Brain on Fire (20 page)

Authors: Susannah Cahalan

“Hello,” my mother said cheerily, entering the room. She propped her leather bag on the chair by the bed and kissed me. “I’m so excited to finally meet the mysterious Dr. Najjar today. What do you think he’ll be like?” she continued brightly, enthusiasm radiating from her almond-shaped eyes. “He should be here any moment.”

Enthusiasm was hard for my dad this morning. “I don’t know, Rhona,” he said. “We don’t know anything yet.”

She shrugged him off and grabbed a tissue to wipe the drool pooling on the side of my face.

“Hello, hello!” A few minutes later, Dr. Najjar strode into my private room, 1276, his voice booming. He had a measured gait and

a slight slope to his back that made his head fall a few inches in front of his body, most likely due to the hours he spent hunched over a microscope. His thick mustache was worn at the tips from his habit of twisting and pulling at it when he was deep in thought.

He extended his hand to my mother, who, in her eagerness, held it firmly a bit longer than normal. Then he introduced himself to my father, who rose to greet him from the chair by my bed.

“Let’s go through her medical history with you before I begin,” he said. His Syrian accent hopped rhythmically, sticking on and accentuating the hard consonants, often turning t’s into d’s. When he got excited, he dropped prepositions and combined words, as if his speech could not keep up with his thoughts. Dr. Najjar always stressed the importance of getting a full health history from his patients. (“You have to look backward to see the future,” he often said to his residents.) As my parents spoke, he took note of symptoms—headaches, bedbug scare, flulike symptoms, numbness, and the increased heart rate—that the other doctors had not explored, at least not in one full picture. He jotted these all down as key findings. And then he did something none of the other doctors had done: Dr. Najjar redirected his attention and spoke directly to me, as if I was his friend instead of his patient.

One of the remarkable things about Dr. Najjar was his very personal, heartfelt bedside manner. He had an intense sympathy for the weak and powerless, which, as he told me later, came from his own experiences as a little boy growing up in Damascus, Syria. He had done poorly in school, and his parents and teachers had considered him lazy. When he was ten, after he failed test after test in his private Catholic school, his principal had told his parents that he was beyond help: “Education is not for everyone. Maybe it would be best for him to learn a trade.” Angry as he was, his father didn’t want to stop his schooling—education was far too important—so although he didn’t have high hopes, he put his son in public school instead.

During his first year at public school, one teacher took a special

interest in the boy and often made a point to praise him for his work, slowly raising his confidence. By the end of that year, he came home with a glowing, straight A report card. His father was apoplectic.

“You cheated,” Salim said, raising his hand to punish his son. The next morning, his parents confronted the teacher. “My son doesn’t get these types of grades. He must be cheating.”

“No, he’s not cheating. I can assure you of that.”

“Then what kind of school are you running here, where a boy like Souhel can get these kinds of grades?”

The teacher paused before speaking again. “Did you ever think that you might actually have a smart son? I think you need to believe in him.”

Dr. Najjar would eventually graduate at the top of his class in medical school and immigrate to the United States, where he not only became an esteemed neurologist but also an epileptologist and neuropathologist. His own story carried with it a moral that applied to all of his patients: he was determined never to give up on any of them.

Now, in my hospital room, he crouched down beside me and said, “I will do my best to help you. I will not hurt you.” I didn’t say anything, looking emotionless. “Okay, let’s begin. What is your name?”

A considerable pause. “Su . . . sa . . . nnn . . . aaah.”

“What is the year?”

Pause. “2009.” He wrote down “monosyllabic.”

“What is the month?”

Pause. “Appril. Appril.” I struggled here. He wrote “indifferent,” meaning apathetic.

“What is the date?”

I looked forward, showing no emotion, saying nothing, not blinking. He wrote down “paucity of eye blinking.” I didn’t have an answer for him on this one.

“Who is the president?”

Pause. I raised my hand rigidly in front of me. He wrote “stiff-bodied” on his chart. “Wha?” No emotions. Nothing.

“Who is the president?” He noted “lack of attention span.”

“O, Obama.” He wrote, “low tone, monotonous with a substantial lisp.” I was not able to control the movements of my tongue. He removed a few tools from his white lab coat. Using a reflex hammer, he tapped on my kneecaps, which did not jerk forward the way they should. He shined a light into my eyes, noting that my pupils were not properly constricting.

“Okay, now, touch your nose with this hand,” he said, touching my right arm. Stiffly and robotically, I raised my arm and in several slow-moving motions, reached my hand to my face, narrowly missing my nose.

Hellishly catatonic,

he thought.

“Okay,” he said, testing my ability to do a two-step command. “Touch your left ear with your left hand.” He grazed my left arm to indicate right from left, doubting I could figure it out myself. I didn’t move or react; instead, I just sighed. He told me to forget about this step and moved on to another. “I’d like you to get out of bed and walk for me.” I dangled my feet over the edge and slid haltingly onto the floor. He took my arm and helped me stand. “Will you walk a straight line, one foot after the other?” he asked.

