Bloody Crimes (28 page)

W

hile Lincoln lay in state in the Capitol rotunda, Stanton received a telegram from Governor Andrew Curtin of Pennsylvania, regarding Mary Lincoln:

HARRISBURG,

April 20, 1865.

Hon. E. M. STANTON,

Secretary of War:

I am as yet unadvised as to whether Mrs. Lincoln will accompany the remains. In case she does, will you oblige me by presenting my compliments to her, and say that I will of course expect herself and her family to make my house her home during her melancholy sojourn here. May I beg the favor of an answer?

A. G. CURTIN

Governor Curtin did not know Mary Lincoln’s condition. Overwrought, she had still not left her room, or viewed the president’s remains, and had not attended the White House funeral. She had refused almost all visitors, even close associates of the president from Illinois, including Orville Browning, and high officials of her husband’s administration. She had already begun her final mental descent into postwar instability without the president to save her from drifting away.

Stanton replied quickly to Curtin’s inquiry:

WAR DEPARTMENT,

Washington City,

April 20, 1865.

Governor CURTIN,

Harrisburg:

Your kind and considerate message will be immediately communicated to Mrs. Lincoln. By present arrangements neither she nor her sons will accompany the funeral cortege, she being unable to travel at present.

EDWIN M. STANTON,

Secretary of War.

Just nineteen hours before the train was scheduled to leave Washington, Stanton received a request to add Pittsburgh to the route. He replied to this, and all other last-minute requests, “The arrangements already being made cannot be altered…” Stanton did not announce his choice of men to travel on the train with the remains until April 20, the day before they were scheduled to depart. He also released two dramatic and historic documents. Their content could not have been more different. The first was the key order to Assistant Adjutant General Townsend establishing the protocols for the train that would transport the president’s remains. Stanton was a stickler for detail, and the elaborate process he laid out left nothing to chance.

WAR DEPARTMENT,

Washington City,

April 20, 1865.

Bvt. Brig. Gen. E.D. Townsend,

Assistant Adjutant-General, U.S. Army:

SIR: You will observe the following instruction in relation to conveying the remains of the late President Lincoln to Springfield, Ill. Official duties prevent the Secretary of War from gratifying his desire to accompany the remains of the late beloved and distinguished President Abraham Lincoln from Washington to their final resting place at his former home in Springfield, Ill., and therefore Assistant Adjutant-General Townsend is specifically assigned to represent the Secretary of War, and to give all necessary orders in the name of the Secretary as if he were present, and such orders will be obeyed and respected accordingly. The number of general officers designated is nine, in order that at least one general officer may be continually in view of the remains from the time of departure from Washington until their internment.

The following details, in addition to the General Orders, No. 72, will be observed:

1. The State executive will have the general direction of the public honors in each State and furnish additional escort and guards of honor at places where the remains are taken from the hearse car, but subject to the general command of the departmental, division, or district commander.

2. The Adjutant-General will have a discretionary power to change or modify details not conflicting with the general arrangement.

3. The directions of General McCallum in regard to the transportation and whatever may be necessary for safe and appropriate conveyance will be rigorously enforced.

4. The Adjutant-General and the officers in charge are specially enjoined to strict vigilance to see that everything appropriate is done and that the remains of the late illustrious President receive no neglect or indignity.

5. The regulations in respect to the persons to be transported on the funeral train will be rigorously enforced.

6. The Adjutant-General will report by telegraph the arrival and departure at each of the designated cities on the route.

7. The remains, properly escorted, will be removed from the Capitol to the hearse car on the morning of Friday, the 21st, at 6 a. m., so that the train may be ready to start at the designated hour of 8 o’clock, and at each point designated for public honors care will be taken to have them restored to the hearse car in season for starting the train at the designated hour.

8. A disbursing officer of the proper bureau will accompany the cortege to defray the necessary expenses, keeping an exact and detailed account thereof, and also distinguishing the expenses incurred on account of the Congressional committees, so that they may be reimbursed from the proper appropriations.

EDWIN M. STANTON,

Secretary of War.

Stanton did not order Townsend to draft and telegraph back to Washington detailed reports of the funeral ceremonies in each city. Townsend would have his hands full commanding the funeral train, with little time to spare for preparing detailed narratives of all the ceremonies unfolding along the route. It would be enough if he informed the War Department that the train was running on schedule and reported whenever he arrived in or departed from a city. Stanton would rely on other sources, including the journalists traveling on the train, and stories published in the Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York newspapers, for detailed coverage of the obsequies in each city.

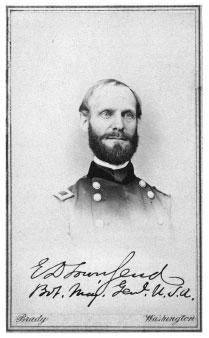

ASSISTANT ADJUTANT GENERAL EDWARD D. TOWNSEND, COMMANDER OF LINCOLN’S FUNERAL TRAIN.

Stanton’s second historic order that day was a public proclamation, signed by him, offering an unprecedented $100,000 reward for the capture of the assassin John Wilkes Booth and of his coconspirators John Surratt and David Herold. Six days after the assassination, the murderer was still at large. And anyone who dared help Booth during his escape from justice would be punished with death. Large broadsides announcing the reward went up on walls all over Washington and New York City.

