Bold They Rise: The Space Shuttle Early Years, 1972-1986 (Outward Odyssey: A People's History of S) (19 page)

Authors: David Hitt,Heather R. Smith

Tags: #History

To be sure, Crippen’s background made him an ideal candidate for the position. Crippen had been brought into

NASA

’s astronaut corps in 1969 in a group that had been part of the air force’s astronaut corps. After the cancellation of the air force’s Manned Orbiting Laboratory program,

NASA

agreed to bring most of the air force astronauts who had been involved in the

MOL

program into the

NASA

astronaut corps.

Crippen’s first major responsibility at

NASA

was supporting the Skylab space station program, followed by supporting the shuttle during its development phase. “I guess all that sort of added up, building on my experience. Working on the shuttle, I did primarily the software stuff, computers, which I enjoyed doing. And I think all that, stacked up together, kind of opened up the doors for me to fly. . . . I’m not sure whose decision that was, whether it was John Young’s, George Abbey’s, or who knows, but I’m sure glad they picked me.”

Interestingly, Crippen had been part of the earliest wave of college students who had amazing opportunities open up for them by becoming savvy in the world of computer technology. During his senior year he took the first computer programming class ever offered at the University of Texas. “Computers were just starting to—shows you how old I am—to be widely used. . . . Not

PC

s or anything like that, but big mainframe kind of things, and Texas offered a course, and I decided I was interested in that and I would try it. It was fun. That was back when we were doing punch cards and all that kind of stuff.”

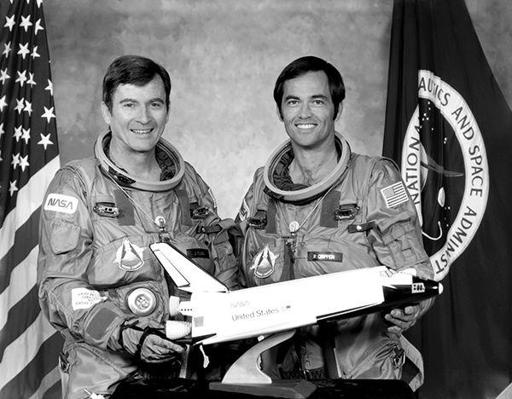

13.

STS

-1 crew members Commander John Young and Pilot Bob Crippen. Courtesy

NASA

.

With that educational background under his belt, Crippen took advantage of an opportunity with the air force Manned Orbiting Laboratory program to work on the computers for that vehicle. That in turn carried over, after his move to

NASA

, to working on computers for Skylab, which were similar to the ones for

MOL

.

“It was kind of natural, when we finished up Skylab and I started working on the Space Shuttle, to say, ‘Hey, I’d like to work on the computers,’” Crippen said. “T. K. Mattingly was running all the shuttle operations in the Astronaut Office at that time and didn’t have that many people that wanted to work on computers, so he said, ‘Go ahead.’ . . . The computer sort of interfaced with everything, so it gives you an opportunity to learn the entire vehicle.”

Of course, being named pilot for

STS

-1 didn’t mean that Crippen would actually pilot the vehicle. “We use the terms ‘commander’ and ‘pilot’ to confuse everybody, and it’s really because none of us red-hot test pilots want to be called a copilot. In reality, the commander is the pilot, and the pilot

is a copilot, kind of like a first officer if you’re flying on a commercial airliner. [My job on

STS

-1] was primarily systems oriented, working the computers, working the electrical systems, working the auxiliary power units, doing the payload bay doors.”

Crippen considered it an honor to work with the senior active member of the Astronaut Office for the flight. “When you’re a rookie going on a test flight like this, you want to go with an old pro, and John was our old pro,” he said.

He had four previous flights, including going to the moon, and John is not only an excellent pilot, he’s an excellent engineer. I learned early on that if John was worried about something, I should be worried about it as well. This was primarily applying to things that we were looking into preflight. It’s important for the commander to sort of set the tone for the rest of the crew as to what you ought to focus on, what you ought to worry about, and what you shouldn’t worry about. I think that’s the main thing I got out of John.

Crippen described Young as one of the funniest men he ever knew and regretted that he didn’t keep record of all the funny things Young would say. “He’s got a dry wit that a lot of people don’t appreciate fully at first,” Crippen said, “but he has got so many one-liners. If I had just kept a log of all of John’s one-liners during those three years of training, I could have published a book, and he and I could have retired a long time ago. He really is a great guy.”

The crew was ready; the vehicle less so. There were delays, followed by delays, followed by delays. Recalled astronaut Bo Bobko, “John Young had come up to me one day and said, ‘Bo,’ he said, ‘I’d like you to take a group of guys and go down to the Cape and kind of help get everything ready down there.’ And he said, ‘I know it’s probably going to take a couple of months.’ Well, it took two years.”

Much of that two years was waiting for things beyond his control, things taking place all over the country, Bobko said. However, he said, even the time spent waiting was productive time. He and others in the corps participated in the development and the testing that were going on at the Cape. Said Bobko,

Give you an example. I gave Dick Scobee the honor of powering up the shuttle the first time. I think it was an eight o’clock call to stations and a ten o’clock test start in the morning. I came in the next morning to relieve him at six, and he wouldn’t leave until he had thrown at least one switch. They had been discussing the procedures and writing deviations and all that sort of thing the whole day before and the whole night, and so they hadn’t thrown one switch yet. So there was a big learning curve that we went through.

