BOSS TWEED: The Corrupt Pol who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York (57 page)

Read BOSS TWEED: The Corrupt Pol who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York Online

Authors: Kenneth D. Ackerman

Tags: #History

Thomas Nast emerged from the Tweed affair as the most celebrated graphic artist of his time. His influence already had been profound, establishing the political cartoon as a powerful voice and building a language of symbols still ubiquitous: Uncle Sam, the Democratic donkey, the Republican elephant, and our modern Santa Claus. For twenty years after Tweed, he wielded his pencil as a scimitar over American politics. Presidents and senators dreaded his lampoons, and his friendship could tilt national contests. Success made him rich. By the early 1880s, Nast had accumulated a small fortune of $125,000, enormous for a newsman.

Harper’s Weekly

paid him an annual retainer of $5,000 plus hundreds more per drawing. He earned a total of $25,000 in 1879 alone, more than triple the $7,500 salary then paid to United States Senators and more than double the $10,000 paid to the vice president and cabinet members.

But Nast, perhaps because he’d enjoyed so much success so early, failed to change with his times. Competitors cropped up like Joseph Keppler’s satirical weekly

Puck,

The Judge

magazine, and the

Daily Graphic

that began to win away his audience. He adapted poorly to new technology:

Harper’s Weekly

in 1880 changed its method for turning artwork into typeset, switching from the hand-engraving of wooden blocks to photochemical reproduction. For Nast, this meant abandoning the soft pencils he’d used for years and turning to ink pens that gave him a thinner, weaker line. At the same time,

Harper’s Weekly

began playing down its pure political content to reach a broader family audience. Unthinkably, in the early 1880s, it began rejecting many of Nast’s drawings.

Nast had quit the magazine briefly in 1877 in an argument over editorial policy; he left for good in 1886. Without steady income, his saving eroded. He lost $30,000 in a single shot by investing in a new Wall Street firm called Grant and Ward, headed by his longtime hero General Ulysses S. Grant; the firm collapsed in 1884 when the junior partner, Ferdinand Ward, turned out to be an embezzler. After that, Nast mortgaged his home in 1893 to start his own new illustrated journal,

Nast’s Weekly

, which failed in the marketplace, losing him thousands more.

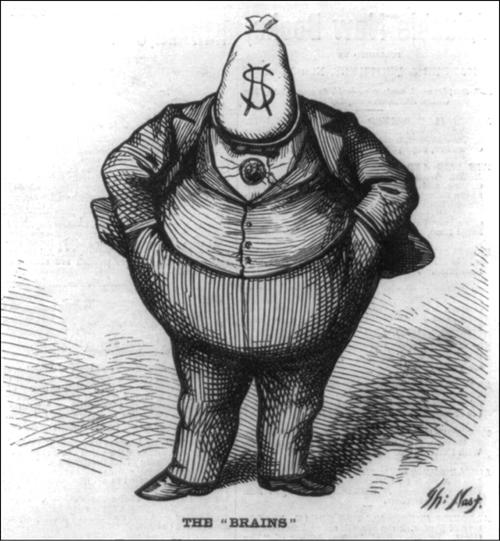

The lasting image of Tweed as money-grabbing pol, created by Thomas Nast.

Harper’s Weekly, October 21, 1871.

Theodore Roosevelt, a lifelong fan, jumped at the chance to help the struggling artist when Roosevelt became president in 1901. He offered Nast a political appointment—American consul to Equador, the only overseas spot then readily open. Nast, loathe to travel but strapped for cash, accepted. Asked by friends what he planned to do in his far-off post at Guayaquel, he quipped, “I am going there to find out how to pronounce the name of it.”

31

Four months after arriving in mid-1902, he died there of yellow fever at 62 years old.

And what of Tweed, the old man who’d once ruled the city as Tammany Grand Sachem only to die behind bars at Ludlow Street Jail? More than a century later, Tweed remains part of the American political vernacular, but usually just as a cartoon character, the image framed by Nast and the

New-York Times

: the fat, corrupt, arrogant political Boss who stole a fortune from the public and defied them by saying “What are you going to do about it?”

Tweed didn’t invent civic corruption or ballot box stuffing, but he and his Tammany crowd elevated the techniques to stunning proportions. They committed frauds gigantic on any scale, even if Tweed was personally guilty for only a small fraction of the while. In later years, estimates of “Tweed Ring” total plunder jumped from the relatively-modest $25 million to $45 million range of the 1877 Aldermen’s Committee to fully $200 million (at least $4 billion in modern dollars), a figure clearly inflated for dramatic impact but never scrutinized. It became part of the legend.