Taking a minute to think it through, I began walking in short spurts but with delays between steps. I angled toward my left side—Najjar noticed I was showing signs of ataxia, a lack of coordinated movement. I walked and talked like many of his late-stage Alzheimer’s patients, who have lost their capacities to speak and appropriately interact with their environments, save for short bursts of uncontrolled, abnormal movements. They do not smile, hardly blink, and remain unnaturally rigid, with one foot firmly planted in another world. And then he had an idea: the clock test. Although developed in the mid-1950s, the clock test had been entered into the American Psychiatric Association’s

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

only in 1987

and is used to diagnose problem areas of the brain in Alzheimer’s, stroke, and dementia patients.

33

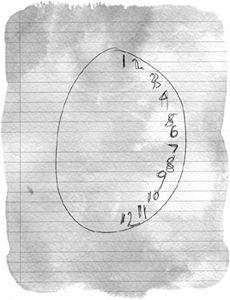

Dr. Najjar handed me a blank sheet of paper that he had ripped out of his notebook and said, “Would you draw a clock for me and fill in all the numbers, 1 through 12?” I looked up at him with confusion. “As you remember it, Susannah. It does not have to be perfect.”

I looked at the doctor and then back down at the paper. I held the pen loosely in my right hand, as if it were a foreign object. I first drew a circle, but it was lopsided and the lines were too squiggly. I asked for another sheet. He tore another out for me, and I tried again. This time a circle took shape. Because circle drawing is a type of procedural memory (one that was also still present in the famous amnesiac patient H.M.), that is, an overlearned practice, like tying shoes, patients have done it so many times before that they rarely get it wrong, so it didn’t surprise him that I drew it with relative ease the second time. I outlined the circle once, twice, and then three times, an act called perseverative dysgraphia, a disorder in which a patient draws and redraws lines or letters. Dr. Najjar waited expectantly for the numbers.

“Now draw numbers on the clock.”

I hesitated. He could see me straining to remember what a clock face looked like. I hunched over the paper and began to write. Methodically I wrote the numbers. Often I would get stuck on a number and draw it several times: more perseverative dysgraphia.

After a moment, Dr. Najjar looked down at the page and nearly applauded. I had squished all the numbers, 1 through 12, onto the right-hand side of the circle; it was a perfect specimen, with the twelve o’clock landing almost exactly where the six o’clock should have been.

Re-creation of my clock drawing.

Dr. Najjar, beaming, grabbed the paper, showed it to my parents, and explained what this meant. They gasped with a combination of terror and hope. This was finally the clue that everyone was searching for. It didn’t involve fancy machinery or invasive tests; it required only paper and pen. It had given Dr. Najjar concrete evidence that the right hemisphere of my brain was inflamed.

The healthy brain enables vision through a complex process involving both hemispheres.

34

First, certain receptors are activated in the retina, and information passes through the eye and visual pathways until it reaches the primary visual cortex, located at the back of the brain, where it becomes one single perception, which the parietal and temporal lobes then process. The parietal lobes provide the person with the “where and when” of the image, situating us in time and space. The temporal lobe supplies the “who, what, and why,” governing our ability to recognize names, feelings, and memories. But in a broken brain, where one hemisphere isn’t working properly and the flow of information is obstructed, the visual world becomes lopsided.

Because the brain works contralaterally, meaning that the right hemisphere is responsible for the left field of vision and the left

hemisphere is responsible for the right field of vision, my clock drawing, which had numbers drawn on only the right side, showed that the right hemisphere—responsible for seeing the left side of that clock—was compromised, to say the least. Visual neglect, however, is not blindness. The retinas are still active and still sending information to the visual cortex; it’s just that the information is not being processed accurately in a way that enables us to “see” an image. A more accurate term for this, some doctors say, is visual indifference:

35

the brain simply does not care about what’s going on in the left side of its universe.

The clock test also helped explain another aspect of my illness that had largely been ignored: the numbness on the left side of my body that had since become a long-lost nonissue. The parietal lobe is also involved in sensation, and malfunction there could result in a feeling of numbness.

This single clock-drawing test answered so much: in addition to the numbness on the left side, it explained the paranoia, the seizures, and the hallucinations. It might even account for my imaginary bedbugs, since my “bites” occurred on my left arm. Ruling out schizoaffective disorder, postictal psychosis, and viral encephalitis and taking into account the high white blood cells in the lumbar puncture, Dr. Najjar had an epiphany: the inflammation was almost certainly the result of an autoimmune reaction, caused by my own body. But what type of autoimmune disease? There had been an autoimmune panel, which tests for only a small fraction of the hundred or so known autoimmune diseases, that had come back negative, so it couldn’t be one of those. Dr. Najjar then recalled a series of cases in the recent medical literature about a rare autoimmune disease that affects mostly young women that had come out of the University of Pennsylvania. Could that be it?