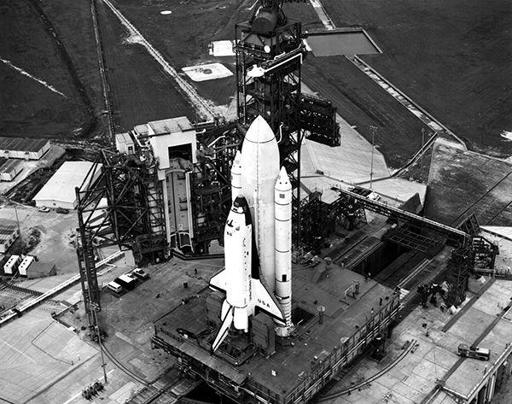

14.

Space Shuttle

Columbia

arrives at Launchpad 39

A

on 29 December 1980. Courtesy

NASA

.

Finally, the ship was ready.

Launch day came on 10 April 1981. Came, and went, without a launch. The launch was scrubbed because of a synchronization error in the orbiter’s computer systems. “The vehicle is so complicated, I fully anticipated that we would go through many, many countdowns before we ever got off,” Crippen recalled. “When it came down to this particular computer problem, though, I was really surprised, because that was the area I was supposed to know, and I had never seen this happen; never heard of it happening.”

Young and Crippen were strapped in the vehicle, lying on their backs, for a total of six hours. “We climbed out, and I said, ‘Well, this is liable to take months to get corrected,’ because I didn’t know what it was. I’d never seen it,” Crippen said. “It was so unusual and the software so critical to us. But we had, again, a number of people that were working very diligently on it.”

The problem was being addressed in the Shuttle Avionics Integration Laboratory, which was used to test the flight software of every Space Shuttle flight before the software was actually loaded onto the vehicle. Astronaut Mike Hawley was one of many who were working on solving the problem and getting the first shuttle launch underway. “We at

SAIL

had the job of trying to replicate what had happened on the orbiter, and I was assigned to that,” Hawley explained. “What happened when they activated the backup flight software, . . . it wasn’t talking properly with the primary software, and everybody assumed initially that there was a problem with the backup software. But it wasn’t. It was actually a problem with the primary software.”

When the software activates, he explained, it captures the time reference from the Pulse Coded Modulation Master Unit. On rare occasions, that can happen in a way that results in a slightly different time base than the one that gets loaded with the backup software. If they don’t have the same time base, they won’t work together properly, and that was what had happened in this case.

So what we had to do was to load the computers over and over and over again to see if we could find out whether we could hit this timing window where the software would grab the wrong time and wouldn’t talk to the backup. I don’t remember the number. It was like 150 times we did it, and then we finally re-created the problem, and we were able to confirm that. So that was nice, because that meant the fix was all you had to do was reload it and just bring it up again. It’s now like doing the old control-alt-delete on your

PC

. It reboots and then everything’s okay. And that’s what they did.

Crippen said

SAIL

concluded that the odds of that same problem occurring again were very slim. This was all sorted out in just one day. “We scrubbed on the tenth, pretty much figured out the problem on the eleventh, and elected to go again on the twelfth.”

Crippen, though, had little faith that the launch would really go on the twelfth. “I thought, ‘Hey, we’ll go out. Something else will go wrong. So we’re going to get lots of exercises at climbing in and out.’ But I was wrong again.”

On 12 April 1981 the crew boarded the vehicle, which in photos looks distinctive today for its white external tank. The white paint was intended to protect the tank from ultraviolet radiation, but it was later determined that the benefits were negligible and the paint was just adding extra weight.

After the second shuttle flight, the paint was no longer used. Doing without it improved the shuttle’s payload capacity by six hundred pounds.

Strapped into the vehicle, the crew began waiting. And then waiting a little bit more. “George Page, a great friend, one of the best launch directors Kennedy Space Center has ever had, really ran a tight control room,” Crippen recalled. “He didn’t allow a bunch of talking going on. He wanted people to focus on their job. In talking prior to going out there, George told John and I, he says, ‘Hey, I want to make sure everybody’s really doing the right thing and focused going into flight. So I may end up putting a hold in that is not required, but just to get everybody calmed down and making sure that they’re focused.’ It turned out that he did that.”

Even after that hold, as the clock continued to tick down, Crippen said, he still was convinced that a problem was going to arise that would delay the launch.

It’s after you pass that point that things really start to come up in the vehicle, and you are looking at more systems, and I said, “Hey, we’re going to find something that’s going to cause us to scrub again.” So I wasn’t very confident that we were going to go. But we hadn’t run into any problem up to that point, and when . . . I started up the

APU

s, the auxiliary power units, everything was going good. The weather was looking good. About one minute to go, I turned to John. I said, “I think we might really do it,” and about that time, my heart rate started to go up. . . . We were being recorded, and it was up to about 130. John’s was down about 90. He said he was just too old for his to go any faster. And sure enough, the count came on down, and the main engines started. The solid rockets went off, and away we went.

Astronaut Loren Shriver had helped strap the crew members into their seats for launch and then left the pad to find a place to watch. He viewed the event from a roadblock three miles away, the closest point anyone was allowed to be for the launch, where fire trucks waited in case they were needed. “I remember when the thing lifted off, there were a number of things about that first liftoff that truly amazed me,” he said.

One was just the magnitude of steam and clouds, vapor that was being produced by the main engines, the exhaust hitting the sound suppression water, and then the solid rocket boosters were just something else, of course. And then when the sound finally hits you from three miles away, it’s just mind-boggling. Even for an experienced fighter pilot, test pilot, it was just amazing to stand through that, because being that close and being on top of the fire truck . . . the pressure waves are basically unattenuated except by that three miles of distance. But when it hits your chest, and it was flapping the flight suit against my leg, and it was vibrating, you could feel your legs and your knees buckling a little bit, could feel it in your chest, and I said, “Hmm, this is pretty powerful stuff here.”