Bloody Crimes (31 page)

PRESIDENT LINCOLN’S HEARSEIN PHILADELPHIA.

Revolution and placed on a platform with his feet pointing north. The entire interior of Independence Hall was shrouded with black cloth. It hung everywhere: from the walls, from the chandelier over the coffin, and from most of the historical oil paintings. The white marble statue of George Washington remained uncovered, and it stood out like a ghost in the blackened room.

Honor guards pulled back the American flag that had covered the coffin during the procession and the undertakers removed the lid to reveal Lincoln’s face and chest. Looming near the president’s head was a monumental metal object, the most renowned and beloved symbol of the American Revolution. They had laid the slain president at the foot of the Liberty Bell. It was a patriotic gesture that stunned the crowd.

On February 22, 1861, ten days before taking the oath of office, president-elect Lincoln told a Philadelphia audience: “I have never had a feeling politically that did not spring from the Declaration of Independence…that which gave promise that in due time the weights should be lifted from the shoulders of all men, and that

all

should have an equal chance…Now, my friends, can this country be

saved upon that basis?…If it can’t be saved upon that principle…if this country cannot be saved without giving up on that principle…I would rather be assassinated on this spot than to surrender it.”

A contemporary writer described the memorial scene:

On the old Independence bell, and near the head of the coffin, rested a large and beautifully made floral anchor, composed of the choicest [japonicas and jet-black] exotics…Four stands, two at the head and two at the foot of the coffin, were draped in black cloth, and contained rich candelabras with burning tapers; and, again, another row of four stands, containing candelabra also, making in all eighteen candelabras and one hundred and eight burning wax tapers.

Between this flood of light, shelving was erected, on which were placed vases filled with japonicas, heliotropes, and other rare flowers. These vases were twenty-five in number.

A delicious perfume stole through every part of the Hall, which, added to the soft yet brilliant light of the wax tapers, the elegant uniforms of the officers on duty, etc., constituted a scene of solemn magnificence seldom witnessed.

Newspaper accounts failed to describe the practical purpose of the sweet-smelling flowers, but they were there for a reason. Lincoln had been dead a week, and the embalmers were fighting a ticking clock. They had slowed but could not stop the decay of his flesh. Fragrant flowers would mask the odor.

Dignitaries viewed Lincoln first, from 10:00 p.m. until midnight. Then the public surged in, entering via temporary stairs through two windows and exiting, via a second set of stairs, through the windows facing Independence Square. The coffin was closed at 2:00 a.m. on Sunday, April 23. Many of those who failed to glimpse the president stood outside Independence Hall for the rest of the night to be sure they would be admitted when the doors reopened in several hours.

Beginning at 6:00 a.m. Sunday, authorities had announced, the public would be admitted until 1:00 a.m. Monday.

By late morning on Sunday, the line of mourners extended as far west as the Schuylkill River and east to the Delaware River. “After a person was in line,” reported the

Philadelphia Inquirer,

“it took from four to five hours before an entrance into the Hall could be effected.” After the long wait, mourners were given only a few seconds to view Lincoln: “Spectators were not allowed to stop by the side of the coffin, but were kept moving on, the great demand on the outside not permitting more than a mere glance at the remains.”

The vast crowds had become dangerous and the

Inquirer

reported alarming incidents: “Never before in the history of our city was such a dense mass of humanity huddled together. Hundreds of persons were seriously injured from being pressed in the mob, and many fainting females were extricated by the police and military and conveyed to places of security. Many women lost their bonnets, while others had nearly every article of clothing torn from their persons.”

O

n that Sunday, April 23, Jefferson Davis and his entourage attended church in Charlotte. The minister’s fire-and-brimstone sermon, which according to Burton Harrison denounced “the folly and wickedness” of Lincoln’s murder, seemed to be aimed at Davis. “I think,” Davis said with a smile, “the preacher directed his remarks at me; and he really seems to fancy that I had something to do with the assassination.” Despite his predicament, the president had not lost his sense of humor.

Later that day, Davis wrote a long, thoughtful letter to Varina that revealed his state of mind twenty-one days since he had left Richmond. Sanguine, less hopeful, more realistic, but not beaten yet, Davis apologized to his beloved companion for taking her on the lifelong journey that had led to this fate.

My Dear Winnie

I have asked Mr. Harrison to go in search of you and to render such assistance as he may…

The dispersion of Lee’s army and the surrender of the remnant which had remained with him destroyed the hopes I entertained when we parted. Had that army held together I am now confident we could have successfully executed the plan which I sketched to you and would have been to-day on the high road to independence…Panic has seized the country…

The loss of arms has been so great that should the spirit of the people rise to the occasion it would not be at this time possible adequately to supply them with the weapons of War…

The issue is one which is very painful for me to meet. On one hand is the long night of oppression which will follow the return of our people to the “Union”; on the other the suffering of the women and children, and courage among the few brave patriots who would still oppose the invader, and who unless the people would rise en masse to sustain them, would struggle but to die in vain.

I think my judgement is undisturbed by any pride of opinion or of place, I have prayed to our heavenly Father to give me wisdom and fortitude equal to the demands of the position in which Providence has placed me. I have sacrificed so much for the cause of the Confederacy that I can measure my ability to make any further sacrifice required, and am assured there is but one to which I am not equal, my Wife and my Children. How are they to be saved from degradation or want…for myself it may be that our Enemy will prefer to banish me, it may be that a devoted band of Cavalry will cling to me and that I can force my way across the Missi. and if nothing can be done there which it will be proper to do, then I can go to Mexico and have the world from which to choose…Dear Wife this is not the fate to which I invited [you] when the future was rose-colored to us both; but I know you will bear it even better than myself and that of us two I alone will ever look back reproachfully on my past career…Farewell my Dear; there may be better things in store for us than are now in view, but my love is all I have to offer and that has the value of a thing long possessed and sure not to be lost. Once more, and with God’s favor for a short time only, farewell—

Your Husband.