Jefferson Davis would enjoy his liberty a while longer; he was fortunate that Stanton’s fearsome proclamation did not yet implicate him as an accomplice to Lincoln’s murder or offer a cash reward for his capture. But if Stanton was not prepared to accuse Davis of Abraham Lincoln’s murder, the newspapers were.

O

n the same day that Stanton issued the reward, Davis, writing from Charlotte to General Braxton Bragg, wondered if Lincoln’s murder might help his cause: “Genl. Breckinridge…telegraphs to me, that Presdt. Lincoln was assassinated in the Theatre at Washington…It is difficult to judge of the effect thus to be produced. His successor is a worse man, but has less influence…[I] am not without hope that recent disaster may awake the dormant energy and develop the patriotism which sustained us in the first years of the War.”

Davis busied himself with other military correspondence, including dispatches to General Beauregard on April 20 indicating a scarcity of supplies. “General Duke’s brigade is here without saddles. There are none here or this side of Augusta. Send on to this point 600, or as many as can be had.” In another dispatch Davis asked for cannons and more men, but the replies he received did not indicate that there were any to be sent.

Things were breaking down elsewhere, too. On the evening of April 20, Breckinridge wrote from Salisbury, North Carolina: “We have had great difficulty in reaching this place. The train from Char

lotte which was to have met me here has not arrived. No doubt seized by stragglers to convey them to that point. I have telegraphed commanding officer at Charlotte to send a locomotive and one car without delay. The impressed train should be met before reaching the depot and the ringleaders severely dealt with.”

Davis replied promptly: “Train will start for you at midnight with guard.”

I

n Richmond, Robert E. Lee was at home as a private citizen. He still wore the Confederate uniform and posed in it when Mathew Brady showed up to take his photograph, but he had no army to command. He knew that Davis was still in the field, trying to prolong the war. Lee disagreed with that plan. Any further hostilities must, he believed, degenerate into bloody, lawless, and ultimately futile guerilla warfare. Better an honorable surrender than that. Lee and Davis had enjoyed a good wartime partnership, and he knew the president valued his judgment. On April 20, General Lee composed a remarkable letter to his commander in chief, urging him to surrender.

Mr. President:

The apprehension I expressed during the winter, of the moral condition of the Army of Northern Virginia, have been realized. The operations which occurred while the troops were in the entrenchments in front of Richmond and Petersburg were not marked by the boldness and decision which formerly characterized them. Except in particular instances, they were feeble; and a want of confidence seemed to possess officers and men. This condition, I think, was produced by the state of feeling in the country, and the communications received by the men from their homes, urging their return and the abandonment of the field…I have given these details that Your Excellency might know the state of feeling which existed in the army, and judge of that in the country. From what I have seen and learned, I believe an army cannot be organized or supported in Virginia, and as far as I know the condition of affairs, the country east of the Mississippi is morally and physically unable to maintain the contest unaided with any hope of ultimate success. A partisan war may be continued, and hostilities protracted, causing individual suffering and devastation of the country, but I see no prospect by that means of achieving a separate independence. It is for Your Excellency to decide, should you agree with me in opinion, what is proper to be done. To save useless effusion of blood, I would recommend measures be taken for suspension of hostilities and the restoration of peace.

I am with great respect, yr obdt svt

R. E. Lee

Genl

In the confusion after Appomattox, Davis never received the letter. If he had, its sentiments would have failed to convince him to end the war. Even if Davis had received it, and if he agreed with Lee’s view that resistance east of the Mississippi was futile, he still had faith in a western confederacy on the far side of the Mississippi. Yes, he agreed with Lee on the impropriety of fighting a dishonorable guerilla war. He would not scatter his forces to the hills and sanction further resistance by stealth, ambush, and murder. But Davis, unlike Lee, still believed he could prevail with conventional forces.

Davis and Lee did not communicate again until after the war was over. Indeed, the arrival in Charlotte that very day of several cavalry units gave Davis new hope. According to Mallory:

No other course now seemed open to Mr. Davis but to leave the country, as he had announced his willingness to do, and his immediate advisers urged him to do so with the utmost promptness. Troops began to come into Charlotte, however…and there was much talk among them of crossing the

Mississippi and continuing the war. Portions of Hampton’s, Duke’s, Debrell’s, and Fergusson’s commands of the cavalry were hourly coming in. They seemed determined to get across the river and fight it out, and whenever they encountered Mr. Davis they cheered and sought to encourage him. It was evident that he was greatly affected by the constancy and spirit of these men, and that he became indifferent to his own safety, thinking only of gathering together a body of troops to make head against the foe and so arouse the people to arms.

O

n Friday, April 21—one week after the assassination—Edwin Stanton, Ulysses S. Grant, Gideon Welles, Attorney General James Speed, Postmaster General William Dennison, the Reverend Dr. Gurley, several senators, members of the Illinois delegation, and various army officers arrived at the Capitol at 6:00 a.m. to escort Lincoln’s coffin to the funeral train. Soldiers from the quartermaster general’s department, commanded by General Rucker, the officer who had led the president’s escort from the Petersen house to the White House,