Boost Your Brain (29 page)

Authors: Majid Fotuhi

What’s Going On in the Brain?

In the short term, insufficient sleep triggers your sympathetic nervous system, which, as you’ll read in

chapter 10

, has an immediate effect on your brain function. Cortisol, released during this response, heightens awareness—it’s part of the fight-or-flight response you need to respond to emergencies. But the brain on excess cortisol isn’t as accurate in solving complicated problems, making it more likely that you’ll make mistakes in the heat of the moment. High cortisol can also affect your brain wave activity—insomnia patients have higher levels of excessively fast beta activity, a sign of hyperarousal in the brain.

16

In the long term, poor or inadequate sleep has a direct effect on the structure of the brain. Animal studies have shown that sleep deprivation is tied to a smaller hippocampus, and one study of thirty-six men showed the same effect in humans.

17

There’s evidence, too, that the increase in cortisol that accompanies insufficient sleep inhibits neurogenesis in the hippocampus.

18

Insufficient sleep also affects brain structure and health indirectly. Regularly getting fewer than six hours of sleep a night is associated with chronic pain, hypertension, and inflammation, all of which may affect the brain. And researchers at the University of Alabama at Birmingham concluded that fewer than six hours of sleep a night significantly increases the risk of stroke for people who aren’t overweight or obese and don’t have OSA.

19

Shorting yourself on sleep also may raise your risk of obesity, a brain shrinker you’ll read about in

chapter 11

. And obesity, as you know, increases the risk of OSA. In fact, between 30 and 40 percent of my patients have both sleep apnea and insomnia, a double whammy for the brain. Insomnia is also one of the chief diagnostic features of depression, which takes its own toll on the brain and on patients’ lives.

Brain function, not surprisingly, takes a hit from prolonged sleep problems. In one study of more than fifteen thousand nurses over the age of seventy, those who had fewer than five hours of sleep per night over a six-year period did worse on cognitive assessments than those who slept an average of seven hours a night.

20

The Sleep–Food Link

Poor sleep may be affecting you in another way that shrinks the brain: lowering your resistance to foods you might otherwise chose to avoid. In one study conducted by researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, healthy adults deprived of sleep for a night were more likely to experience heightened desire when shown a food item than they were after having a full night’s sleep. Functional MRIs of the twenty-three subjects who were sleep deprived also showed decreased activation in the frontal lobes—the brain’s braking system—just the place they’d need to recruit to make healthy food choices.

In another study, researchers found that a single night without sleep resulted in increased feelings of hunger in twelve healthy young men.

21

In addition, when viewing images of food, the men showed greater activation in the right anterior cingulate cortex, an area of the brain tied to desire and craving. Activation here might explain their urge to eat.

Getting Better: Reversing the Damage of Sleep Disorders

If you’re worried about your snoring, or the late nights and early mornings that are your current way of life, that’s probably a good thing. OSA and insomnia are major brain shrinkers. Stopping further damage as soon as possible is critical to ensuring your brain functions at its peak, now and in the future. This is so critical, in fact, that I recommend sleep apnea screening for anyone over the age of fifty who snores. I think it is as important—if not more so!—than getting a colonoscopy or mammogram at this age. Doctors should routinely include questions about sleep problems in the evaluations of their patients.

If you have OSA or insomnia, you should make a commitment to starting treatment immediately, and sticking with it.

Patients with OSA should avoid drinking alcohol at night and taking sedating medications; these can worsen OSA. They should also be vigilant about reducing their other stroke risk factors, since having OSA ups their risk of stroke. The good news is that OSA can be very effectively treated with a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) device, which blows air into your nose while you sleep, keeping your airway open. Often, after a few days using CPAP, patients report feeling better than they have in years. Other treatments include mouth appliances that keep the airway open, surgery (for anatomical causes of OSA), and conservative treatments like sleeping on your side. There are also medications that can help to reduce daytime sleepiness in patients. I usually give a short trial of modafinil to my patients for a few days to see if they improve. If they do, they can take it regularly. Many times OSA also resolves completely with weight loss.

And there’s more good news: as terrible as sleep disorders are for the brain, much of the damage they cause seems to be reversible. The results can be stunning. Remember the brain-shrinking effects of OSA reported by the Italian research team? Their research was actually aimed not just at measuring the impact of OSA, but also at testing the theory that treatment of OSA would result in significant improvements in brain structure and performance on cognitive tests.

After initial testing of the study subjects, Castronovo and her team treated the patients with CPAP for three months and then tested and imaged them again. With three months of treatment, fMRIs of OSA patients—which, remember, had shown them to be working overtime to complete cognitive tasks—now looked very similar to those of non-OSA study subjects. Treated OSA patients also did better on cognitive tasks and showed an increase in the size of the hippocampus and frontal lobes compared to before treatments. White matter in OSA patients had also largely normalized. If you’re not already amazed by the incredible plasticity of the human brain, this alone will surely convince you.

More study is needed, but it seems there is hope that just as the lungs recover over a period of years after a person stops pumping them with cigarette smoke, so too the brain recovers and rejuvenates once the brain-draining effects of sleep apnea are eliminated.

