in all of its internal parts, with the exception of the rational soul, that it was possible to see everything that took place in our bodies, and this according to the principles of physics.”

29

Their explanations were complicated, but the materials they used to produce these mechanical men were not: Fireplace bellows stood in for lungs, glass jars for skulls, corn grinders for stomachs. Still, the creators of such mechanical men could be true sticklers for detail. One writer

noted that the male “gland [penis] needs to get larger and lengthen,” therefore “some wrinkled and soft [animal] skin” must be used “so it can dilate and shrink easily.”

30