32

Tweed lived in a corrupt time, the Gilded Age, but he defined that era and pressed its boundaries. Even by his own day’s standards, to call something “A Worse Fraud than Tweed’s” spoke volumes.

33

Tweed inherited a culture of graft endemic to New York City for generations and pushed it to its logical extreme, forcing the reformers to crack down. After his excesses, no city in America could tolerate his style of wide-open graft or ballot box abuse. Urban corruption didn’t disappear but it evolved and became more subtle. “A villain of more brains would have had a modest dwelling and would have guzzled in secret,” E.L. Godkin wrote in the aftermath.

34

George W. Plunkett, a Tammany leader of the next generation, well understood the point. “The politician who steals is worse than a thief,” he’d say in 1905. “He is a fool.”

35

It’s hard not to admire the skill behind Tweed’s system, though. The Tweed Ring at its height was an engineering marvel, strong and solid, strategically deployed to control key power points: the courts, the legislature, the treasury, and the ballot box. Its frauds had a grandeur of scale and an elegance of structure: money laundering, profit sharing, and organization. It took the brilliance of a Samuel Tilden just to unravel the basic cash flow.

So sturdy was the frame that even after the

New-York Times

had printed its disclosures and citizens had mobilized, Tweed remained entrenched. The Ring had only one fatal flaw: its humanity. Human beings composed it, governed by greed, vanity, and fear. Greed ultimately took control; they stole too much and lost their nerve. Treachery broke the Ring more than any outside force: Had Jimmy O’Brien not leaked the Secret Accounts, had Judge George Barnard not handed the reformers their pivotal injunction, had Slippery Dick Connolly not handed the Comptroller’s Office over to Tilden and Andrew Green, had Tweed himself shown better leadership and insisted his gang stick together in the crisis, it’s easy to envision their weathering the storm and walking away.

36

At its foundation, Tweed’s system had an irresistible political equation: Everyone benefited, rich and poor alike, and nobody seemed to get hurt. Money for graft as well as good came mostly from outsiders. Taxes stayed low; Connolly financed city operations mostly with debt, selling bonds and stock to investors in Europe and on Wall Street, pushing off payment until another day.

For the wealthy, Tweed produced dynamism and growth. His regime spent $10.4 million on Central Park up through 1869 and millions afterward. Wasteful and riddled with graft? Certainly. But during this time the value of real estate in the three surrounding wards more than tripled, from $26.4 million to over $80 million between 1856 and 1866 generating millions in tax revenue, and the total value of property in the city rose 82.5 percent in the decade form 1860 to 1870—a product of many forces totally beyond Tweed or Tammany, but Tweed’s fingerprints cannot be ignored.

37

Along with growth came a dose of city pride, grand projects like the Brooklyn Bridge, paved uptown streets, and the new Courthouse. Even Andrew Garvey, the plasterer, in describing how he squeezed millions in graft from city projects, reminded investigators: “Mr. Tweed has frequently told me to try to have the work done well.”

38

By contrast, in the mid-1870s with Tweed disgraced and the local economy crippled by the panic of 1873, this frenzied building came to a halt. William Havemeyer, the new mayor, refinanced the city’s debt and restored credit, but he saw only waste and graft in Tweed’s public works. Hundreds of men who dug quarries, leveled streets, and hauled boulders lost their jobs. Havemeyer threatened to halt funding even for the Brooklyn Bridge, turning frugality into a moral stance against “large and centralized schemes of local government.”

39

Andrew Green as comptroller cut every spending request that reached his desk during this period. After a decade of Tweed excess, citizens no longer trusted their money in the hands of activist government.

For the down and out, Tweed offered even more. The marriage of Tammany to the immigrant Irish poor had a pragmatic root. Tweed viewed the immigrants not as charity cases to pity, judge, or befriend. Instead, he respected them as voters to bargain with, to woo and court. He won their loyalty by providing tangible service when government “safety net” programs barely existed. His aid took many forms: state money for schools and hospitals, lumps of coal at Christmas, and city patronage jobs to put bread on family dinner tables. If winning their votes meant getting public aid for Catholic Church schools, Tweed was happy to lead the charge in the legislature, enjoy the credit, and take the political heat.

To Tweed, helping out poor greenhorns had less to do with kindness than politics, a more durable force. By welcoming the newcomers under its wigwam, Tammany gave them a share of power and a sense of community. To be a “Tweed repeater”—a foot soldier in Tammany’s army to steal elections—was a bragging right to many, a badge of belonging and often the ticket to a job. Tweed was no Robin Hood. He stole, but not just from the rich, and he kept a large cut for himself. Still, compared with anyone else, the poor saw it as a pretty good deal.