In children, at least, this seems to be true. Children who had sleep apnea caused by large adenoids or tonsils, for example, had poor sleep quality and did poorly on cognitive tests compared to a non-sleep-apnea control group. But their BDNF levels, sleep quality, and cognitive abilities all had risen six months after having surgery to eliminate the cause of sleep apnea.

22

After twelve months BDNF levels, sleep quality, and cognitive abilities were no different in the children who once had sleep apnea than they were in the children who’d never had it.

The brain-draining effects of insomnia likely aren’t indelibly etched either. In one animal study, for example, two weeks of treatment with a sleep aid resulted in a 46 percent greater survival of newborn hippocampal neurons.

23

That’s not necessarily a prescription for success, however. I usually use sleep aids as a last resort or a temporary measure for my insomnia patients since medications can be habit forming and long-term use can be associated with increased risk of cognitive impairment with aging. Therefore, I encourage my patients to gear their efforts toward eliminating the root causes of insomnia and incorporating brain-boosting activities into their lives. If work stress is keeping you up at night, for example, using the ABC method outlined in

chapter 6

may help you reduce your anxiety so you can slumber soundly. Meditation and exercise (but not right before bed) should also improve your sleep.

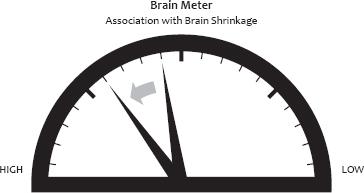

Untreated sleep problems, especially obstructive sleep apnea, are associated with significant risk for strokes, along with brain atrophy. The worse your sleep disorder, the more your brain will shrink.

Cashing In Your Sleep IOU

If you make a habit of giving short shrift to your sleep, it’s tempting to think you can “catch up” with a marathon snooze session once whatever is keeping you up has passed. But can you really?

Scientists don’t yet have a solid answer, says Dr. Emsellem, but it looks likely that “catching up” on sleep may not be as simple as you think. Reversing the effects of a serious sleep debt “may take as much as four to six weeks of sustained sleep to really balance out and catch back up,” she warns.

How Stress or Depression May Be Shrinking Your Brain

Y

OU’VE BEEN

working on the proposal for months, staying late at work, and eschewing weekend downtime in favor of long hours at your computer. If you nail this presentation, your company stands a good chance of winning a key contract and avoiding layoffs, including—quite likely—your own. You know you’ve done a bang-up job, but as presentation time approaches, the pressure is on. And, honestly, you’re not exactly feeling in peak mental shape.

In fact, you’re beginning to feel like you’re losing your marbles. Case in point: you just spent twenty minutes looking for the printout you’d had in your hand but then absentmindedly laid down (on top of the filing cabinet, as it turns out). And you’d left the office for a quick bout of errand running but then forgot to make two essential stops. At home, you’ve been forgetful and fuzzy. Are you just imagining things or has your formerly reliable brain gone haywire—just when you need it most?

Chances are you really are experiencing slower thinking and increased forgetfulness. And there’s a perfectly good explanation: stress changes the brain—subtly with small doses; more dramatically with prolonged or extreme stress; perhaps most dramatically of all with chronic, major depression. Prolonged excess stress, we now know, causes the parts of the brain responsible for memory, attention, and decision making to shrink.

Too much stress can tip some people into depression, which also shrinks the brain. If you’re feeling a little tense just thinking about this, take a deep breath. The damage caused by stress and depression is reversible. We’ll get to that, but first you’ll need to understand just how stress damages your brain.

(A Little) Stress Is Good

As you probably know, you’re equipped with a rather handy stress-response system, which is often referred to as your fight-or-flight response. In fight-or-flight mode, your sympathetic nervous system releases hormones, including cortisol, which works with adrenaline to increase blood flow to your heart and other muscles throughout your body, and to heighten your awareness. In other words, it prepares you to either defend yourself (fight) or run (flight).

This emergency response system is designed to work for as long as it takes you to reach safety—from mere seconds to hours. When the emergency has passed, your parasympathetic nervous system releases hormones that counteract those released in fight-or-flight mode and your body and brain return to a normal state. Your heart rate slows; your muscles relax.

Being exposed to some stress can be helpful—and not just when you’re trapped in a burning building or staring down a predator. In fact, mild, “acute,” or short-term stress actually heightens your attention and focus. Consider the stress you feel when you sit down to take an exam or be interviewed for a job. Most likely it’s just powerful enough to help you focus on the task at hand—and do your best. This is the fight-or-flight mechanism working as intended, giving you just enough energy and focus to perform at your peak.

To Stress or Not to Stress?

You probably know someone who becomes irate when stuck in traffic. Or who breaks into a cold sweat at the thought of speaking to a large group of people. We all respond to perceived stressors in different ways. Just how we handle them depends on a variety of factors, including some of our earliest life experiences. We know this, in part, thanks to the research of McGill University professor Michael Meaney, an expert on stress and the brain, whom I worked with when I was an undergraduate student. It was working with Dr. Meaney, in fact, that sparked my long-lasting interest in how stress affects the brain.

One of Dr. Meaney’s best-known studies looked at what happened to infant animals who were cared for—or neglected—by their mothers. As it turned out, baby animals groomed by their mothers experienced changes in their brains that made them better able to handle stress later in life. Animals who were denied maternal care early in life, on the other hand, were less able to handle stress once they reached adulthood. Early life experiences affected their stress response later in life.