B

ack in Philadelphia, the funeral procession left Independence Hall at 1:00 a.m. on Monday, April 24. This escort—the 187th Pennsylvania infantry regiment, city troops, the honor guard, the Perseverance Hose Company, and the Republican Invincibles—was much smaller than the one that welcomed Lincoln to Philadelphia. Despite the late hour, thousands of citizens from every part of the city joined the march. It took three hours, until almost 4:00 a.m., to reach Kensington Station. Townsend kept Stanton up to date: “We start for New York at 4 o’clock [a.m.]. No accident so far. Nothing can exceed the demonstration of affection for Mr. Lincoln. Arrangements most perfect.” The funeral train departed a few minutes later, en route to New York City.

Thousands of people lined the tracks on the journey to New York City. The train encountered large crowds at Bristol, Pennsylvania, and across the New Jersey state line at Morristown. At 5:30 a.m., the train made a brief stop at Trenton before continuing through Princeton, New Brunswick, Rahway, Elizabeth City, and Newark. The train reached Jersey City, New Jersey, at 9:00 a.m. There the presidential car was uncoupled from the train and rolled onto a ferryboat.

As a young man, Lincoln had floated on a flatboat down the Mississippi River to New Orleans; now he was crossing the Hudson River in a flatboat on his way into New York. The ferry landed in Manhattan at the foot of Desbrosses Street. He was back in the city that had

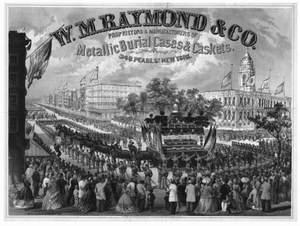

THE EXTRAVAGANT NEW YORK CITY FUNERAL HEARSE. ON THE RIGHT, CITY HALL IS DRAPED IN MOURNING.

helped make him president and that had given him so much trouble during the war.

This was to be the biggest test of the funeral pageant since it had left Washington. New York City had the biggest population, the greatest crowds, and the most volatile citizens in the North. New Yorkers loved a good riot, as they demonstrated on a number of occasions, including the Astor Street Shakespeare riot in the 1840s and, most recently, the Civil War draft riots. Given the strong Copperhead presence in the city, many believed that Manhattan cried crocodile tears for the fallen president. But mourning Unionists outnumbered Lincoln’s enemies on the streets of New York in April 1865.

The procession went from Hudson Street to Canal, to Broadway, and then to City Hall.

The hearse, which was photographed as it rolled through Manhattan, beggared description. According to one published account,

it was fourteen feet long at its longest part, eight feet wide and fifteen feet one inch in height. On the main platform, which was five feet from the ground, was a dais six inches in height, at the corners of which were columns holding a canopy, which, curving inward and upward toward the centre, was surmounted by a miniature temple of liberty. The platform was entirely covered with black cloth, drawn tightly over the body of the car, and reaching to within a few inches of the ground, edged with silver bullion fringe…At the base of each column were three American flags, slightly inclined, festooned, covered with crape. The columns were black, covered with vines of myrtle and camellias. The canopy was of black cloth, drawn tightly, and from the base of the temple another draping of black cloth fell in graceful folds over the first; while from the lower edges of the canopy descended festoons, also of black cloth, caught under small shields. The folds and festoons were richly spangled and trimmed with bullion. At each corner of the canopy was a rich plume of black and white feathers.

The Temple of Liberty was represented as being deserted, having no emblems of any kind in or around it save a small flag on top, at half-mast. The inside of the car was lined with white satin, fluted, and from the centre of the roof was suspended a large gilt eagle, with outspread wings, covered with crape, bearing in its talons a laurel wreath, and the platform around the coffin was strewn with laurel wreaths and flowers of various kinds.

The car was drawn by sixteen gray horses, with coverings of black cloth, trimmed with silver bullion, each led by a colored groom, dressed in the usual habiliments of mourning, with streamers of crape on their hats.

The richness, extravagance, and exaggeration of the sight overwhelmed the senses. New York had outdone all other cities on the

funeral route. To anyone in the streets of Manhattan that day, it seemed unimaginable that any city following New York could rival the magnificence of this day.

One newspaper noted that every public place within sight of the procession was crammed with people: “The police, by strenuous exertions, kept the streets cleared, but the sidewalks and the Park were filled with men, women and children, while the trees in the Park were loaded with adventurous urchins.”

A self-congratulatory

New York Herald

piece swelled with typical Manhattan pride. “The world never witnessed so grand a collection of well-dressed, intelligent, and well-behaved beings, male and female, as thronged the streets of New York yesterday and gathered around the bier of the leader of the nation.”

City Hall had been transformed beyond recognition.

“There was no trace of the interior architecture to be seen on the rotunda of the City Hall,” recalled the main chronicler of the New York funeral.

Niche and dome, balustrade and paneling were all veiled…The catafalque graced the principal entrance to the Governor’s Room. Its form was square, but it was surmounted by a towering gothic arch, from which folds of crape, ornamented by festoons of silver lace and cords and tassels, fell artistically over the curtained pillars which gave form and beauty to the structure.