Critics sneered at this appeal to the city’s “lower stratum.” Many elite politicians of the Victorian age cringed at the concept of popular sovereignty: allowing the unwashed, ignorant masses to outvote respectable taxpayers. They threw up their hands at “ruling vast bodies of human beings, containing a large percentage of the vicious, the ignorant, the criminal, and the unfortunate,” as journalist Charles Wingate put it.

40

Tweed rejected this. He’d proved the city could be governed even after the maelstrom of the Civil War draft riots, though he’d clearly lost his touch by the time of his own scandals.

The problem was, Tweed’s system was based on lies. Stealing was wrong, even then, and Tweed and the others knew it perfectly well. No regime based on it could last, or deserved to last. Eventually, the bills came due, the creditors got nervous, and the house of cards collapsed. Meanwhile, democracy itself almost drowned in the process: self-government meant little when elections were won by the side that cheated best. Tweed’s style of running a political party—rigorous organization, ethnic inclusion, and tough discipline—became staples of big city machines for a century, fitting the lofty theories of democratic government to the rough realities of life. But with it came a dark-edged tradition: corruption on one side and overbearing celebrity prosecutors on the other.

The man behind the image can only be appreciated as a mass of contradictions. “Tweed was a bold, bad, able man, who had far higher ambition, far higher skill, [and] played with great recklessness the very game which carries other men … to the senatorships, chief-justiceships and governorships, and gives them the petites entrees at the White House,” E.L. Godkin wrote of him at the time.

41

As a politician, Tweed had a human touch others could only envy. Stories abounded of his good nature. Firemen spoke of how he carried ladders through snowstorms to save a burning building or how he enjoyed a good fistfight with a rival squad: “Why, bless you, I’ve seen him wade [into a brawl] alone with a trumpet and clean out a whole hook and ladder company who tried to keep ahead of us in the car track,” one told reporters.

42

Locked away in jail, Tweed found a good word ever for the reporters who’d put him there: “If I could have bought newspapermen as easily as I did members of the Legislature, I wouldn’t be in the fix I am now,” he told the

Brooklyn Eagle

‘s William Hudson. “The most of those—‘cusses would refuse money when they didn’t have enough to get ‘em a decent meal.”

43

He did everything on a grand scale and left a trail of clashing images: The outgoing, backslapping leader uniting the city and helping the poor; the conniving schemer lining his pocket and monopolizing power; the victim of politically-driven prosecutors; the guilty architect of the largest municipal fraud in history. Tweed proudly insisted he had always kept his word, even while fixing a vote or skimming a contract. In the end, even after his epic crimes became public knowledge, people respected his integrity, especially in facing his accusers, serving time in jail, and, in the end, in confessing his guilt. It made him an oddly moral man for the most outrageous thief of his generation.

A century later, the fog has barely lifted. Professor Leo Hershkowitz, after studying Tweed’s court records and municipal archives as closely as anyone, could conclude that Tweed was hardly a criminal at all and had been framed by slanted newspapers and prosecutors: “Tweed’s testimony, his confession, his lack of facts and figures, his altogether pitiful figure suggest he was indeed a paper tiger, a bench warmer, watching the pros at work,” he wrote.

44

On the other side sit the two closest things to smoking guns painting him the master swindler: Samuel Tilden’s chart tracing $1 million in county Tax Levy payouts directly to Tweed’s account at the Broadway Bank, and Tweed’s own confession to the city aldermen.

“Tweedism” didn’t die with Tweed. Tammany Hall would bounce back and remain a power in New York City politics for another ninety years, well into the 1960s. A parade of strong leaders starting with “Honest John” Kelly would clean house and restore discipline.

45

In the twentieth century, Tammany would spawn progressive leaders like Alfred E. Smith who would transform its traditional immigrant roots into an agenda of social legislation at the foundation of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal. But for every Al Smith, Tammany would create a score of crafty fixers like wisecracking Mayor “Jimmy” Walker (1926-1932), popular for defending the nickel subway fare and pushing to legalize Sunday baseball but who resigned under fire over corruption charges and bad publicity from his high-profile extramarital affair with actress Betty Compton.

In 1927, Tammany would leave the old wigwam Tweed had built for it on 14th Street, its home for sixty years, and move to a new home on 17th Street across Union Square.

F

OOTNOTE

The 1930s would see a decline. Fiorello La Guardia (1935-1945), elected mayor in 1934 on a Fusion-Republican ticket, would cut off Tammany from its traditional City Hall patronage. By 1943, Tammany would have to sell its Union Square building and move into rented space at 331 Madison Avenue. That year, the New York County Democratic Committee would cut its formal tie to the club, though the label “Tammany Hall” would stick for another two decades.